A recent study in JAMA Neurology shows a significant link between the amount of amyloid-beta in the brain and the risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a harbinger of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

A recent study in JAMA Neurology shows a significant link between the amount of amyloid-beta in the brain and the risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a harbinger of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

The authors of the study, entitled "Association of Elevated Amyloid Levels With Cognition and Biomarkers in Cognitively Normal People From the Community," noted that this was the first research to be performed using "normal" study subjects randomly selected from the at-large population of older individuals.

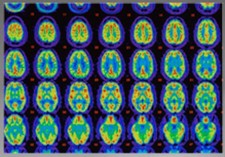

Researchers from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester MN, led by Ronald C. Petersen, PhD, MD, used specialized positron-emission tomography, or PET, scans to quantitate the volume of amyloid deposition in the brains of 564 subjects who were cognitively normal at baseline.

Amyloid is a proteinaceous material characteristic of neurodegeneration. The scans used specialized tracer materials, which bind to amyloid and emit detectable coloring.

Generally, older people have a 1-2 percent risk of developing MCI per year. Previous studies (done on selected populations with higher average risk, however) have shown a rate of progression to MCI of almost 10 percent, per year, among those with elevated beta-amyloid levels detected on PET scan. Among MCI patients, the risk of deterioration to AD is between 15 percent and 20 percent annually.

The mean age of the group was 78, and they were followed, on average for two and a half years. At baseline, participants underwent MRI scanning; a form of PET scanning to assess glucose metabolism which reflects a general index of brain activity and overall function; and a special amyloid-specific PET scan using Pittsburgh compound B (PET-PiB) scanning to assess amyloid levels.

In the current study, at baseline, 179 individuals, or 32 percent, had elevated amyloid levels, which were associated with poorer cognition and slower glucose metabolism. At follow-up, it was found that individuals with elevated amyloid levels at baseline had a greater rate of cognitive decline in all domains.

They also had greater rates of amyloid accumulation (1.6 percent per year) and other deleterious anatomical brain changes. During a median follow-up period of 2.5 years, 84 individuals progressed clinically to mild cognitive impairment, and four progressed to dementia. This represented an almost three-fold increased risk of MCI compared to those without amyloid brain accumulation.

"We found that individuals in the general population who are amyloid positive but cognitively normal do have an increased risk of progresAlsing to cognitive impairment, said Dr. Petersen, as told to Medscape Medical News. He added that it was premature to make any clinical recommendations on the basis of these findings.

Such testing could be useful in patients who have MCI to identify those who might have a quicker decline. They should not be used in cognitively normal people at present. We do not know what to tell them if a scan shows elevated amyloid. We don't know the natural course. We need to watch these data unveil themselves over the next few years.

But the situation would be different if a preventive agent was made available. Then a reliable diagnostic test or even a test showing an increased risk would be very valuable.

"At present, all we can recommend is that people pay attention to their lifestyle engage in aerobic exercise, stay intellectually active, eat a healthy diet, stay involved in social relationships," Dr. Petersen added. "I know this sounds a bit 'Mom and Pop,' but it will likely be effective."

For another viewpoint on the status and future of AD testing, see my op-ed in Forbes, co-written with Dr. Henry Miller: Steady Progress On America's Most Terrifying Epidemic: Alzheimer's Disease.