Two days of celebration in science happened in the last few weeks which, taken together, created a rather awkward situation.

The first were the announcements of the Nobel Prizes in Medicine, Physics and Chemistry, which were made on October 3rd, 4th and 5th respectively. These are great days for science - when scientists are honored for their hard work and topics such as autophagy, ribosomes and olfaction (our sense of smell) make headlines.

What a glorious day when two people can be overheard on the subway talking about vesicle trafficking!

Then, a mere week later, Ada Lovelace Day was celebrated. This day, started in 2009, is a celebration of women in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM). The goal of Ada Lovelace Day is to increase the profile of women in STEM, and in doing so, increase their presence and their notoriety. It was designed not only to support women who are already working in STEM, but, primarily to give young girls role models to emulate, in order to encourage them to enter into the STEM fields themselves.

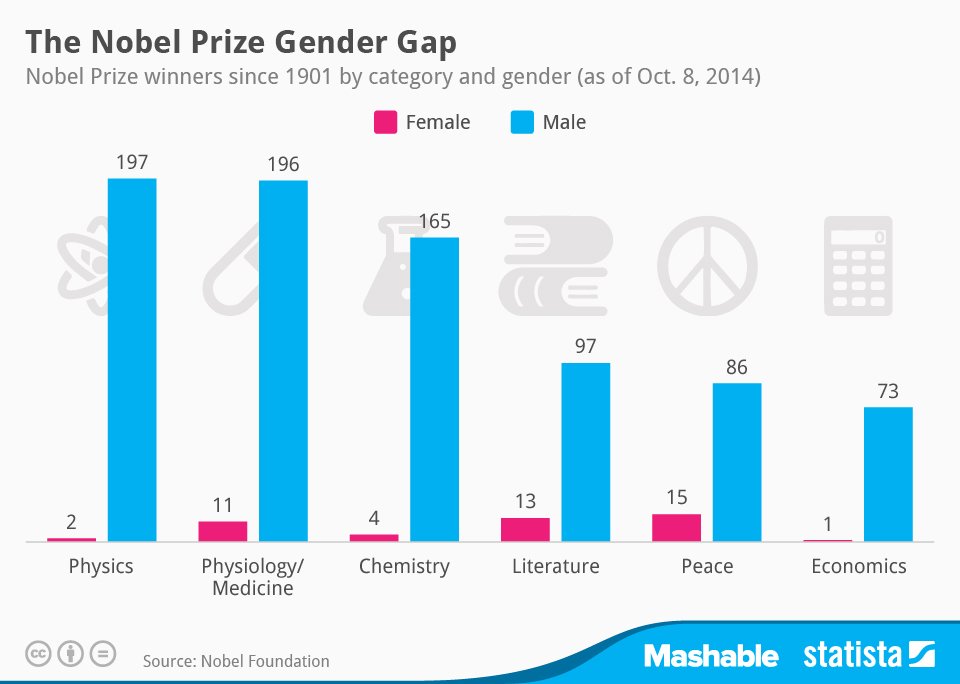

The importance of Ada Lovelace Day is made clear when you look at the Nobel Prize. As the graph below shows, since 1900, women have received just 5% of the prizes (46 out of 860 total recipients). If we subdivide the three science prizes, the prize for medicine and physiology is the highest (5.3% women), followed by chemistry (2.4%), and physics comes in last at 1% (that's just two women since 1900).

And, even when women do win the prize, they are often not given full credit. Dr. Nancy Hopkins, a professor at MIT and a member of the National Academy of Science, has spent a lot of time thinking about women in science, and also served as the Committee Chair of a group that looked into the inequalities that existed between male and female faculty at MIT and published a study called "A Study on the Status of Women Faculty in Science at MIT." Dr. Hopkins says, “I have found that even when women win the Nobel Prize, someone is bound to tell me they did not deserve it, or the discovery was really made by a man, or the important result was made by a man, or the woman really isn’t that smart. This is what discrimination looks like in 2011.”

Whew - thankfully, no one will be saying that this year - because all (all) of the recipients of the 2016 Nobel Prizes were men.

