It is bad enough when unqualified pundits offer dumb opinions about science, but bad legislation can cause real damage.

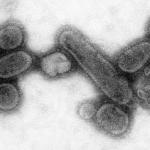

biological weapons

There's something irresistible about conspiracy theories.

Among the apocryphal quotes is that of Robert Oppenheimer, upon the detonation of the first atomic bomb: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” A policy discussion in Science echoes those concerns about horizontal environmental genetic

Just like fingerprints, we all have a unique set of behavioral quirks.

In foreign policy, it is difficult to state anything with certainty. Intelligence agencies have sources that journalists do not. As a result, publicly available information is often incomplete.

When North Korea makes the news, it's usually due to its nuclear missile program. That is certainly a very realistic threat. Just yesterday, U.S.