A recent press release from the FDA announced that Royal Aruba, an Aruba-based company, issued a voluntary nationwide recall of the company’s Aruba Aloe Hand Sanitizer Gel and a few other products. This recall was prompted by the discovery that some batches contained varying amounts of methanol contamination in addition to ethanol, the chemical responsible for the effectiveness of hand disinfectants.

Methanol poisoning can result in a number of symptoms – blindness is common – and can be caused by inhalation, skin contact, and oral consumption, the most dangerous route of administration. It is unclear whether the tainted lots would have been harmful if used as directed; this would depend upon the amount of methanol contaminant present and how often it was used. But this is not a chance you’d want to take, especially if children are in the house and could potentially swallow it. As little as two tablespoons can be fatal to children. (1)

How did methanol get into the products?

This is not known, but here's my best guess: Denatured alcohol was used rather than pure ethanol, either intentionally – to save money – or due to manufacturing incompetence. Alcohol can be denatured by adding one of several toxic chemicals to it to make it undrinkable. The chemical most commonly used is methanol, and it is this that makes drinking denatured alcohol a bad idea. Part of the problem is that it's not trivial to remove methanol from a methanol-ethanol mixture. Here's why.

During Prohibition – between 1920 and 1933 – an estimated 10,000 people in the US died from methanol poisoning. Some of the deaths resulted from people drinking denatured (intentionally poisoned) alcohol. Others succumbed from drinking "naturally-produced" methanol, which is a contaminant caused by source of the improper use of moonshine stills.

Meet Marvin "Popcorn" Sutton, the King of Moonshine

Here's quite a character, especially for fans of Americana - Marvin, "Popcorn" Sutton. Sutton operated his stills well after Prohibition was repealed (1960s-70s) but doing so remained illegal because the alcohol avoided the federal alcohol tax – something that the Federal government didn't much care for. Nor did Sutton much care for the government...

(Left) Marvin "Popcorn" Sutton and his still. (Right) Sutton's gravestone displays his animus toward the US government. You know the word. Photos: Flickr, Find a Grave

Sutton was in perpetual trouble with the law, especially for moonshining and bootlegging (2), but he managed to avoid prison until 2009, when he was convicted of illegal possession of a weapon and a whole lot of untaxed alcohol. In 2009, Sutton committed suicide rather than reporting to a federal prison. His story was the subject of a History Channel documentary called "Hillbilly: The Real Story."

One of Popcorn Sutton's stills from eBay. Probably not free shipping.

Popcorn did it right: Throw away the first cut.

Sutton, who came from a family of moonshiners, knew his craft well. What does this have to do with poisoned hand sanitizer? Plenty.

Buried in this story is a chemistry lesson about a purification technique that many chemists dislike intensely —distillation (it's just a pain in the ass and often doesn't work very well). During a typical distillation, a mixture of liquid(s) is gradually heated in a flask or vessel. Since different liquids vaporize at different temperatures (their boiling point), as the flask continues to heat, the liquids with the lower boiling point will vaporize first. The vapor then passes through a cooling condenser, which converts it back to its liquid form and is collected. This is no different from how a still works. One potential problem: Although distilled liquids are usually pure, they may not be pure enough, especially if you don't know what you're doing. Then, bad things can happen.

