What's in a name?

When it comes to encouraging diners to eat healthier – by consuming more vegetables – a new study says how they are described is more important than we might have otherwise thought.

In what basically amounts to an exercise that combines psychology, marketing and food salesmanship in equal parts, researchers learned that if you jazz up the names of vegetable dishes more diners will eat them.

Equally interesting was that giving them healthy-sounding descriptions discouraged consumption, because people perceive those dishes to be less enjoyable and less tasty. Additionally, making vegetable dishes sound more fattening – even when they're not – got consumers to eat more of them, and eat them more often.

Food descriptions that included terminology such as "reduced-sodium," "sugar-free," "cholesterol-free" and "light 'n' low-carb" by-and-large repelled consumers from selecting the offering. Meanwhile, diners were drawn to dishes described with terms like "rich buttery," "tangy ginger," "slow-roasted" and "twisted citrus-glazed."

“We have this intuition to describe healthy foods in terms of their health attributes," said the lead author Bradley Turnwald, a graduate psychology student, "but this study suggests that emphasizing health can actually discourage diners from choosing healthy options.”

Here's how the study, which was published as a research letter this week in JAMA Internal Medicine, was conducted. Researchers at Stanford University used the school's cafeteria as their lunchtime laboratory – obtaining the approval of the university's institutional review board beforehand – for 46 days last fall. Of the 27,933 total diners served, nearly 8,300 – or 30 percent – selected the vegetable offering. Roughly 53 percent of all diners were undergraduate students, 33 percent were grad students and 15 percent were categorized as "staff/other."

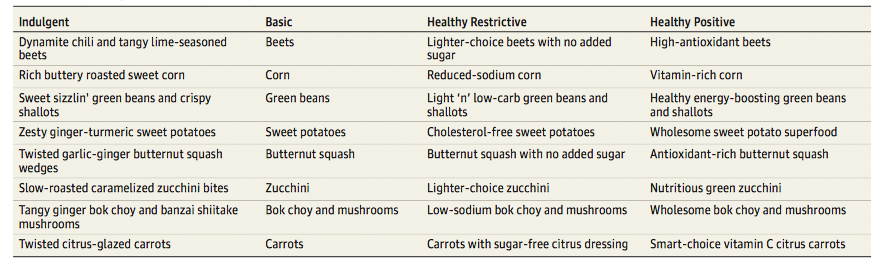

In the research letter the authors wrote that, "Each day, one featured vegetable was randomly labeled in 1 of 4 ways: basic, healthy restrictive, healthy positive, or indulgent," (see adjacent table; credit authors Bradley Turnwald, MS, et al). "No changes were made to how the vegetables were prepared or served. Each day research assistants discretely recorded the number of diners selecting the vegetable and weighed the mass of vegetables taken from the serving bowl."

And in the final analysis, by a large margin lunchtime eaters went for the food that sounded better – even when it was prepared exactly the same way, and when offered on another day with a less appealing description.

"[L]abeling vegetables indulgently resulted in 25% more people selecting the vegetable than in the basic condition," the authors wrote, "35% more people than in the healthy positive condition," and "41% more people than in the healthy restrictive condition."

As for volume of dishes eaten, "vegetables with indulgent labeling were consumed 16 percent more than those labeled healthy positive, 23 percent more than basic and 33 more than healthy restrictive."

While the results don't gauge the choices of all demographic groups, all told they are certainly encouraging. In addition, this research includes participants that are mostly young adults, whose eating habits are still taking shape. And if making healthy food more attractive can be done simply using better salesmanship, that sounds more than a worthwhile tradeoff, and an easy adjustment at that.