The gender gap is complicated, with many facets; so much so that Nature devoted an entire edition to the topic in 2013. And, we certainly don't expect to be able to solve it here and now. But, the juxtaposition of a day of celebration to inspire young girls with the message that they won't achieve the fields highest honor is something that we could not leave unnoticed.

Because women are not getting the Nobel Prize, does not mean, necessarily, that we are not making strides in equality.

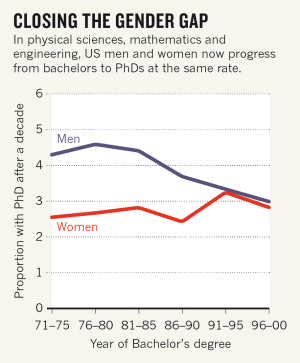

So, how are women progressing in science, up until the Nobel Prize winning stage? Well, the gender gap has closed, in some ways, regarding STEM disciplines. For example, the ratio of women and men getting PhDs is currently 50/50 (see graph below).

However, it is after the degree granting stage that things start to go awry. Only 18% of full professors in the biological sciences are women - only 14% for physics.

It has been shown that women do not apply for faculty jobs as frequently as men do, essentially taking themselves out of the running. It has also been suggested that women tend to shy away from professions where sheer talent is perceived to be valued over hard work - a category that the sciences typically fall into.

Another study showed that who runs the lab, and how famous that person is, may be a factor. Men who are the heads of labs have 36% women postdocs (female-run labs have 46%.)

Interestingly, the most prestigious labs, specifically, tend to hire more men than women as their post-docs (the position that is taken after obtaining a graduate degree.) This is an important facet of this conversation because a scientist trained in a prestigious lab is more likely to win an academic position than someone from a lesser known lab. The study found that the more esteemed the professor, the worse the ratio was. In labs that are run by very distinguished male professors, the number of female postdocs was only 31%. In contrast, as women became equally as distinguished, the number of females in the lab did not change. And, in the labs of Nobel prizewinners, (22 in the study) there were three male postdocs for every female.

Of course, this is not true for every top scientists' lab. I did my post-doc in the lab next to Dr. Bob Horvitz (the 2002 winner of the Nobel Prize) for years at MIT and can safely say that his lab was a place of equality. Checking his website today, there are three female and two male postdocs. Additionally, Dr. Richard Axel, another Nobel Prize winner, has trained several notable female scientists including Dr. Linda Buck. In fact, Dr. Axel and Dr. Buck won the Nobel Prize together, in 2004.

So, perhaps it is not so much a question of why women are or are not in science, rather why do they not make it into the most esteemed, highest levels of science at the same rate as men. But, with the data suggesting that it takes highly esteemed female scientists to promote younger female scientists, we are stymied by this bottleneck that exists. And, the message to young girls cannot be, feel free to go into science - but, don't think that you'll achieve as much as men do.

And, so, we are brought back around to Ada Lovelace and giving young girls the role models that they need in order to go into STEM with the expectation that they will be treated the same as men - all of the way up to the Nobel Prize.

Here are listed the increcible women who are Nobel Laureates.

The Nobel Prize in Physics

1963 - Maria Goeppert Mayer - nuclear shell structure

1903 - Marie Curie - radiation

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry

2009 - Ada E. Yonath - structure and function of the ribosome

1964 - Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin - using X rays to determine biochemical structures

1935 - Irene Joliot-Curie - made new radioactive elements

1911 - Marie Curie - discovery of radium and polonium, by the isolation of radium

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

2015 - Youyou Tu - Malaria therapies

2014 - May-Britt Moser - spatial memory in the brain

2009 - Elizabeth Blackburn and Carol W. Greider - telomeres on the ends of chromosomes and telomerase

2008 - Francoise Barre Sinoussi - HIV

2004 - Linda Buck - olfaction

1995 - Christiane Nusslein-Volhard - genetics of enbryonic development

1988 - Gertrude B Elion - principles of drug treatment

1986 - Rita Levi-Montalcini - discovery of growth factors

1983 - Barbara McClintock - mobile genetic elements

1977 - Rosalyn Yalow - development of radioimmunoassays of peptide hormones

1947 - Gerty Cori - conversion of glycogen