Although COVID-19 is giving us a temporary respite, influenza in humans and animals remains a serious threat. Its deadly H5N1 strain is spreading geographically and in more species of mammals, making the emergence of a pandemic strain more likely. We need to prepare.

There are signs of a mid-summer surge in COVID-19 cases, particularly in the South and West, that have some experts concerned. But even the very risk-averse expect it to be small relative to past years.

The bigger issue is whether we are letting down our defenses against other viruses as the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic fades from the headlines? Although the more than 1.1 million deaths and hundreds of thousands of cases of Americans with lingering long COVID are a grim reminder of what we have endured, most people have neglected to get the most recent vaccine booster, stopped masking, and instead have turned their attention to sun and fun.

However, those of us who study infectious diseases are acutely aware that coronaviruses, one of which, SARS-CoV-2, is the etiologic agent of COVID-19, are zoonotic agents – that is, they can spread infection between people and animals. These infections can be caused by viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi. Some infections can be severe and life-threatening, such as rabies, MERS, anthrax, bubonic plague, and SARS-CoV-2, while others are milder.

The zoonotic nature of COVID transmissibility has been particularly unsettling, as we initially found the virus in bats and minks, and then in pets and later, in local deer populations. Thus, not only do we have to be concerned about the human population, but our animals as well.

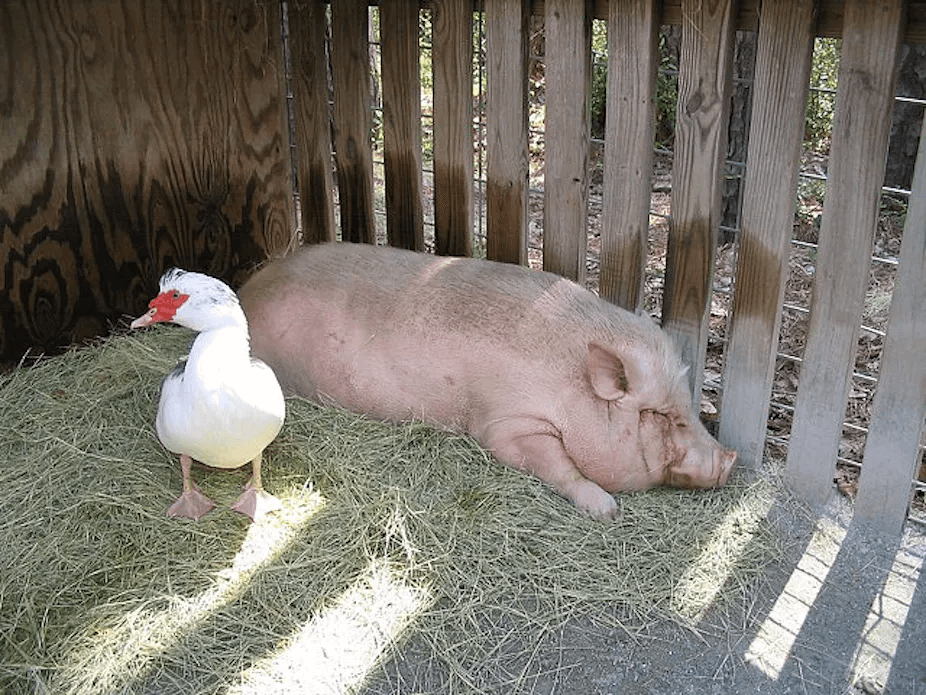

We remain vulnerable to outbreaks, and even pandemics, of zoonotic diseases. Last week, the CDC reported the first two U.S. human infections of the year with swine flu viruses. "These human infections were caused by two different types of flu viruses that normally spread among pigs, and they occurred in two people who attended different agricultural fairs in Michigan and had exposure to pigs." There is no indication of human-to-human spread.

A greater concern among epidemiologists and infectious disease experts is that a serious outbreak could be caused by a new strain of an old foe, a variant of the N5H1 strain of avian influenza virus. Recently, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, the World Health Organization (WHO), and the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) strongly urged that nations collaborate to prepare for this latest threat to our lives and livelihoods.

