A new paper from the Progressive Policy Institute, a Washington-based think tank, describes a “prescription escalator” to explain the apparent rising cost of pharmaceuticals. Let’s hit a few highlights

- List prices for brand drugs have risen 80% since 2014; another study suggested annual increases in list price by 9 to 15%

- Net prices that take into account all those opaque discounts and rebates rose 8.5% from 2016 to 2018. For comparison, the gross domestic product rose by 9.6%.

“That’s hardly the sign of an industry raking in big bucks.”

- Average household spending on prescription drugs fell by 11% between 2013 and 2018

- Average out-of-pocket spending on prescription drugs in “actually lower than countries such as Canada …”

- Overall the total average spending on healthcare only rises by about 2% per year. [1]

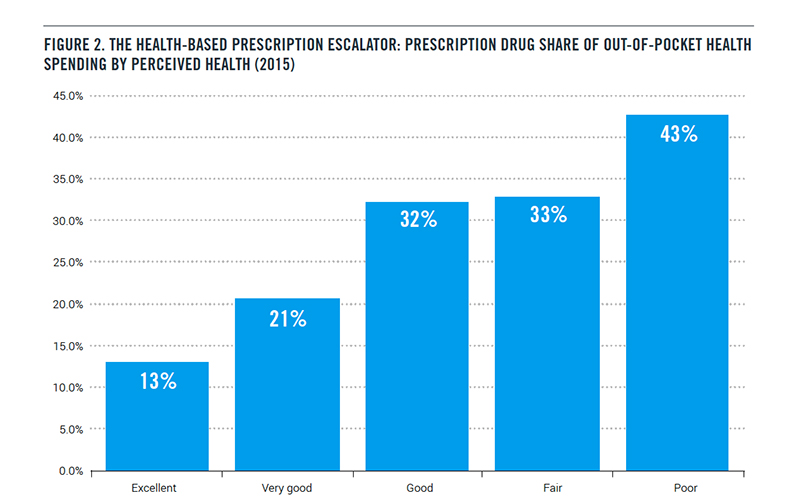

The careful reader will note that we are talking national averages, a calculation that includes the healthy and both the acutely and chronically ill. Averages can be deceiving. When out-of-pocket health spending is stratified by health, you begin to see the escalator metaphor come into view.

As it turns out, the escalation in spending is driven not by rising prices but rising utilization. Yes, we are prescribing more medications for the ill.

“… the average out-of-pocket cost per prescription is $15 for someone in excellent health, compared to $13 for someone in poor health. The big difference is that the person in poor health has 46 prescriptions [2], on average, compared to 3 prescriptions for the person in excellent health.”

Here is their calculation of the increasing out-of-pocket expenditures; prescription drugs are the second-lowest.

The Bottom Line

How can it be that average costs remain flat, while my costs are rising? That is, in part, due to differences in averages calculated across many different groups, and those for more specific groups. Simply put, the lack of prescriptions in the young balance out on average the increases for the elderly.

As we age, we develop more and more chronic illness, which is frequently treated with medications. The good news is that medical care improves our lives with medications. But, while the average out-of-pocket spending is rising, it rises far more slowly than the number of prescriptions being written – and the subsequent co-payments. Remember, co-payments are in place to give patients, well consumers, more skin in the game and chose their medications carefully. [3] More importantly, other forms of medical care rise more slowly. People can be treated with medications rather than surgery; outpatient care can replace hospitalization.

Another age-related factor adding to our perception of drug pricing is that our income declines as we get older. Even without a change in co-payments, a declining income would mean our percentage of medication spending would rise; and along with it would come a rising perception of cost.

“…even if drug reform efforts were successful and there were no more increases in drug costs, every individual would still face a 5.6% increase each year in drug spending as they got older. That would total 30% after five years, and 70% after ten years, across the board. These are enormous increases.”

This would suggest that rather than regulate drug prices, we can reduce the burden on the individual by capping out-of-pocket costs. Of course, those lost revenues would have to be absorbed or shifted by the overall drug market – manufacturers, distributors, pharmacy benefit managers, insurers, and retailers.

But the report does point out that all the smoke and mirrors about drug price transparency will have little effect. Patients are going to require more medications; a sedentary lifestyle with poor nutritional habits is almost a guarantee. And it will take several years, if not a generation, to turn those issues around. In the interim, if you want to control drug costs, let’s consider starting with the money we pay out of our pockets.

[1] Assuming prices remain stable.

[2] This figure includes both the prescription and refills, so that the real number of different medications is roughly 5-7 with the monthly or quarterly refills dramatically, and inaccurately, elevating the number of prescriptions.

[3] The study reports “that at $50 out-of-pocket for a prescription, new patient abandonment rates, both commercial and Medicare, are more than 25%. To put it another way, high out-of-pocket expenses are effective in deterring spending, which was their original policy purpose.”

Source: The Prescription Escalator: The Real Reason Why Americans Pay More for Drugs Each Year, Why They Are So Upset and What Can Be Done About It Progressive Policy Institute