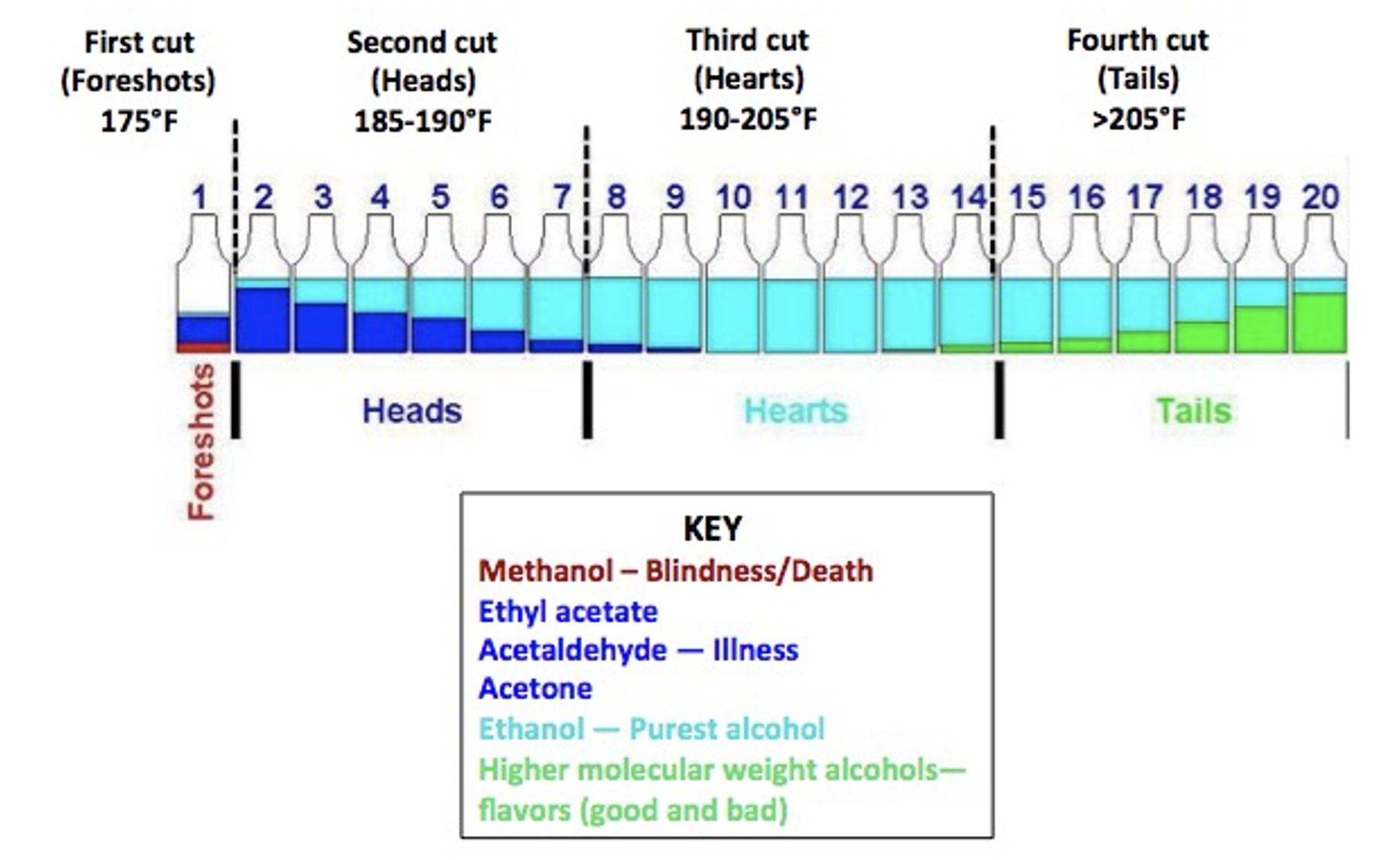

Distillation is useful for separating mixtures of liquids with different boiling points or for collecting a liquid, such as alcohol, from a mixture of solids and other liquids. In a still, the crude soup-like material from fermentation is called a mash and it has all sorts of stuff in it. You'd better do it right, or your customers will be mighty sick (or mighty dead) because distillation isn't especially effective in separating liquids with similar boiling points (methanol boils at 65oC while ethanol does so at 80oC – not much of a difference. When trying to separate two liquids with similar boiling points, co-distillation — both of them distilling at the same time – is common. This is why moonshiners need to "throw away the first cut." (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The chemical composition of moonshine as a function of distillation temperature. Note that the "first cut" contains little or no alcohol, just other chemicals formed during fermentation and methanol. Adapted from Whiskey Still Pro Shop and Stilldragon.org

Where does the methanol in moonshine come from?