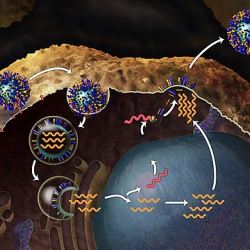

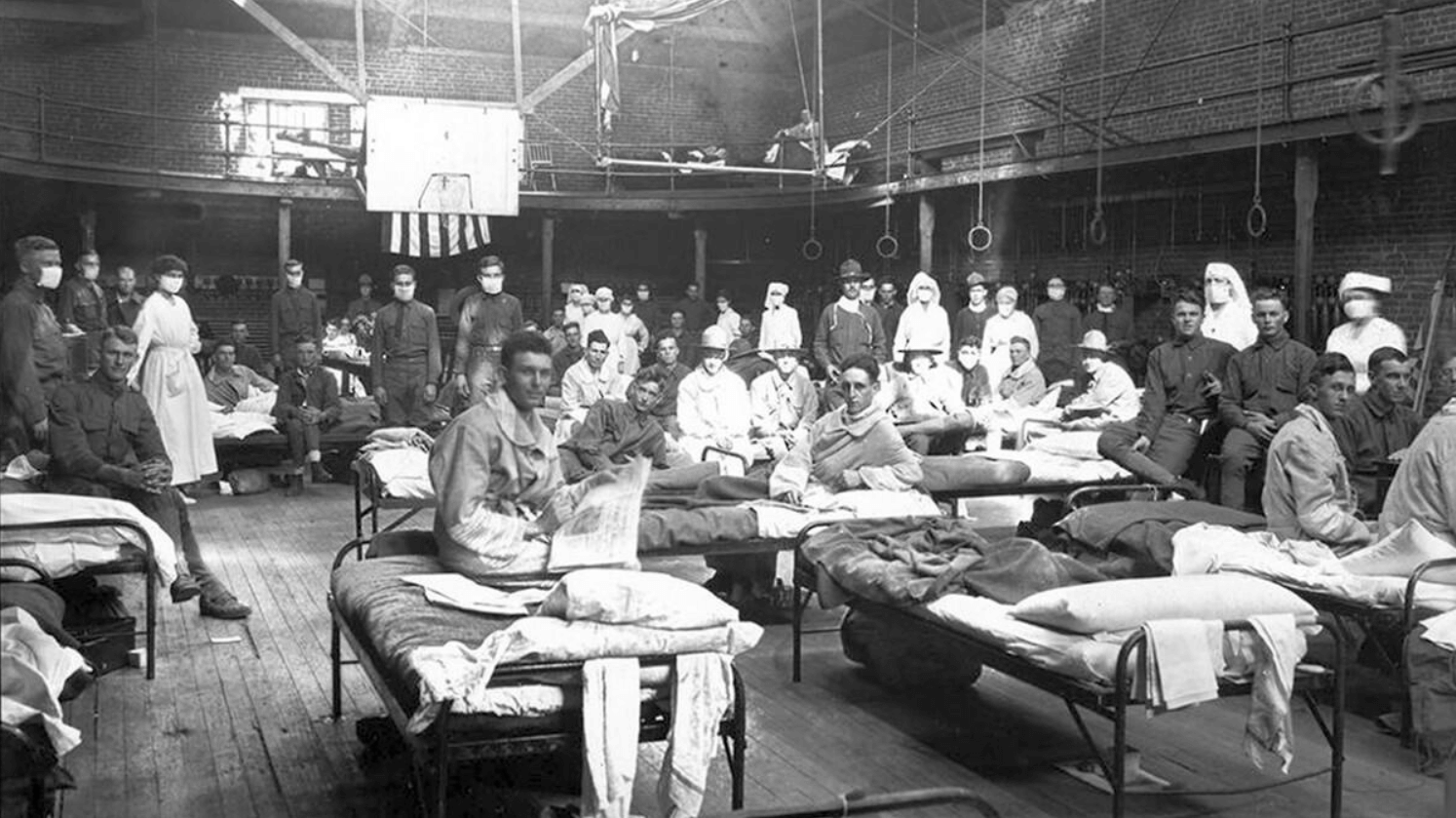

Avian influenza, or “bird flu,” traditionally spreads among both wild and domestic bird populations. Influenza virus strains such as bird flu and swine flu are able to co-infect animals, so they can mix and match segments of genetic material (RNA) to create new and more infectious and/or more virulent virus strains. Both avian and swine flu have been the source of nasty pandemics, with the 1918-19 Spanish flu (H1N1) perhaps being the most notorious.

