Having played the piano for most of my exceedingly long life (Mozart was like a little brother), there is absolutely no doubt in my mind that major and minor chords and the music based upon them are perceived very differently – major chords are "happy" and "uplifting," while minor chords are typically associated with feelings of "sadness" or "somberness." Many dismiss this as merely a function of our exposure to Western music, but my ears tell me otherwise, as do some interesting quasi-scientific theories.

Major vs. minor. A difference of 19 Hz is both small and large.

Picture a square dance written in a minor key. It might go like this.

Around your partner do-si-do

Around your partner here we go

Around your partner and you’ll see

How much fun suicide can be.

Clearly, this attempt falls flat, much like playing Looney Tunes themes at a dirge. More on this later.

A bit of music theory

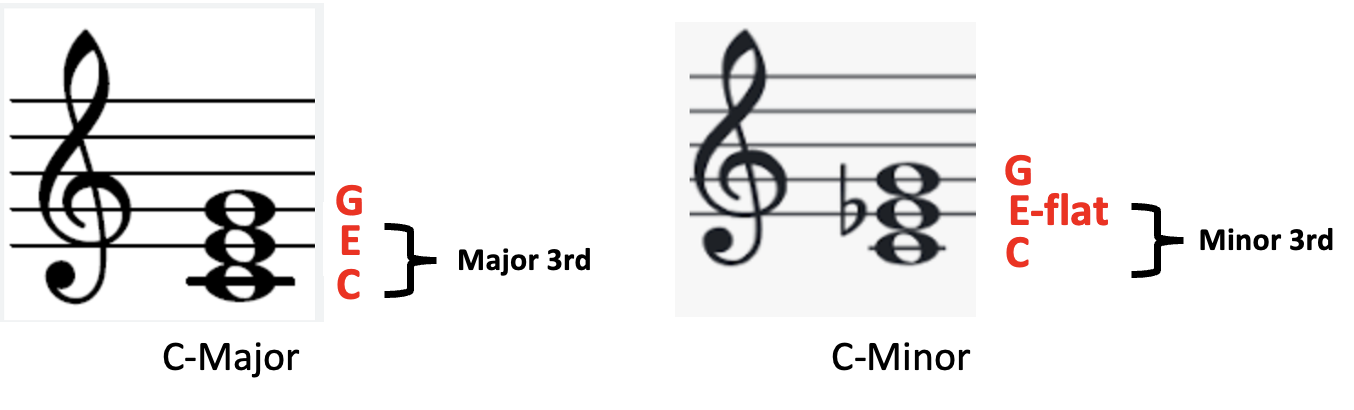

Now, let's sprinkle in some music theory. Consider two chords, C-major and C-minor:

C-Major and C-minor chords differ by only one-half note – E and E-flat. A small difference with a big impact. The difference in sound is due to the interval between the two lowest notes: a major third (C to E, three notes between them) and a minor third (C to E-flat, two notes between them).

