On September 9th, President Biden announced his three-pronged vaccine mandate. The first two, addressing workers employed by the federal government and employees of hospitals and health care facilities funded by the federal government, are legal no-brainers such that even Libertarians aren’t putting up much of a fight. It’s the third prong that gives pause.

“All employers with 100+ employees to ensure their workers are vaccinated or tested weekly, and to pay for vaccination time.”

On its face, requiring businesses with more than 100 workers to require vaccination or testing is perfectly legal. Whether it would withstand legal challenge before a conservative Supreme Court is another matter. Whether it is prudent or warranted, i.e., necessary, is yet another question.

The mandate relies on a little-used provision of a 1970 law:

“The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 authorizes the secretary of the US Department of Labor to implement emergency rules, without the formal notice and comment process, when “employees are exposed to grave danger from exposure to substances or agents determined to be toxic or physically harmful or from new hazards.” [emphasis added]”

The emergency rule short circuits the regular rule-making process, which on average, takes seven years and nine months. And so, the Department of Labor, via its Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), is developing an emergency temporary standard, which is expected in the coming weeks. It is unclear when the rule will be implemented, but we can expect it to be challenged. My guess is that it would survive a temporary injunction to stay its immediate enforcement. The long-range resolution is anyone’s guess; I venture that will depend heavily on the state of COVID at the time of resolution – and the caliber of the arguments presented to the court.

The checkered past of the emergency temporary standard (ETS)

Some issues sure to be raised include whether the legal standards required to issue an ETS have been met – including whether COVID-19 presents a “grave danger” and whether the proposed rule is “necessary” to protect workers from that danger? Others question the constitutionality of the enabling legislation. Still others question whether emergency rules are allowable in these circumstances.

Can past litigation regarding ETS predict its future course?

Not many cases addressing the issue have been litigated. Only one (out of six challenges) preserved the ETS. But even where courts rejected OSHA’s alleged “power grab,” it was done on narrow grounds, validating OSHA’s power to act in such cases and essentially vindicating the constitutional validity of the provision.

The last decision on the matter came in 1984 when the Reagan administration tried to significantly reduce employee asbestos exposure via an emergency rule. That rule was eventually struck down in Asbestos Information Association v. OSHA. Nevertheless, the court held that OSHA had a good deal of leeway to decide when an emergency standard is warranted and whether certain levels of asbestos exposure constituted a grave danger. Only because OSHA did not consider less invasive alternatives, such as requiring respirators to filter out asbestos, and hence failed to address or satisfy (or explain away) the necessity requirement, did the court strike the rule.

I will address the “grave danger” and “necessity” requirements in other articles. Here I address the mandate’s constitutional aspects and ask whether its opponents raise their objections, as benign as they seem, in good faith? Are some voices opposing Biden’s proposal disingenuous? Do they reflect the true beliefs of the protestor? Or are they merely the rote repetition of a political ideology without due consideration, adequate knowledge, and critical thought - not just regarding public health law, but also relevant occupational health law.

The Loyal Opposition

Some at the Cato Institute and the George Mason School of Law are on the first line of attack – clearly without knowledge of occupational health law or practice. One argument they raise claims that ETS can only be enacted to protect against substances or agents, of which COVID, a virus, doesn’t qualify.

“A virus, like that at the root of the present pandemic, arguably doesn't qualify as a "substance or agent." These terms generally refer to chemicals, liquids or man-made dangers, not living things” Ilya Somin

Authors making such allegations should bone up on occupational health law and occupational (industrial) health practice before polluting the vaccine rhetoric, which is already too full of misinformation.

According to OSHA Law Sec. 1910. 1020:

“Toxic substance or harmful physical agent” means any chemical substance, biological agent (bacteria, virus, fungus, etc.), or physical stress (noise, heat, cold, vibration, repetitive motion, ionizing and non-ionizing radiation, hypo- or hyperbaric pressure, etc. …. that has yielded positive evidence of an acute or chronic health hazard in testing conducted by, or known to, the employer….”

Any student of occupational health who has read any standard Occupational Health and Safety textbook will tell you that:

“Substance covers a wide range of materials including single chemical compounds…. or synthetically produced substances and micro-organisms.” [emphasis added]

Those claiming that Congress exceeded its mandate in allowing OSHA such ETS rule-making powers are similarly ignorant of public health’s legal history. With the Quarantine Act of 1893, Congress removed exclusive quarantine jurisdiction of international transport from the states and imposed shared decision-making with the federal government. What happened when State and Federal Governments clash? Shortly after the Act’s enactment, the Supreme Court [1] ruled that the Federal Government had the last word, sanctioning the Congressional power-grab and overturning the time-honored premise that States ruled in all matters of public health.

Of more significance, the 51-year-old provision has not been challenged on constitutional grounds before – why now?

