Remember when the term "designer drug" was used in the 1980s? One of the drugs included in that group was called 3-methylfentanyl, aka, mefentanyl. Although not widely used, it killed groups of people who tried it. Fast forward 4 decades and it's now one of the 30 fentanyl analogs that are responsible for the fentanyl crisis. And it's also one of the worst. What a difference a methyl group can make.

In a sense, we are fortunate. That is if you can call 100,000 overdose deaths per year, mostly due to fentanyl, fortunate. I say this because things could be far worse; the addition of just one little methyl group and fentanyl becomes mefentanyl aka 3-methylfentanyl – an entirely different beast. It's also called "China White." (1)

If you look at the chemical structures of the two, you might conclude that they are more or less the same drug. They sure look alike (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fentanyl (L) and Mefentanyl (R) differ by only one methyl group (arrow)

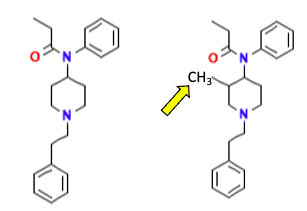

But, as any competent medicinal chemist will tell you, the absence or presence of one carbon atom, even within a much larger molecule, can make quite a difference. Here are two other examples (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The impact of a single methyl group on biological activity. (Right) Benzene is a known carcinogen (and something organic chemists avoid if possible), while toluene (used as a substitute for benzene) is not. (Left) Normorphine – morphine minus the methyl group of morphine has little or no analgesic activity.

Some facts about mefentanyl

It is more potent than fentanyl and more dangerous. How much more so? A lot. Consider the following.

- Binding

Binding experiments can only tell you so much about a drug, but here's one that tells you plenty. A 1991 study published in the journal Neuropharmacology examined mefentanyl's crazy-high potency (more on that later.) The NIH researchers found that when mefentanyl was incubated with opioid receptors and then the drug washed off (a typical procedure for binding experiments), some of the mefentanyl stayed behind. This is not typical; fentanyl, as well as several other analogs, washed off the receptors. The authors used the term "pseudo-irreversible inhibition" and speculated that this "might contribute to the extraordinary potency" of the drug. Although binding experiments may or may not correlate with the strength of an opioid, it seems likely in this case.

- Most antibody detection methods for fentanyl fail for mefentanyl

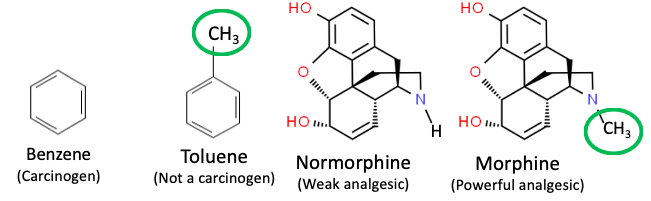

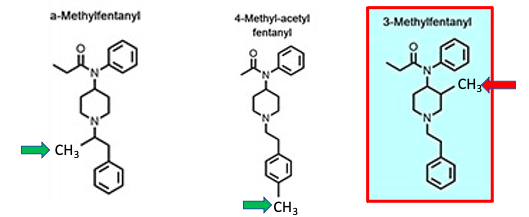

It's a damn good thing that mefentanyl isn't one of the common fentanyls pouring into this country. Both because of its potency and as a recent paper in the Journal of Analytical Toxicology concluded, antibody-based detection methods (such as the standard (2) fentanyl test strips) do not effectively detect mefentanyl – something that would not be intuitively obvious to a chemist. This is more than a bit strange. Some highlights from the paper demonstrate the strangeness. For example, most analogs that differ only by the group attached to the amide carbonyl (green arrow) were recognized by the antibodies that detect fentanyl (Figure 3). (Acetylfentanyl, second from the left, is one of the common fentanyl analogs circulating in the US. It is similar to fentanyl but weaker.)

Figure 3. Fentanyl analogs detected by the fentanyl immunoassay. The green arrows indicate the difference in the acyl groups.Source Journal of Analytical Toxicology

But this trend does not necessarily hold up for other fentanyl analogs that differ by the addition of one methyl group. The fentanyl strips detect both alpha-methylfentanyl (Left) and 4-methyl-acetyl fentanyl, (2) but 3-methylfentanyl (mefentanyl) is only "modestly detected." This is why we are "fortunate." Imagine if a much more potent analog of fentanyl widely circulating in the US with no way to detect it preemptively. Nightmare. (3)

Source Journal of Analytical Toxicology

How much stronger is mefentanyl?