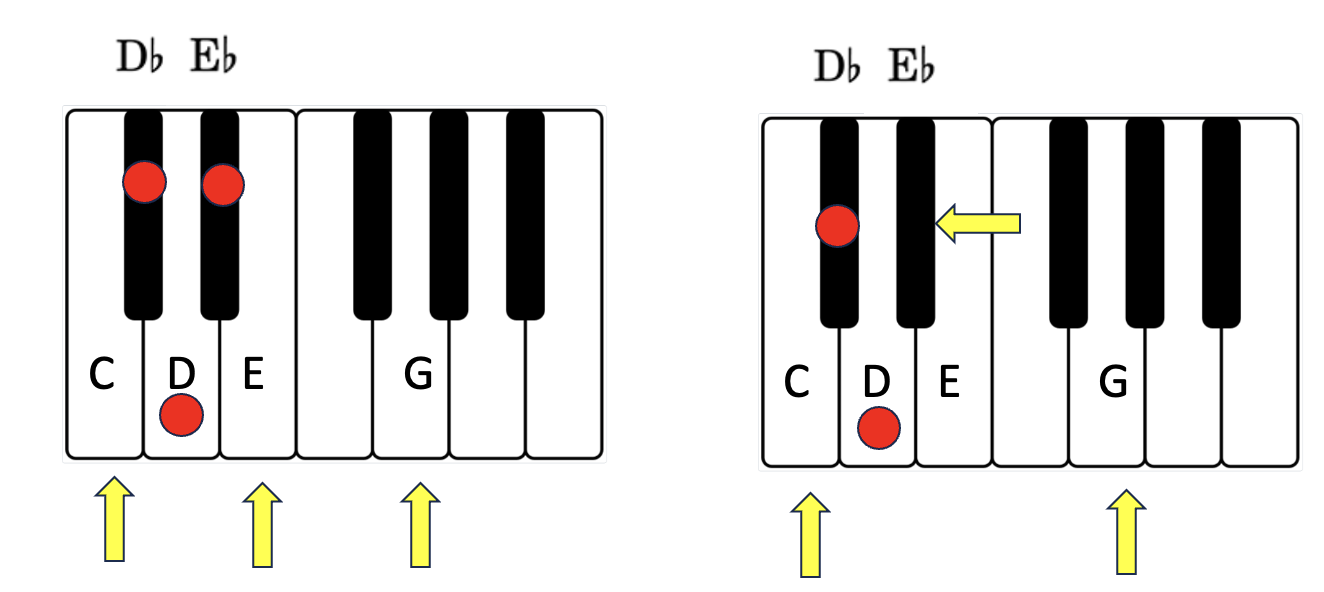

Here it is on a piano:

Figure 1. (Left) A C-major chord (yellow arrows) consists of C, E, and G. Note that the chord begins with a major third – three half-notes, aka semitones, (red dots) between C and E. (Right) In a C-minor chord the interval between C and E-flat is a minor third – only two half-notes between the two. This difference – E being higher than E-flat – is thought to be responsible for the brighter sound of a major chord.

A small, but significant difference

Now, let's consider a small yet significant difference: The difference in the frequencies of the lowest and highest notes on the piano amounts to 4,159 Hertz. In comparison, the difference between E and E-flat (above middle-C) is a mere 19 Hertz—a seemingly negligible number, but one with substantial consequences. This distinction should be evident even to those who don't understand or appreciate music.

To illustrate this point further, let's examine two examples of Chopin's famous Funeral March. I played a few measures of each, one in C-Minor and the other in C-Major. The first should be immediately recognizable. The second one just sounds weird.

Nature or nurture?

The debate over whether our perception of music and emotion is solely a product of learned experiences or has roots in our inherent biology is probably unsolvable. According to one perspective, our exposure to music in various media forms, such as movies and television, reinforces certain emotional associations. For instance, the prevalence of minor chords in soundtracks accompanying scenes of sadness, like the death of a family member, may condition us to link minor chords with feelings of melancholy (1). However, I propose that there may be deeper underlying factors at play. Why did this association emerge initially? Can it be attributed solely to coincidence?"

A professional musician on the Quora site writes:

A minor 3rd doesn’t occur until the 19th [multiple] (this means 19 Hertz), a minor 3rd above the 16th harmonic [for example C and E-flat]. Our ears perceive it as less sonorous than a major 3rd because of the weaker relationship between the frequencies.

Another professional musician writes on Reddit:

Harmony and its functionality are coming directly from nature, from some natural math, and the human brain has been exposed to it from the beginning. I'll let a scientist take it from here.

And a music professor posted an intriguing theory on Quora:

When you are an infant, or even before you are born, you hear your mother’s voice. If she is happy and contented her voice is low and serene and it reinforces the lowest partials in the harmonic series resonance of her voice. The first five partials (half notes) of the harmonic series spell a major chord.

Can there also be a biological basis for the difference in the perception of major and minor chords? Some scientists say yes.