In June, OSHA implemented an ETS requiring stricter protocols for personal protective equipment (PPE) against COVID-19 in healthcare settings, a rule championed by labor unions. One current challenge to that rule, pending in the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, is that the rule didn’t go far enough! As to whether an emergency rule is the proper way to proceed - in contrast to the vaccine mandate, which is opposed by labor, this case is opposed by employers!

Is there a constitutional right to work that the mandate contravenes?

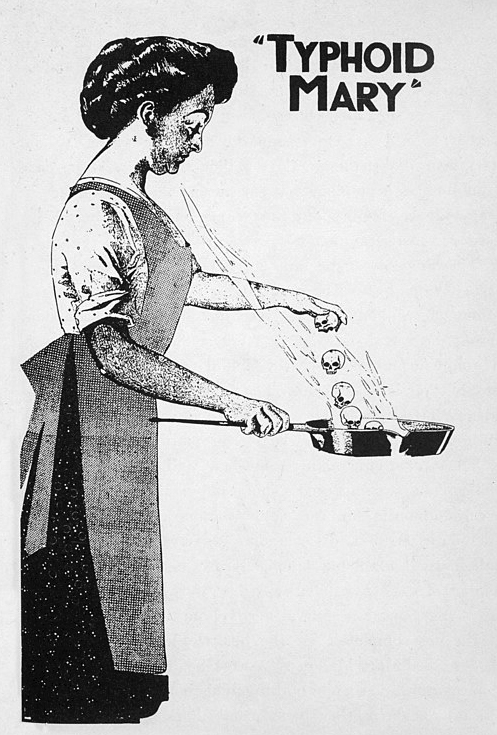

Short answer: No. Just ask Typhoid Mary.

Typhoid Mary, aka Mary Malone, was the Irish-born cook believed to have infected 53 people with typhoid fever during her tenure as a cook at ten different locations), killing three. Some say she seeded the NY typhoid epidemic of 1907, which infected 3000 people. Once public health officials proved she was the cause, she was arrested as a public health threat under the municipal charter of New York City and involuntarily quarantined, aka incarcerated, at Riverside Hospital on North Border Island.

Typhoid Mary, aka Mary Malone, was the Irish-born cook believed to have infected 53 people with typhoid fever during her tenure as a cook at ten different locations), killing three. Some say she seeded the NY typhoid epidemic of 1907, which infected 3000 people. Once public health officials proved she was the cause, she was arrested as a public health threat under the municipal charter of New York City and involuntarily quarantined, aka incarcerated, at Riverside Hospital on North Border Island.

Malone spent two years there before an “enlightened” health commissioner vowed to free her and assist with finding suitable employment as a domestic - but not as a cook. But Ms. Malone had no intention of complying. Hired under the pseudonym of Mary Brown, she secured work as a cook at Sloane Maternity in Manhattan, where she contaminated, in three months, at least 25 people, doctors, nurses, and staff. Eventually, she was sent back to Riverside Hospital, confined for the next 23 years.

People complained that Ms. Malone’s rights were violated, that the quarantines were overly strict and unnecessary. Today, people argue about the vaccine mandate’s ethical implications. The sad truth is that had Ms. Malone adhered to the conditions imposed at her initial release, she would never have been re-incarcerated. So, why didn’t she agree? Because she couldn’t make as much money in other jobs as she could as a cook. A constitutional freedom of employment? No such thing.

The Hypocrisy of it all, claiming violation of “Constitutional Rights”

Arguments have been raised claiming that the OSHA provision allowing formulation of an ETS is unconstitutional - a claim impliedly rejected by the Fifth Circuit in Asbestos Information Association v. OSHA

The bristling about constitutionality in the instance of vaccine mandates is quite self-serving. In other instances where clear constitutional rights are trampled on – nary a word is said. Let’s see how this plays out:

There is an undisputed constitutional right to travel, at least on the interstates (although that, too, can be curtailed in an emergency). It derives from the commerce clause and is governed by the federal, not state, government. [2]

Yet, we routinely queue up, remove our jackets, belts, hats, and shoes, pad barefoot into a scanner each time we travel by plane. The unlucky then suffer a fairly invasive pat-down by a complete stranger - before we replace belt, hat, jacket, walk barefoot to regain our shoes, and then embarking on our holiday or business flight.

I have yet to see social media or regular press or an anti-TSA movement protesting the invasion of this unquestionable constitutional right - which arose twenty years ago and hasn’t been removed or revised since.

To put this in context, 2,908 people died on 9-11, and another 549 Americans have died since then in terrorist attacks. As of this writing, more than 700,000 Americans have died of COVID.

So, what’s with the hue and cry about the constitutionality of a provision requiring workers to get vaccinated? Are those arguing on constitutional grounds grasping at straws?

[1] Hennington v. Georgia 163 U.S. 299 (1896)

[2] Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969)