In October 2022, I wrote one of the first articles about xylazine (aka "Tranq"), a drug that was being used (especially in Philadelphia) to cut fentanyl, as if we need anything to make fentanyl more dangerous. But, as predicted by my colleague and frequent writing partner, Dr. Jeffrey Singer of the Cato Institute, we were witnessing nothing more than the "iron law of prohibition."

News reports about the growing presence of citizens among the mix of street drugs should come as no surprise to anyone familiar with what has come to be known as “the iron law of prohibition...An application of what economists call the Alchian Allen Effect, the concept was applied to prohibition (alcohol, cannabis, and other illicit substances) by Richard Cowan in the 1980s, who stated it simply: “The harder the enforcement, the harder the drugs.”

Dr. Jeffrey Singer in his Cato Blog, 9/23/22 (1)

As the anti-opioid zealots entrench (and enrich) themselves in their insulated, simple-minded world of "Opioid Speak," the iron law continues to operate. The result? More and sometimes deadlier drugs fill the void. There are hordes of them in the chemical universe, all patiently waiting in line for their turn to end up in a street drug envelope or counterfeit oxycodone pill, where they do...who knows what? A decade ago, would anyone have imagined that xylazine, a veterinary drug, would end up in packets of deadly illicit fentanyl where it would rot the limbs of those who injected it? Of course not – not more than anyone will be able to predict what's in the queue now. But here's one that has edged toward the front of the line: para-fluorofentanyl aka "Para," a simple analog of fentanyl, which is either more dangerous, less dangerous, or about the same. More on this later.

History of "Para"

"Para" was just another analog made by Dr. Paul Janssen, who founded Janssen Pharmaceutica in the early 1950s to address inadequate pain control. He was especially interested in discovering rapid-onset, potent pain medications. (2) One of them would become fentanyl.

Figure 1. One of the original fentanyl patents by Janssen. On the right is his drawing of the structure of the drug. Source: US Patent 3,141,823

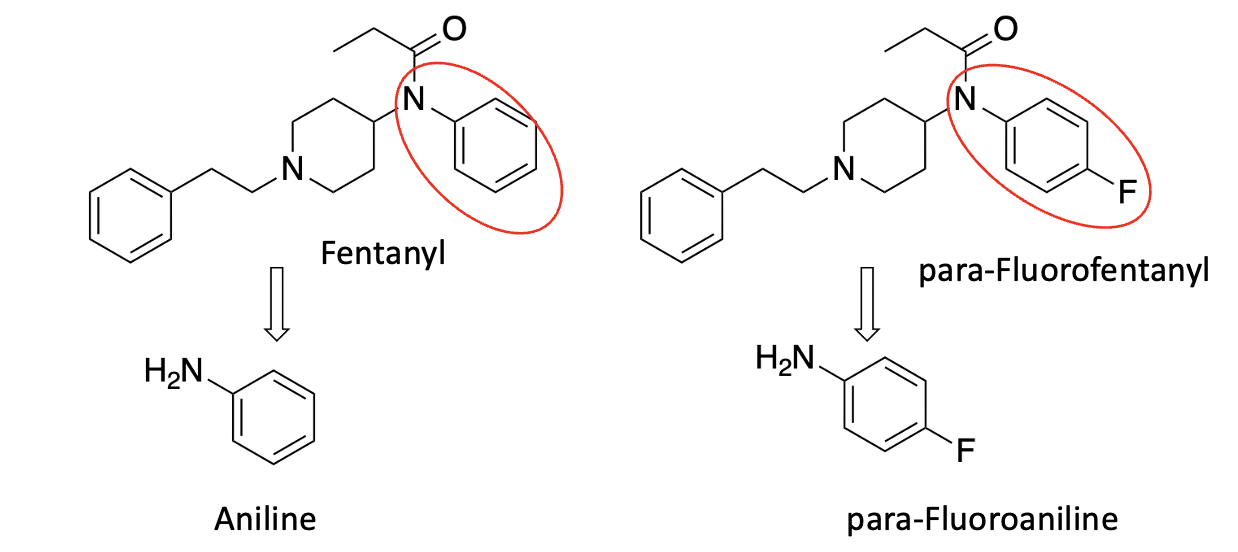

The synthesis of the two drugs is virtually identical; instead of using aniline one needs only switch to para-fluoroaniline, (Figure 2) which can be purchased from any of 31 vendors. But the real threat is far worse. There are more than 1,000 aniline derivatives that are commercially available. Any of them could be used instead of para-fluoroaniline, giving a new fentanyl-like drug with unknown properties. (Dear Feds: Good luck stopping this.)

Figure 2. Para-fluorofentanyl is among the simplest possible analogs of fentanyl. The two molecules differ only by the presence of a fluorine atom on the aniline ring. "Para" is made by using para-fluoroaniline rather than aniline as a starting material.

