When trying to identify why many children gain weight at an early age, the conversation always seems to include the idea that schools, with their scheduling constraints and ever-tightening budgets, find it increasingly difficult to fund or create periods of physical activity, like gym classes or field trips. And even if they are allocated periods outside of the classroom, technology is eating up more and more of their free time.

And then there are the school cafeterias. They tend to be a favorite target of critics, who contend that lunches being served are neither nutritious or appealing enough. And with all that, we collectively shrug.

But a new, large study of young children indicates that schools are being unfairly implicated in this regard, and that significant weight gain is taking place at home -- specifically, during summers away from school.

"The risk of obesity is higher when children are out of school than when they are in school."

This is the straightforward conclusion of a new study using nationally representative data to determine whether the causes for significant weight gain and childhood obesity "lie primarily inside or outside of schools." Titled "From Kindergarten Through Second Grade, U.S. Children's Obesity Prevalence Grows Only During Summer Vacations," the study focused on 13,006 young children from 846 schools extending from the fall of kindergarten in 2010 to the spring of second grade in 2013.

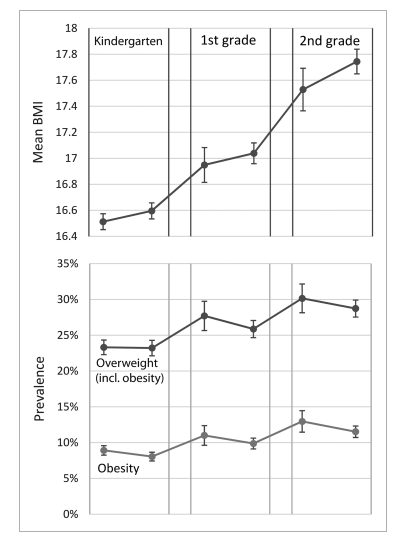

The paper describes the research collected in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 2010–11, which recorded kids' weight, height and body mass index (BMI) at six different intervals, once in the fall and spring, over the three school years.

"On each occasion, height and weight were measured twice," explained the study's co-authors Paul T. von Hippel from the Center for Health and Social Policy, LBJ School of Public Affairs, University of Texas, and Joseph Workman, from Nuffield College, University of Oxford. During the study period, "the prevalence of obesity increased from 8.9% to 11.5%, and the prevalence of overweight increased from 23.3% to 28.7%. All of the increase in prevalence occurred during the two summer vacations; no increase occurred during any of the three school years."

"On each occasion, height and weight were measured twice," explained the study's co-authors Paul T. von Hippel from the Center for Health and Social Policy, LBJ School of Public Affairs, University of Texas, and Joseph Workman, from Nuffield College, University of Oxford. During the study period, "the prevalence of obesity increased from 8.9% to 11.5%, and the prevalence of overweight increased from 23.3% to 28.7%. All of the increase in prevalence occurred during the two summer vacations; no increase occurred during any of the three school years."

Meanwhile, "On average, BMI growth rates were faster during the summers than during the school years."

The study seems to be based on considerable and significant data, having taken place over years with a large number of participants. However, one potential issue is that, as the authors concede "our data do not permit us to estimate weekend or after-school BMI gains," meaning that the study cannot account for "some out-of-school risk factors [that] affect children not just during the summer."

Overall, however, the findings of the study do tend to suggest that during the summer young kids are eating more high-calorie foods and playing less. They may also be increasingly distracted by technology, which encourages them to sit still. Meanwhile, other studies, like this one involving 7-year olds, have concluded that "short sleep duration was shown to be an independent risk factor for obesity/overweight." So in addition, it may be that young kids, in general, are also not getting enough shut eye in the summer.

Schools may have have their shortcomings, but this problem of childhood weight gain and obesity appears to have many contributing factors. In addition, this is not to say that parents are the villains here. But what this study appears to demonstrate is that when it comes to an apparent lack of physical activity at school not everything is what it appears. And finally, that families should take a closer look at their summertime routines in order to get kids moving and sleeping more, and eating better.