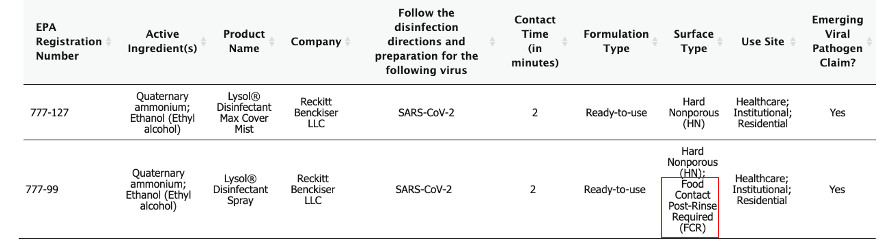

It's been pretty much impossible to buy a can of Lysol spray since the COVID nightmare began about seven months ago. Good luck getting the stuff now; the EPA has approved two sprays, Lysol Disinfectant Spray and Lysol Disinfectant Max Cover Mist. In a press release, the agency said;

Last week, EPA approved two products, Lysol Disinfectant Spray (EPA Reg No. 777-99) and Lysol Disinfectant Max Cover Mist (EPA Reg No. 777-127), based on laboratory testing that shows the products are effective against SARS-CoV-2.

EPA Press release. July 6, 2020

If you're asking "what's so special about those two sprays?" or "what's in there that kills the coronavirus?" the answer is rather simple: alcohol and a common detergent. But it's not the stuff you wash your laundry with. It's a different kind of detergent.

To understand the difference we need to delve deep into the bowels of one of the most despised of all the sciences. Faithful readers surely know what's coming now...

Yes, boys and girls. It's time for The Dreaded Chemistry Lesson From Hell®! So here it is, back by unpopular demand.

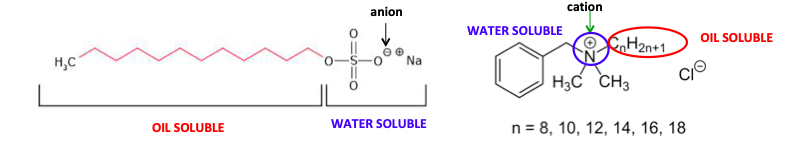

The two most common classes of detergents (Figure 1) are cationic (having a positive charge) and anionic (having a negative charge). Although they are structurally different, they have two essential properties in common - a water-soluble (polar) group on one end of the molecule and an oil-soluble group on the other. The combination of the two in one molecule gives it both oil and water solubility. This is why soaps and detergents will clean a greasy plate (1).

Figure 1. (Left) An anionic detergent containing a lipophilic (oil-loving) carbon tail and a hydrophilic (water-loving) head having a negatively charged sulfate group. (Right) A cationic detergent containing a long lipophilic carbon chain (red) and a polar hydrophilic quaternary nitrogen (a nitrogen atom with four alkyl groups bound to it). Quaternary ammonium detergents (called "quats") are typically a mixture containing different length carbon chains, which give the detergent different properties.

Although anionic and cationic detergents both wash stuff, the anionic type is better at cleaning (laundry detergent) but the quats are better at disinfecting, especially when combined with alcohol, killing bacteria, viruses (2), and yeast.

Who Cares?

Well, the Reckitt Benckiser company which sells Lysol cares plenty, because right now its two brands are the only products that are EPA-approved to kill coronavirus. You should care too because the sprays quickly killed the bug on hard surfaces in between 1-5 minutes, as was demonstrated in a May 24 letter to the editor in the American Journal of Infection Control. Below are the product labels. They are very similar. It is impossible to tell from the label exactly which "quats" are where, but it usually makes little difference.

Here are the labels of the two products. They are almost identical.

How do quats kill viruses?

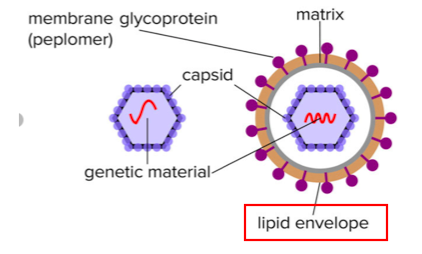

There are two types of viruses, enveloped and non-enveloped. Enveloped viruses contain an extra layer of "protection" called a lipid envelope, which, ironically, makes them more susceptible to being killed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Non-enveloped (L) and enveloped (R) viruses. Image: Research Gate

Think of an enveloped virus as an apple covered in butter. A soapy sponge will clean off the butter but leave the apple intact. In this case, the quat is the soapy sponge. But the analogy breaks down here; unlike the apple, once the envelope is damaged the virus is toast. Viruses without envelopes (e.g., norovirus) are more difficult to kill. Coronavirus has a lipid envelope.

Does this approval really matter?

That's not clear. While it is comforting to spray and kill the little bastards, it is becoming more and more clear that respiratory droplets (person-to-person) are the primary mode of transmission and that surfaces play a less important role than once thought. Nonetheless, it can't hurt to better disinfect surfaces that are often touched by the public.

Can you spray Lysol in the face of people who will not wear masks?

Regrettably, no.

NOTES:

(1) Soap is also an anionic detergent as you can see from its chemical structure. Shown below is sodium laurate, a common soap. Note the charged (polar) oxygen on the left and the lipophilic 12-carbon chain in blue.

(2) You can't technically kill a virus because it's not alive.