Influenza strains are designated by the unique epitopes found on the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) proteins, which are found on their surface and assist with their entry and exit into and from cells, analogous to the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. A new H5N1 strain might then have an enhanced ability to jump from birds to mammals, raising concerns that it might be just a matter of time before the virus infects humans. The greatest concern is that the virus would then become capable of human-to-human transmission.

How does this happen? There are two ways that flu viruses commonly evolve. One is called “antigenic drift,” the result of small genetic mutations that give rise to changes in the surface proteins of the virus, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). Those mutations usually produce viruses that are closely related to one another, which means that antibodies elicited by exposure to one flu virus will likely recognize other viruses that arose from antigenic drift.

Another, more drastic type of change is called “antigenic shift,” a major genetic change that gives rise to new, significantly different HA and/or NA proteins in flu viruses that enables them to infect humans. This is more likely to occur when there is co-infection by different viruses — say, human and avian flu viruses simultaneously infecting an animal host — and there is reassortment of RNAs, giving rise to new viruses that are different enough that most people do not have immunity to them.

Such a “shift” occurred in the spring of 2009, when an H1N1 virus with genes from viruses originating from North American swine, Eurasian swine, humans, and birds emerged, infecting people, spreading quickly, and causing a pandemic.

Based on reports from across the world, there is reason to be concerned that we could be in store for a shift event. In 2022, 67 different countries reported H5N1 flu in both domestic and wild bird populations, with over 130 million poultry lost from virus infection or from culling performed to stop virus spread. The 2022 outbreak was the deadliest on record in the U.S., affecting nearly every state and forcing culls of more than 50 million birds. (That’s the main reason that poultry and egg prices spiked last year.)

Equally if not more disturbing are recent reports of H5N1 among mammals in 10 different countries since 2022. This is certainly an underestimate, as outbreaks of avian flu in mammals would be unexpected and, therefore, underreported. Over two dozen species of mammals are known to harbor the virus, including cats and dogs. The extent of this spread makes it inevitable that the virus will reach humans.

Avian flu kills almost all the birds it infects, and globally, from January 2003 to May 2023, 876 cases of human infection with avian influenza A(H5N1) virus were reported from 23 countries. Of those cases, 458 were fatal (case fatality rate of 52%). During the past 18 months, a handful of human cases — but, as yet no human-to-human transmission — have been reported. Infection has been associated with severe symptoms and some deaths.

Credit: Mark Pilgrin/Flickr

Like our initial encounter with COVID-19, we are ill-prepared for this “pandemic-in-waiting.” If a new H5N1 variant were highly transmissible from human-to-human, once again we could quickly get behind the curves of infections, hospitalizations, and deaths.

The U.S. response to the COVID pandemic was hindered by a deluge of misinformation and disinformation that emanated from Russia’s propaganda apparatus and its U.S.-based “useful idiots,” including a handful of healthcare professionals and even one presidential wannabe (Robert F. Kennedy, Jr.). It has made communication about the benefits of vaccines, masks, and other interventions extremely challenging, and the numbers of vaccinations against other preventable diseases, such as measles, are down since the emergence of SARS-CoV-2.

There is plenty to be done to prepare. Our immunity against H5N1 is likely to be minimal, so new vaccines are urgently needed. Public health leaders, animal health scientists, and vaccine manufacturers should already be communicating with one other about the risk. Exposure to sick animals should be reported. We need an infrastructure for animal surveillance, but we are still underperforming on this, even after all that we have learned from COVID-19. Emerging variants of H5N1 need to be identified and sequenced and the sequences uploaded onto easily accessible databases.

The Biden Administration has just created an Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response Policy (OPPR) in the Executive Office of the President, “charged with leading, coordinating, and implementing actions related to preparedness for, and response to, known and unknown biological threats or pathogens that could lead to a pandemic or to significant public health-related disruptions in the United States.” It will “take over the duties of the current COVID-19 Response Team and Mpox Team at the White House and will continue to coordinate and develop policies and priorities related to pandemic preparedness and response.” Many of President Biden’s public health appointments have been barely mediocre on their best days, however, so we are skeptical.

We need to be vigilant about the threat of new influenza viruses. Our population and livestock, and even our pets, might soon be in jeopardy.

Kathleen L. Hefferon is an instructor in microbiology at Cornell University. Find Kathleen on Twitter @KHefferon Henry I. Miller, a physician and molecular biologist, is the Glenn Swogger Distinguished Fellow at the American Council on Science and Health. He was the founding director of the FDA’s Office of Biotechnology. Find Henry on Twitter @henryimiller