The general belief is that COVID-19’s harms fall disproportionately upon the frail, as well as the classes and groups that often find themselves holding the short end of the stick: the poor and minorities. What makes these groups so susceptible? Let's take a look.

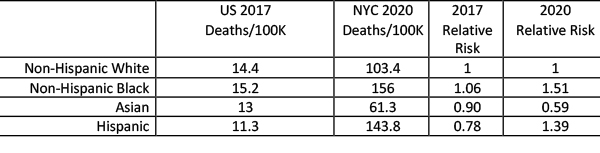

Let’s begin with a few facts, extrapolating as necessary. According to the CDC’s statistics on deaths in the United States, seasonal flu is an equal opportunity killer. In 2017, there were 55,672 deaths from the flu or pneumonia, 14.3 individuals per 100,000 population. The graph shows the CDC data accounting for different population sizes and further adjusted for age – some ethnic groups are younger in aggregate than others. I have left out Native Americans, whose numbers are the worst of all ethnicities. I have normalized the ethnic groups to give you a sense of their greater or lesser risk as compared to non-Hispanic Whites. The NY city COVID-19 related deaths are from New York’s Department of Health as of April 21st. I recognize that the numbers are debated, in flux, and a bit of apple vs. orange without gender stratification and incomplete reporting. So let us look at the big picture and not quibble about the exact numbers.

First, COVID-19 seems deadlier, 5 to 10, or more times more lethal. Second, Non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics have a higher risk of dying, in the range of 50% more. Asians, on the other hand, seem slightly “advantaged.”

The attack rate of COVID-19 is related to exposure, which will vary from region to region, but let us stay with the current epicenter New York City. Undoubtedly, the numbers will vary with other jurisdictions. There are at least three general reasons why we should see these outcome disparities, a genetic difference in these ethnicities, a higher burden of co-morbidities, or socio-demographic factors that impact health.

Genetics

While Asia was the source of the pandemic, and Asians have suffered loss of life, the relative risk of dying from seasonal flu for Asian-Americans was significantly less in 2017 and has dropped even more for COVID-19. In the short-term, co-morbidities and socio-demographic factors, including viral exposure as related to housing and work, change slowly if at all, suggesting that susceptibility to COVID-19 as with other diseases has a genetic component. While a genome-wide association study, GWAS, has yet to be performed, these studies rarely show broad genetic influences; a 2 or 3% genetic difference might be a ballpark figure. Of course, you have no choice in your genes, so it is not a modifiable risk factor.

Co-Morbidities

Here are the CDC’s 2017 top ten or so causes of death. It is a busy table, but a few things will stand out.

There is ethnic and gender diversity to our ills, the healthcare baggage we carry. Consider the deaths related to diabetes for indigenous people vs. Asians, or how cirrhosis, frequently an accompaniment to alcoholism is highest again among the indigenous people. Non-Hispanic Whites seem to have the cancer market, Non-Hispanic Blacks lead the way with heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, renal disease, hypertension, and death by assault. Hispanics don’t lead in any category, but again, look at cirrhosis, cerebrovascular disease, and assaults. Asians generally have the lowest numbers in any category. It is not a great leap of faith to understand how co-morbidities are both risk factors for COVID-19 and account for some of the disparities we see.

Socio-demographics

Some of these causes of death are lifestyle issues, like chronic lower respiratory diseases frequently found in smokers. Then there is assault. There is no special diet or pill that prevents being murdered, and I suppose if you are a criminal, it is a lifestyle choice. But for a majority of those cases, it is being in the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong people – socio-demographics.

Socio-demographic factors influence our exposures, not just to viruses, but to other health concerns, like pollutants. Individuals with public-facing and physical work, like drivers in our transport systems, especially taxis and “Ubers,” or factory workers, all work in environments with more significant exposures. Where, with whom and how many you live with also can increase or decrease exposure. Housing and population density both interact with employment in influencing exposure. Of course, education, opportunity, and income all play their roles too.

It should come as no surprise that COVID-19, like any health issue, shows disparities in who it attacks and their outcomes. Nor should it be a surprise that those at most risk for non-communicable diseases, like hypertension and heart disease, would get a greater share of this and other infectious diseases. Being vulnerable is a combination of genetics, lifestyle choices, and circumstances. We can exert some control over choices and circumstances, and perhaps we will do so as a result of the pandemic. I am fearful that we will once again not heed that message.

Source National Vital Statistics Reports Deaths: Final Data for 2017