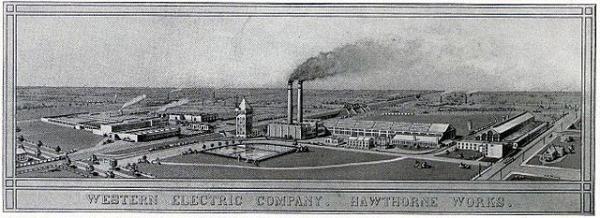

In an attempt to increase the productivity of their workers, management of the Western Electric Company looked to see if providing more light in the factory made for better workers. And sure enough, even small changes in the lighting affected productivity. Except of course that it wasn’t true. Another researcher determined that the effect was not due to the lighting at all, but to the attention paid to the workers. He dubbed this effect, that observation can influence behavior, the Hawthorne effect. [1] Physicians who are increasingly required to report patient outcomes publically have argued back and forth about how observation may influence their decision making. JAMA Cardiology is publishing another of these studies.

Several states require the public reporting of patient outcomes to provide the public with information guiding them in their selection of physicians and hospitals. Coronary artery procedures, either stenting (formally called percutaneous coronary interventions, PCI) or open surgery take up a lot of healthcare resources and have been the low hanging fruit of these public registries. The study surveyed the opinions of about 150 interventional cardiologists in New York and Massachusetts, an admittedly small sample. These were well-established physicians practicing in large volume hospitals.

- 60% felt they were pressured by colleagues not to perform indicated stenting because of a high risk of death.

- 65% reported avoiding these procedures at least twice because of “concerns of a negative publically reported outcome.

- 95% felt other interventionalists acted the same way.

- 50% felt that their superiors (or peers) would not support their judgment when the patient died from complications of stenting.

- 73% did not trust the methods behind the risk adjusting the reports. [2]

- Cardiologists with greater experience were less likely to report feeling pressured, had more faith in risk adjustment methodology and were less likely to other cardiologists avoided high-risk procedures.

The authors concluded that public reporting “engenders aversion toward high-risk PCI.” But is that so bad? Now some might say that avoiding complications and deaths by avoiding excessive risk in responsible behavior. Others would argue that when faced with an increased risk of dying, many people, physicians, and their patients would opt to “do everything possible.”

For me, admittedly not as adverse to risk at some of my peers, knowing the patient’s wishes is part of risk assessment and is never taken into account in these public records. The other finding that should prompt some greater thought and research is why the more experienced (older) cardiologists felt differently. In part, it is the confidence in your judgment that develops over time. It is also a bit of a numbers game, one death in 30 cases reads much differently than one death in a hundred. Summary statistics would say the difference was three-fold. But what if that one death was a high-risk patient for the cardiologist who treated 30 patients, and a low-risk patient for the other physician? Does that change your thinking and more importantly, since the data is meant to be useful to patients, how is a patient going to understand the differences, especially when you need treatment now, and there is not a lot of time to shop around for your best deal. It seems that our best efforts to shed light on a problem come with unanticipated shadows.

[1]In all likelihood, both the original researcher and Harry Landsberger, who originated the term the Hawthorne effect, were wrong. A later review of the original data showed that all of the changes in lighting were made on Sunday, so as not to interrupt the work schedule. Workers returned on Monday, rested and ready to turn out more widgets.

[2] Patients more acutely ill, say whose heart is unable to sustain an adequate blood pressure without continuous life-saving medications have different outcomes than patients coming in electively to treat their chest pain. Risk adjusting takes these differences in severity of patient illness into account in determining whether the complications or death was “acceptable.” (No one like to believe that any death that we had a hand in is acceptable)

Source: A Survey of Interventional Cardiologists’ Attitudes and Beliefs about Public Reporting of Percutaneous Coronary Interventions JAMA Cardiology DOI: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1095