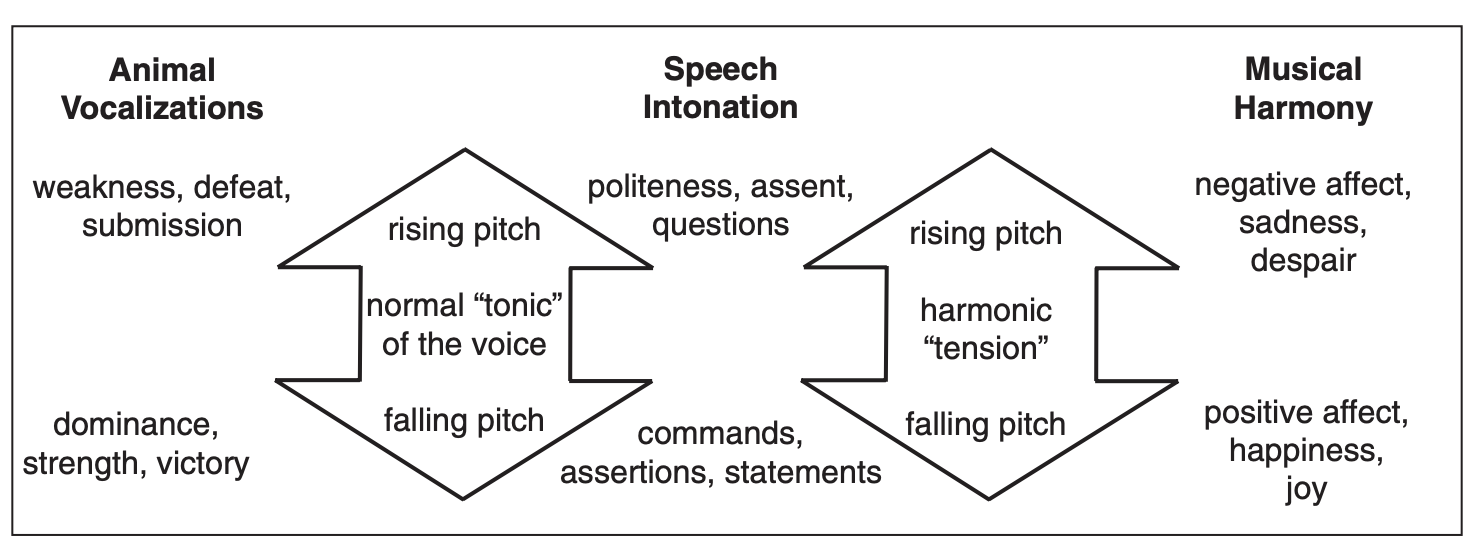

For example, Dr. Norman Cook, writing in Proceedings of The First International Workshop on Kansei (in case you missed it) that these perceptions are related to both animal and human communication:

Without exception, a semitone increase in pitch leads to a minor chord and a semitone decrease leads to a major chord. Questions concerning harmonic affect can then be rephrased as: Why does a decrease in pitch from a state of harmonic tension imply positive affect, whereas an increase implies negative affect? The answer is already known from the “sound symbolism” of human languages and animal vocalizations: decreasing vocal pitch is used to indicate strength and social dominance (commands, assertions), whereas increasing pitch signals defeat and social weakness (questions, uncertainty). The affect of major or minor chords is thus inherently positive or negative because the tonal structures have ancient evolutionary implications of high or low social status.

Cook, "A Psychophysical Explanation for Why Major Chords are “Bright” and Minor Chords are “Dark”

ChatGPT is helpful in simplifying the above paragraph:

When sounds go up, they usually make us feel a bit sad, like in minor chords, and when they go down, they often make us feel happier, like in major chords. This happens because our brains have learned from language and animal sounds that going down in pitch shows strength and confidence, while going up signals uncertainty or weakness. So, major and minor chords can make us feel positive or negative based on how the pitches move, echoing ancient feelings of social status.

This suggests that biology and probably evolution play a part in our reactions to different musical sounds.

Cook illustrates this in Figure 2, below.

Figure 2, The relationship between rising and falling pitch in major and minor chords on animal and human communication and human emotion. Source: Cook, The Sound Symbolism Of Major And Minor Harmonies, Music Perception, Volume 24, Issue 3 3; February 2007

If you didn't understand Cook's first quote, good luck with his conclusion:

As a consequence, when a 3-tone combination shifts away from the unresolved tension of intervallic equidistance toward harmonic mode, we infer an affective valence from our detection of the direction of tonal movement. This, I maintain, may be the biological origin of the affect of major and minor harmonies.

The translation of all of this (at least to the degree that I can understand) is that major and minor chords serve a purpose in animal and human communication, which may be why they elicit such differences in emotion. In other words, our perception of sad and happy chords is part of an evolutionary process rather than simply a conditioned response.

Hopefully, all who managed to make it through this will not be conditioned to avoid my future writings. As a reward, here's a special treat: One of the world's finest pianists playing what is widely considered to be the best piece of music ever written. Spend 11 minutes. You'll thank me.

NOTES:

(1) In some cultures, the descriptions of the two sounds are reversed.

(2) ChatGPT: "Tension triads" is a term used to describe certain types of chords that create a sense of tension or instability in music. These chords typically contain intervals that produce a dissonant or unsettled sound, which can create a desire for resolution to a more stable chord. (I wrote about something like this in 2016. See Different People Hear Music Very Differently)