In the last few weeks, there was a skirmish in the political battles involving the veterans of our efforts in Iraq, Afghanistan, and the rest of the Middle East, Jon Stewart, and PACT, the Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics Act. After a bit of posturing and strategy, PACT was passed. But what do we know about the burn pits beyond the sound bites?

Burn Pits – The military solution to waste management

“Burn pits have been used as a common practice by the United States military for more than two decades as a means of eliminating solid waste in a timely manner while maintaining operational security.”

At some point, we had 153 burn pits in Iraq, 99 in Afghanistan, and another 25 scattered about the Middle East. Balad Air Base had the largest of these burn pits, occupying 10 acres; at its peak, it burned 200 tons of solid waste daily – chemicals, medical and human waste, petroleum and its byproducts, rubber, plastic, metal, unexploded ordinance, “often ignited using ... Jet fuel Propellant (JP-8) as an accelerant.”

While burn pits were meant to be temporarily expedient, they proved so easy to operate and at such a low cost that they became the permanent approach to waste. Fun fact: Waste was burned rather than stored because burning was more environmentally friendly, avoiding groundwater contamination. Perhaps the environmental impact upon the air and those breathing that air may not have been so benign. The Department of Defense conducted air monitoring studies at Balad in 2007 and 2009. It was a hellish brew containing

- Volatile organic compounds and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons – “similar to those reported in major urban areas outside the US….”

- Polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and furans – “detected at low concentrations." While all dioxins are not the same, " species associated with greater toxicity were higher than generally found in the United States….”

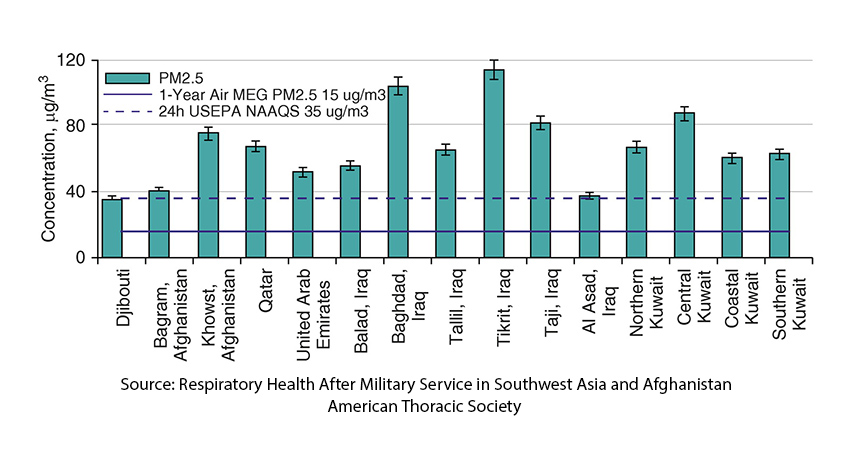

- Particulate matter – our old friends, PM10 and PM2.5, “on average higher than U.S. pollution standards.”

This is only a partial listing; other “criteria pollutants commonly monitored in the US” were not sampled, including the combustion products of household waste, geologic minerals, carbon from combustion sources, metals, and gaseous pollutants from combustion engines.

Particulate Matter

The 1-Year Air MEG PM2.5 level of 15 μg/m3 is slightly higher than our national standard of 12 μg/m3. But before we jump to the prominent narrative that the smoking gun is PM2.5 we should remember that this describes only the size of the particles, not the content; and in this instance, content may be important. A report by the Institute of Medicine noted that 54% of the PM2.5 came from sand dust, 30% from petrochemicals and combustion, 11% from traffic and 5% “from other anthrogenic sources.”

The 1-Year Air MEG PM2.5 level of 15 μg/m3 is slightly higher than our national standard of 12 μg/m3. But before we jump to the prominent narrative that the smoking gun is PM2.5 we should remember that this describes only the size of the particles, not the content; and in this instance, content may be important. A report by the Institute of Medicine noted that 54% of the PM2.5 came from sand dust, 30% from petrochemicals and combustion, 11% from traffic and 5% “from other anthrogenic sources.”

“…the most notable natural hazard in Iraq (and surrounding areas) are dust and sand storms.”

According to our NASA satellites, Afghanistan experiences between 2 and 6 dust storms monthly. In Iraq, there have been eight sandstorms in the last six weeks and has more “dusty days” (approximately 272) than non-dusty ones.