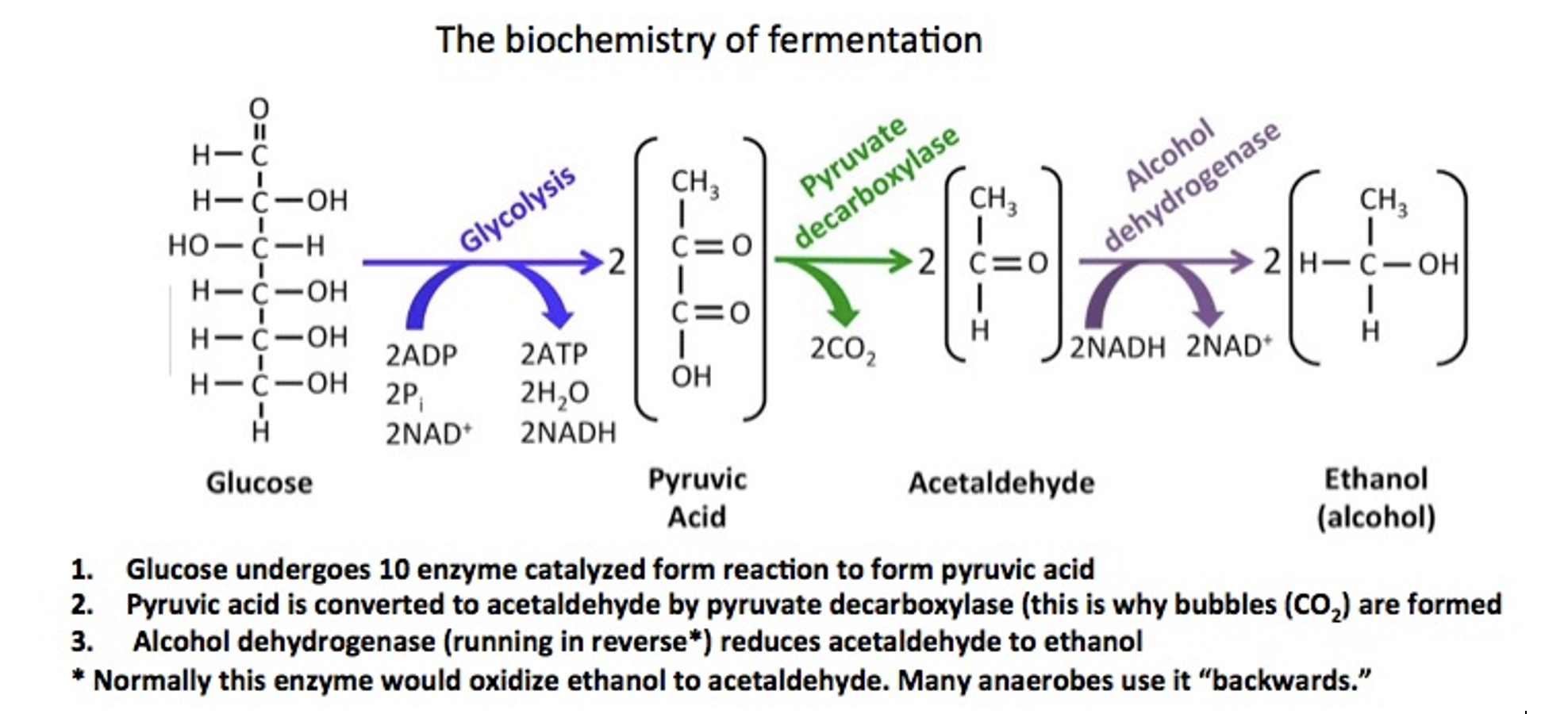

The fermentation of alcohol (Figure 2) begins with glucose and involves 12 well-known biochemical reactions. The first phase, glycolysis, consists of a series of ten separate reactions that convert glucose into pyruvic acid, but only in the absence of oxygen. Pyruvic acid then undergoes an enzymatic decarboxylation (this is why gas forms during fermentation - CO2), which converts it to acetaldehyde. Finally, the acetaldehyde is reduced to ethanol by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase. Yeast can do a lot of cool things.

When sugars are anaerobically metabolized by yeast (Figure 2), drinking alcohol is formed, but so are byproducts, like methanol, aka wood alcohol acetaldehyde, and ethyl acetate. Figure 1 points out the "messiness" of fermentation, the importance of differences in boiling point in distillation, and some of the limitations of the technique as a purification method.

Figure 2. Fermentation of alcohol by yeast.