Prevalence of para-fluorofentanyl

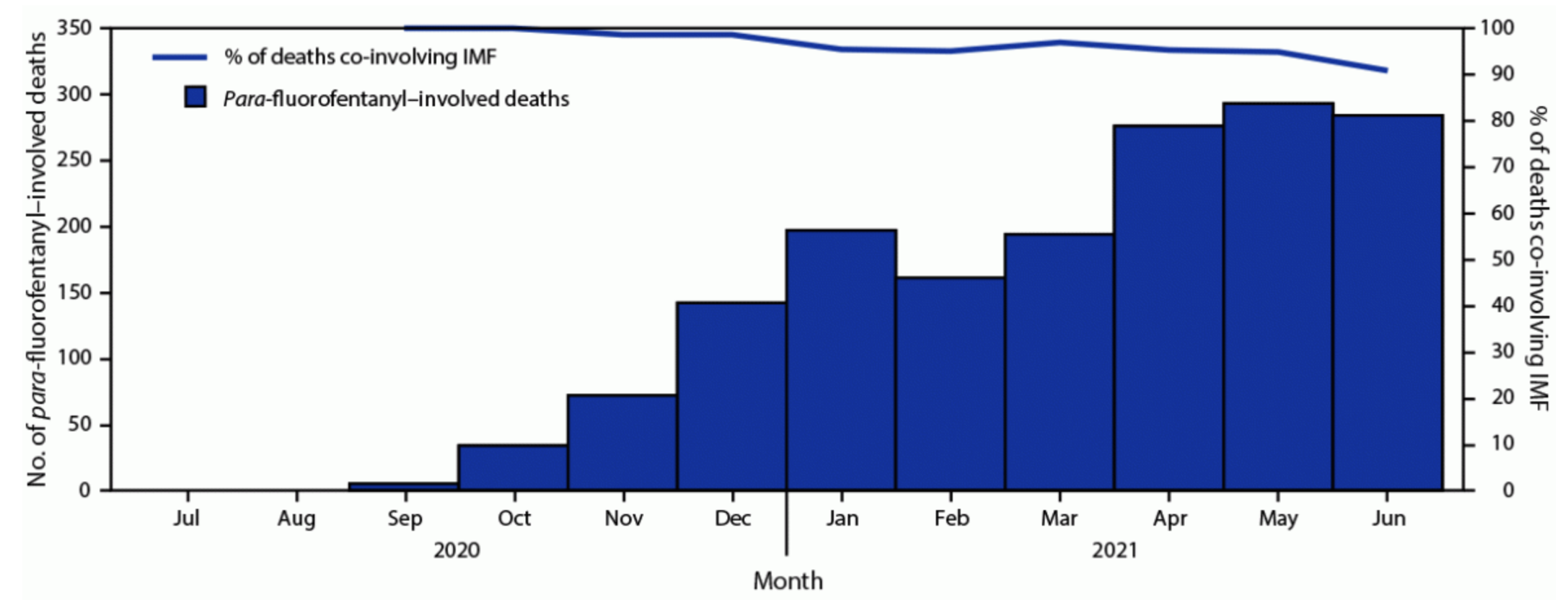

Although para may or may not cause the majority of deaths in the CDC graph below (Figure 3), its prevalence is surging. By June 2021, the drug was determined to be a cause of about 250 deaths, up from zero only a year before. In these cases, fentanyl involved was as well most of the time. Whether Para itself is a significant contributor to the overall death toll in the US is unknown, but it can't help. (An autopsy showed that the drug was part of the cocktail responsible for the death of actor Michael K. Williams famous for his role as Omar Little on The Wire.)

Number of para-fluorofentanyl-involved drug overdose deaths and percentage co-involved with illicitly manufactured fentanyl [IMF]

Source: State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, United States, July 2020–June 2021. Source: Notes from the Field: Overdose Deaths Involving Para-fluorofentanyl — United States, July 2020–June 2021

Is para worse than fentanyl?

This depends upon where you look; the drug has not been thoroughly studied.

- CDC: "Limited data suggest that para-fluorofentanyl is likely similar to or slightly less potent than [illicitly manufactured fentanyl]."

- Landmark Recovery, a rehab facility claims: "Clinical research indicates that para-fluorofentanyl (pFF) is much stronger than regular fentanyl." With no reference (!).

- A paper in the Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics (and good luck trying to understand this) shows that para binds more tightly than fentanyl to mu receptors by about 2-8-fold, suggesting it is a stronger drug.

Bottom line

Para-fluorofentanyl appears to be a more potent analog of fentanyl, but this is not the real story. As I wrote in 2018 (See Organic Chemistry Can Defeat Any Fentanyl Agreement), organic synthesis can overcome any scheduling of fentanyl precursor chemicals (and possibly the law) because of the infinite number of potential analogs that can be churned out, something the DEA is learning the hard way.

But the end result will be the same: The "iron law" will prevail, just as it has in the past decade when we have gone from opioid pills to increasingly worse illegal drugs: heroin, fentanyl, xylazine, para-fluorofentanyl...many others. What's next? Who knows? But history dictates it will probably become worse.

The fentanyl story is very far from the last chapter.

NOTES:

(1) Although in this particular instance, Dr. Singer was discussing nitazine, another horror show of a drug, the "iron law" applies equally to xylazine.

(2) Although "Para" was one of the analogs prepared by Jannsen, it was not developed as a drug. At least not legally. It appeared in a 1965 patent.