Dust storms were a frequent occurrence in the US in the “dust bowl” era of the 1930s. A public health report by the State of Kansas found some soil bacterial species in the dust, but what they found in far greater amounts was silica. Silica, like asbestos, can be taken in with our breath and, when lodged in our lungs, can cause inflammation and scarring – the medical term for this respiratory process is silicosis. Here are some of the findings of that Kansas report on health,

- “a 50 to 100 percent increase in pneumonia cases in their respective communities…”

- “very marked increase in the other complications of the acute respiratory infections, especially sinusitis. laryngitis, pharyngitis, and bronchitis.”

- “A comparison of death rates for the acute respiratory infections for the first 4 months of each of the past 4 years shows the rate per 100,000 for the 45 counties in 1935 to be 99 as compared with a State rate of 70.”

- “Reports from the principal hospitals in the dust area indicate a very high proportion of admissions for acute respiratory infections in the first 4 months of the present year.”

- “No evidence has been found that any pathogenic organisms were carried by the dust, and therefore the direct cause of the increase in respiratory infections could not be attributed to this factor. The dust, however, was exceedingly irritating to the mucous membranes of the respiratory tract, and in our opinion was a definite contributory factor in the development of untold numbers of acute infections and materially increased the number of deaths from pneumonia and other complications.”

Military Personnel Returning from Deployment

In a survey of 15,500 personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan in 2003-2004, 69% self-reported respiratory illness. In another self-reported survey the prevalence of wheezing was three-fold greater (19%) in those without asthma after deployment, and 25% greater in those with asthma after deployment.

The Department of Defense studies do find elevated adverse health outcomes.

“Significantly elevated rates of encounters for respiratory symptoms (IRR = 1.25; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.20-1.30) and asthma (IRR = 1.54; 95% CI: 1.33-1.78) were observed among the formerly deployed personnel relative to U.S.-stationed personnel.”

But, not necessarily due to burn pits.

“Personnel deployed to burn pit locations did not have significantly elevated rates for any of the outcomes relative to personnel deployed to locations without burn pits.”

Studies of lung function by spirometry [1], showed about 20% of symptomatic veterans had restriction of air flow, obstruction was present in another 5% both consistent with bronchiolitis – congestion and inflammation of our smaller airways. In another study involving biopsy of lung tissue,

“In 49 previously healthy soldiers with unexplained exertional dyspnea and diminished exercise tolerance after deployment, an analysis of biopsy samples showed diffuse constrictive bronchiolitis, which was possibly associated with inhalational exposure, in 38 soldiers.”

The Smoking Gun and PACT

In this instance, there are multiple environmental factors that have clearly resulted in elevated respiratory illnesses in our returning veterans. Dust, with silica may well be a primary mover, and our concern over burn pit exposure, while well founded in our experience with fire-fighters, may not be the smoking gun as it were.

That being said, we have a social and moral obligation to those who rose to our defense, certainly more than a “Thank you for your service.” The Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics Act bring new services to our veterans. Specifically,

- Extended the period of time a veteran can apply for VA health care “without having to demonstrate a service-connected disability.”

- Funding for more research on toxic exposures and their impact on veterans

- Routine screening for toxic exposures for our veterans

- A “new process for evaluating and determining presumption of exposure and service connection for various chronic conditions when the evidence of a military environmental exposure and the associated health risks are strong in the aggregate but hard to prove on an individual basis.” This includes a presumption of exposure based on 23 specific conditions and 16 geographical locations.

From a societal view, we are beginning to “do right” by our veterans. From a scientific point of view, the association of these adverse health effects solely with burn pits and no other environmental factors is a bit tenuous. By not fully investigating the more specific exposures of our veterans, we are losing an important opportunity - to better understand and target what in the chemical mix of what we term PM2.5, may be a causal factor.

[1] Spirometry consists of various breathing maneuvers where the force and volume of our inhalations and exhalations are measured.

Thank you to one of our most loyal supporters, JF, who asked the question about the basis for burn pits as the cause of veterans’ health disability.

Sources: Slow Burns: A Qualitative Study of Burn Pit and Toxic Exposures Among Military Veterans Serving in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Throughout the Middle East Annals of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience PMID: 35128459

Respiratory Health After Military Service in Southwest Asia and Afghanistan American Thoracic Society DOI: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201904-344WS

Assessment of the Department of Veterans Affairs Airborne Hazards and Open Burn Pit Registry. National Academy of Science