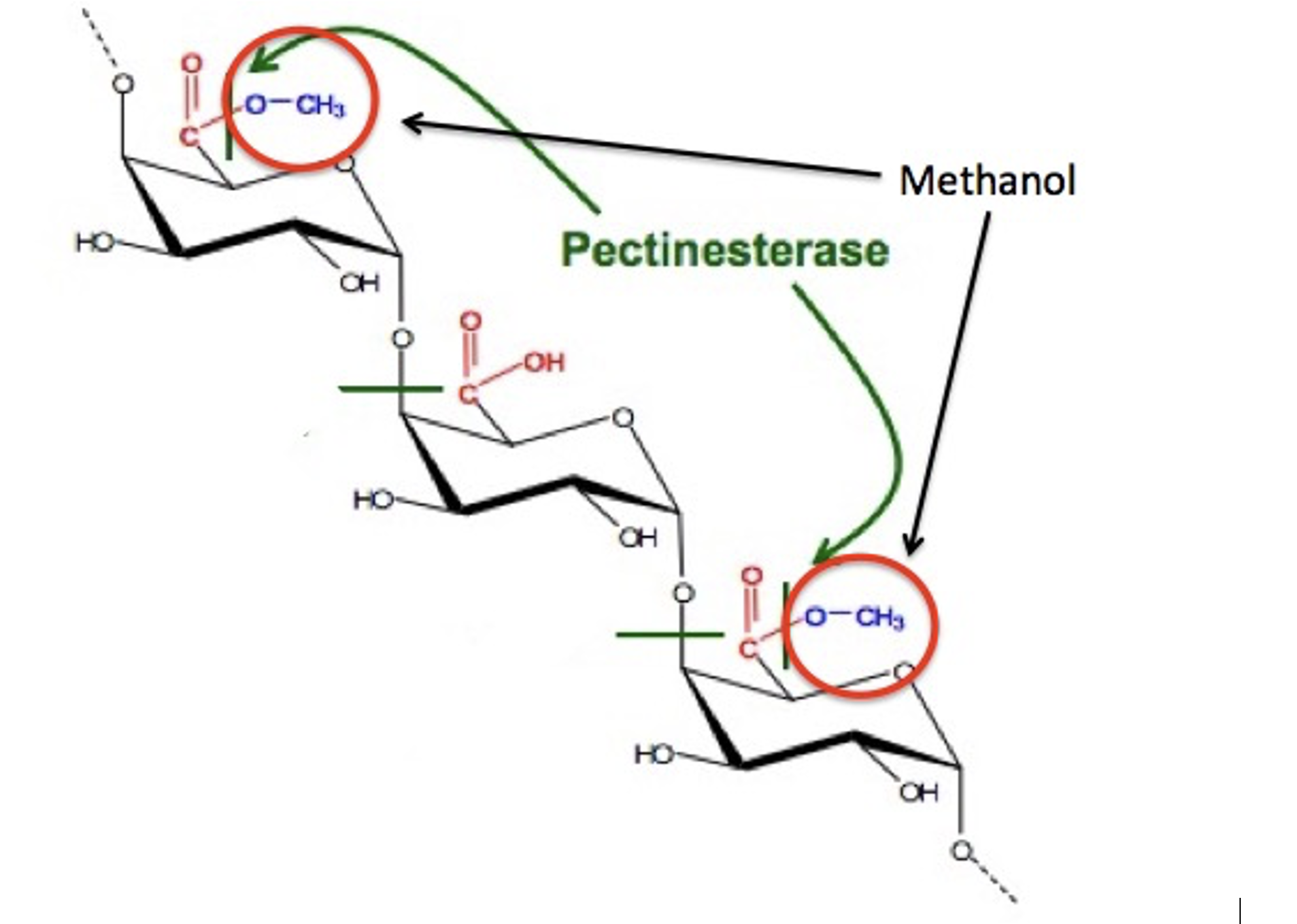

But where does the methanol in the first cut come from? Nothing in Figure 2 suggests that it should be there. It turns out that the methanol is formed in an unrelated process— from the methyl ester (red circle) in pectin. Pectin is found in fruit, so when berries, etc., are used as the sugar source, methanol is formed. When molasses is used as the sugar source, methanol is not formed. Traditionally, moonshine is made from corn, which has pectin.

So, there you have it. The issue with the recalled hand sanitizer may very well be the same problem that moonshiners ran into a century ago – the inability to remove the methanol impurity from alcohol.

Now you can make your own booze and try to screw the US out of the alcohol tax. Popcorn would be proud. Provided that you remember to throw away the first cut.

Notes:

(1) A lethal dose of methanol is estimated to be 10-30 mL. By contrast, the amount of methanol in a package of aspartame is 10 mg. It would take 790 packets of aspartame to equal 10 mL of methanol, yet people are still hysterical about it despite decades of safe use. Enough to make you want to drink.

(2) Moonshine gets its name because it was traditionally made at night to evade law enforcement. The term bootlegger is derived from the practice of transporting alcohol (during times of Prohibition) but transporting it in high boots.