As High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza cases emerge in dairy cattle, transmission routes and the source of infection remain unclear. Before jumping to conclusions, what can science tell us?

“The ongoing spread of High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza (HPAI) in different regions of the world, alongside the recent detections of cases in cattle, is raising concerns within the international community…. In the last two years, an increasing number of H5N1 avian influenza cases have been reported in terrestrial and aquatic mammalians animals.

The recently reported detections of HPAI (High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza) in dairy cattle in the United States of … have raised concerns since such infections of cattle could indicate an increased risk of H5N1 viruses becoming better adapted to mammals, and potentially spilling over to humans and other livestock.”

– World Organization for Animal Health (WAOH)

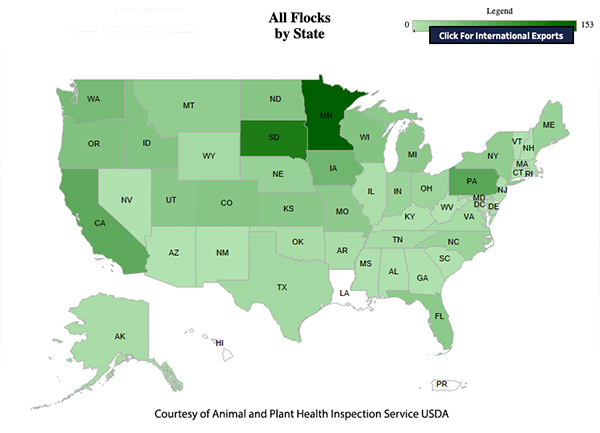

H5N1, the Avian Flu, is a growing problem for us. For the chickens, it has led to the culling of 85 million birds in an attempt to isolate cases. While the map shows that the most significant number of cases has been in the  upper mid-West, the 30-day map shows a concentration of cases in Texas, where those first cases involving dairy cows have occurred.

upper mid-West, the 30-day map shows a concentration of cases in Texas, where those first cases involving dairy cows have occurred.

“Over the last few months, we have had a whole series of diverse and varied mammals. It is worrying to see this extension to other species”

- Monique Eloit, Director WAOH

Before we add HPAI to our already free-floating anxieties, what can science tell us today about its transmission? For that, we can turn to a report in Science.

- The initial concern regarding dairy cattle was raised by the presence of dead cats on the dairy farms – presumably dying from drinking contaminated raw milk. The finding of the dead cats, dead wild birds, and an abnormally thickened milk raised suspicions, confirmed by culture.

- At this juncture, HPAI has only been found in a few dairy cows. Cultures have been positive in their milk but not in their blood or noses, so it appears to be “actively replicating” only in their udders. Before moving on, pasteurized milk is safe; the virus is killed in the pasteurization process. Raw milk remains problematic.

- How HPAI infected the cattle remains unclear. The USDA has identified a genetic signature for the virus infecting the cattle.

“It’s not a common [strain], but it’s very much a descendant of the viruses that have been dominating the flyways in the Pacific and the central flyways in the United States."

- Dr. Suelee Robbe Austerman of the USDA National Veterinary Services Laboratory

- While flyways suggest that a wild bird might be the source, another consideration is the movement of cattle around the Midwest in the spring. There is some evidence that “cows from infected farms in Texas appear to have moved the virus to farms in Idaho, Michigan, and Ohio.” Out of an abundance of caution, further transportation of cattle is discouraged, along with the continued segregation of bird flocks from other farm animals.

- The mode of transmission between cattle is equally unclear. Given the negative culture of cow noses, it has been suggested that the virus may be transmitted through milk droplets on inadequately cleaned milking machines or the clothing of dairy workers.

- These outbreaks are not limited to cattle. HPAI has been identified in seals in Antarctica and at least one polar bear in Alaska.

- Avian influenza can spread to humans through exposure to infected bird secretions or feces, leaving those in close contact with infected birds or contaminated areas at greater risk. Infection can be through an intermediate host, which is partly the concern regarding cattle. Influenza viruses can experience “antigenic shifts,” or reassortment, when two different influenza viruses co-infect a host and can “swap” their genes, creating a “new” virus. The first pandemic of this century involved “swine flu,” a combination of human, porcine, and avian influenzas.

High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza (HPAI) has taken an unexpected detour into the bovine world, but we should not worry that our morning latte might come with an unexpected side of avian flu. It adds another layer of complexity to our understanding of viral transmission and underscores the need for continued vigilance and research. It is wholly possible that HPAI will morph into a novel virus and we will once again be faced with a novel pandemic.

Source: Bird flu may be spreading in cows via milking and herd transport Science