Here's the premise: social justice and equitable care increasingly require that those individuals providing your healthcare look like you and share your lived experience. To that end, medical schools have fashioned (or refashioned) their mission statements to explicitly call for diversity in their student bodies. But as a new study shows, words and intentions are not sufficient.

The study, published in JAMA Open Network, looked at the mission statement of 60 new medical schools established since 2000

“Mission statements have often been viewed as a school’s public commitment to societal needs. They highlight the purpose and priorities of an institution and can influence resource allocation. … The purpose of this study was to investigate the association between the prevalence of diversity language, including terms like diversity and inclusion, in the mission statements … and the racial and ethnic composition of their student bodies.”

Simply put, do the deeds match the words? Let’s just save some time; the answer is maybe, it depends.

Of the 60 medical schools:

- 55% included diversity language, 42% referred to the diversity of their students and the future workforce, 81% referred to the diversity of patient populations

- The percentage of schools with diversity language did not change over the 20-year period.

- “Overall, there were no significant differences in the racial and ethnic composition of student bodies in schools whose mission statements referenced diversity compared with those that did not.”

- “These numbers [enrolled students characterized as American Indian or Alaska Native, Black or African American, and Hispanic or Latinx] fall well below the groups’ representation in the overall US population.”

Why might this be?

The researchers offer the obligatory possibilities:

- Institutional racism gets a nod – “excluded racial and ethnic groups cannot just be attributed to entrenched institutional policies and power structures.” [emphasis added]

- “Overreliance on grade point averages and standardized test scores”

- “Lack of faculty diversity”

- “Insufficient organizational resources and commitment to increasing diversity.”

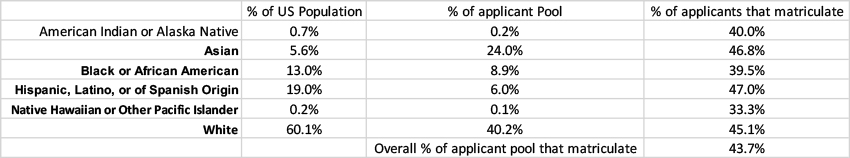

The American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) does post the racial mix of the applicant pool, those accepted, and those that enroll. I have abstracted some of the 2023 data

One metric that jumps out is that, except for Asians, the pecentage of applicants applying to US medical schools is below their percentage in the general population. The second metric to note is that the percentages of the applicant pool that attend medical school are almost identical to the racial percentages applying. A significant issue in reaching diversity is that many underrepresented groups simply are not applying. This suggests that fewer individuals, in general, may be choosing medical careers. Of course, this could also be attributed to a lack of role models or other social disparities. The beauty of these data dots is that you can weave them into a pattern of your liking.

Looking into the AAMC data more deeply uncovers other “disparities.” For example, the categorization as Asian has 13 subdivisions, including Chinese, Japanese, Indian, Cambodian, Pakistani, etc. While the overall acceptance rate is roughly 46%, medical schools take in fewer Bangladeshi and Cambodians than Chinese, Korean, Japanese or Indian. Does that reflect bias, racism, or disinterest in the field? One does not know; any discussion is more grounded in conjecture than fact.

Did the schools actually fail to achieve diversity? Certainly, that argument can be made when the comparator is the racial breakdown of the US population. But when you consider the admitted class of 2027, it does not, it simply reflects the racial breakdown of the applicant pool.

“Educational psychologists have described a flattening phenomenon whereby diversity is frequently discussed but seldom put into practice. Mission statements that contain diversity language may be reflecting this phenomenon and be aspirational but not operationalized.”

I prefer the same sentiment expressed by noted child psychologist Mary Poppins. These mission statements are “piecrust promises, easily made, and easily broken.”

Source: Diversity in Mission Statements and Among Students at US Medical Schools Accredited Since 2000 JAMA Network Open DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.46916 (