It could be argued that there is no more polarizing composer than Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Both performers and listeners have very different reactions to Mozart's works. He comes naturally to some pianists but also inspires fear among others who, despite the fact that they can play Rachmaninoff or Liszt, both far more technically challenging, know that there is nowhere to hide when playing Mozart. There are no eight-note chords, just seemingly simple melodies (1), decorated with scales, arpeggios, and trills. Don't even think about over-relying on the sustaining (2) pedal. A big no-no. Mozart is all about touch. A light touch. A Mozart touch. It's much the same with people who listen. Some people can joyfully listen all day while others think he lacks substance.

Although he didn't invent it, Mozart defined the concerto - a composition with a soloist accompanied by an orchestra. And Mozart's soloists were usually pianists. His 27 piano concertos, most of which were written between 1782 and 1786 (!), are considered by some as one of the greatest bodies of classical music ever composed (There is plenty of controversy here too.)

Here's something you may not know, and it probably explains his productivity. Mozart had a formula which he used for his concertos and he rarely deviated from it. So, if a Mozart aficionado is listening to a concerto which he/she has never heard that person will usually have a pretty good idea of what's going to happen next. Here's the formula.

All 27 concertos consist of three movements. The first and third movements are fast and light, usually, Allegro, and the second movement (and this is where you're really going to need the touch) is slow and expressive, either Adagio or Andante. (3)

If you're the piano soloist you will need some real patience and also steely nerves. Almost every movement of every concerto begins with a very long, usually 1-2 minute, introduction during which time only the orchestra plays. This passage sets up the main theme for the pianist, who by the time he or she starts has been sitting there doing nothing except trying not to have a nervous breakdown. Finally the piano starts, and for about five minutes there is an interplay between the orchestra and piano. This is the body of the movement. Then, abruptly, things come to a dead stop at about the same time in every movement and always on the same chord. To understand this you need a little music theory. I'll try to make it as little as possible.

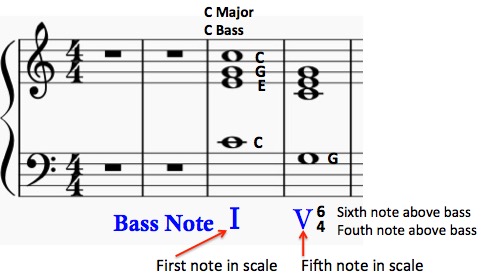

Most Western music is based on major and minor scales. The chords that make up the harmonies are set combinations of the notes in that scale. Below is the simplest scale; C major has no sharps or flats (black keys). Each note in succession gets assigned a number (Figure 1). Three or more notes together form a chord.

Figure 1. The C Major Scale Image: MyPianoWorld.com

In four-part harmony (4) in the key of C major, the root chord, which is the same chord that the piece starts and finishes with, consists of the first note in the scale (C), the third (E), the fifth (G), and the eighth (C), which is one octave above the bass note. So, C-E-G-C is a C-major chord, the simplest of them all. Yankee Doodle begins and ends with a C-major chord; the first and last chords are the same. Your ear hears this as normal.

But things can get a little hairy. Because (Figure 2) there are actually three possible C-major chords, each differing only by which of the three different notes is the lowest (bass) note. In a C-major root chord, the bass note will always be C. When the bass note is E this is called a first inversion chord (5). Even though it is composed of the same three notes (C, E, G) as the root chord, its sound is very different. Taking it a step further, when the bass note is G this is called a second inversion chord and it is very important in Mozart's piano concertos - all of them. In music theory, this chord is also called a V-6-4 chord. The V the Roman numeral which signifies that the fifth note in the scale (G) is the bass note. The 6 and 4 refer to the interval of the other two notes. E is six notes above G; the interval is called a sixth. C is four notes above G. This is called a forth.

Figure 2. Two of the three possible C-major chords. The root chord is on the left. The bass note, C, is designated by a Roman numeral, in this case, I. (Right) The second inversion chord has G as the bass note and is designated by the Roman numeral V. The 6 means that the highest note is E, which is a six-note interval higher than the bass note. The 4 means that the note below it, C, is a four-note interval from the bass note.

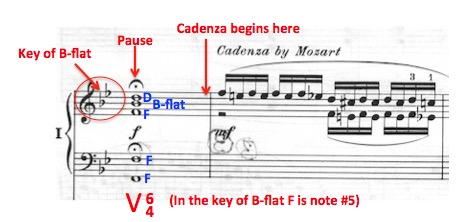

Although a second progression (V-6-4) chord may be played at any time throughout the piece, about three-quarters of the way through the movement, things come to a dead stop, both musically and time-wise. When you hear the music pause on a V-6-4 chord you will automatically think "OK, now what?" It would sound very strange and incomplete if the piece ended right there. (6) This natural break is accentuated by a 2-3 second pause, which precedes the cadenza, a piano solo of roughly one minute during which the soloist gets to strut his/her stuff (Figure 3). The cadenza is usually showier and technically more difficult than the rest of the piece. Sometimes other composers write the cadenza, but this is unusual. Here's a real one.

Figure 3. Mozart's Piano Concerto #11 in F, 2nd movement. V-6-4 chord followed by a pause, then the beginning of the cadenza, which is clearly seen as composed by Mozart himself. In the V-6-4 cord note #5, F, is the bass note. Six, and four notes higher are B-flat and D respectively.

The cadenza leads seamlessly back to the orchestra, which finishes the movement about 30 seconds later. The pianist usually does not play during this time. So, with few exceptions, a solo pianist will neither begin nor end a single movement in a Mozart piano concerto.

So, that's it. Perhaps the greatest composer ever used a formula for his finest work. That's one winning formula.

If you slogged through this you deserve a reward, and you're about to get a seriously beautiful one. Mozart's 23rd is probably his most famous and most popular piano concerto (7). The first and third movements are lively melodic, and catchy; the second - the only second movement Mozart wrote in a minor key, is hauntingly beautiful. Here is the hauntingly beautiful Hélène Grimaud performing Mozart's 23rd Piano Concerto. This is something special.

NOTES:

(1) Mozart's themes and harmonies are only simple to those who can't understand them. They are anything but.

(2) The piano has three pedals. On the left is the soft pedal. On the right is the sustaining pedal, as its name implies, acts like you are still holding down the keys even when you are not. I have never once used the one in the middle. In some pianos, it can be used for silent practicing. I think it's stupid.

(3) Allegro means fast. Adagio means slowly. Andante means "at walking speed," which puts it somewhere between Allegro and Adagio. There are many incremental tempos both in the middle of this range and outside of it. These three cover much of Mozart's work.

(4) Four-part harmony, which is the basis for much of classical and Western popular music is based on the formation of chords from the notes in major and minor scales. Other types of music are built around other scales and have very different sounds, especially Jazz.

(5) You've all heard a first inversion chord. Think of the second chord in the guitar solo of "Layla." The bass progression is root (C bass)-first inversion (E bass), then to F-major with an F bass. Now you'll know what you're hearing.

(6) It In music theory, the V-6-4 is referred to an unstable chord - one that needs to be resolved. It is no accident that it precedes the cadenza.

(7) Mozart's 23rd piano concerto was Josef Stalin's favorite piece of music. He died in 1953 while listening to it.