Unfortunately, this question has no simple answer because the drug consists of four different 3-methylfentanyl isomers, each with a different profile. Because I like most of you (and am not in the mood to hang myself), I will not segue into a discussion of stereochemistry – a truly hideous but essential facet of organic chemistry. You're just going to have to assume that I know what I'm talking about – perhaps a stretch – and accept that there are four of the SOBs that make up what is called 3-methylfentanyl. But their real chemical names are all different, so I'm just going to focus on the most potent one, which has the unfortunate name of N-[(3R,4S)-3-Methyl-1-(2-phenylethyl)-4-piperidinyl]-N-phenylpropanamide, aka cis-(+)-3-methylfentanyl. Its potency is scary [emphasis added].

The median effective dose (ED50) of cis-(+)-2, which is the most potent among the four isomers, was found to be 0.00767 mg/kg (in mice, ip., hot plate) with 2600 times as potent as morphine (4)

Wang ZX, Zhu YC, Chen XJ, Ji RY. [Stereoisomers of 3-methylfentanyl: synthesis, absolute configuration and analgesic activity]. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 1993;28(12):905-10. Chinese. PMID: 8030414.

Oh, my. Since the potency of fentanyl is routinely given as "50-100 times stronger than morphine," let's call it 75-times. This would make mefentanyl something like 35-times more potent than fentanyl. This puts mefentanyl close to the potency of carfentanil – the elephant tranquilizer.

These numbers are consistent with the relative blood levels of the drugs measured in overdose victims. A 2020 review reported that the mean blood concentration in people who died from fentanyl was 24 ng/mL while the concentration of mefentanyl in three overdose victims was 0.5 ng/mL, suggesting a ~50-fold difference in potency between the two drugs.

Let's split the difference and assume that mefentanyl is 40-fold more potent. Since a lethal dose of fentanyl is 2 mg this would make the lethal dose of 3-methylfentanyl 0.05 mg (50 micrograms). You cannot possibly see .05 mg of anything. Want proof? A grain of salt weighs 0.3 mg. If you're Superman maybe you can see one-sixth of a grain of salt.

Or not...

Mefentanyl and Chechen terrorists?

Perhaps you remember the 2002 hostage crisis in Moscow where Chechen terrorists stormed a theater and held 800 people – a full house – hostage, demanding an independent Chechnya. Vladamir Putin's handling of the hostage situation was not subtle. Russian special forces pumped a really powerful narcotic gas into the theater, which certainly ended the standoff but left 120 hostages dead. The Russians were not forthcoming about what drug they used, leading to speculation at the time that it was mefentanyl. Some history books say it was fentanyl. Both are wrong. An analysis of two clothing samples and one urine sample of survivors showed a mixture of carfentanil and remifentanil. This makes sense since both drugs have medical uses and were commercially available, while mefentanyl, which was referred to as a "designer drug" at that time, has no approved medical use.

Bottom line

I have written before that the combination of chemistry and biology to understand the behavior of drugs is endlessly fascinating. Seemingly small changes in structure can result in substantial differences in drug properties. The comparison of fentanyl and mefentanyl is a quintessential example of structure-activity relationships – the cornerstone of drug discovery.

NOTES:

(1) Other drugs are also referred to as "China White," including heroin and fentanyl. And a Benjamin Moore paint color.

(2) 4-Methylfentanyl, the direct comparator to fentanyl, was not one of the analogs tested, so I used the 4-methyl-acetylfentanyl instead.

(3) A new product from an organization called Dance Safe claims that its test strips do detect 3-methylfentanyl. Of course, thanks to our idiotic drug laws, fentanyl test strips are illegal. See Fentanyl Test Strips Are Illegal. This Is Obscene.

(4) The paper reads "(ED50) of cis-(+)-2," but it clearly refers to 3-methyl fentanyl. I don't know if this is a typo error or the authors are using a different numbering system.