Commercial insurance, that employer-provided benefit, initially a workaround to World War II price controls, provides most health coverage to Americans. In 2018, this insurance covered a third of health care spending, for 57% of the “nonelderly” population, about 153 million of us. Government-funded programs, Medicare and Medicaid, fulfill that role for most remaining Americans, leaving 8.5% paying entirely out of their pocket.

The study used claims data supplied by self-insured employers, state-based all-payer claims, and health plans that participated in the research, covering hospitalizations and physician costs from 2016 to 2018. To make the analysis more manageable, they combined those payments, which are customarily paid separately. The claims covered all sites of care and, while not comprehensive, should give us a reasonable picture.

While the Rand researchers presented their results as both standardized and relative differences, I am reporting the relative difference. They are easier to understand and capture many of the nuances of Medicare payments, like adjustments for regional pay scales, the intensity of service, costs for medical education, and otherwise uncompensated care.

“Price variation is expected in a market as complex as health care.”

- Commercial insurance pays more than Medicare for the same services.

- In the three years of the study, commercial insurance payments rose from 224% of what Medicare would have paid to 247% in 2018.

- In dollar terms, over those three years, commercial insurance paid $33.8 billion for those services. Services, at Medicare rates, would have been $14.1 billion, a potential 58% savings.

- The relative differences varied quite a bit. Commercial insurance paid 227% for inpatient care, 284% for outpatient care, and 165% for physicians’ care

- Rates varied between states, e.g., Arkansas less than 200%, Florida 320%. And the variations were just a wide within states and even within hospital “systems,” where the top hospital in a system would receive 32% more than a bottom hospital

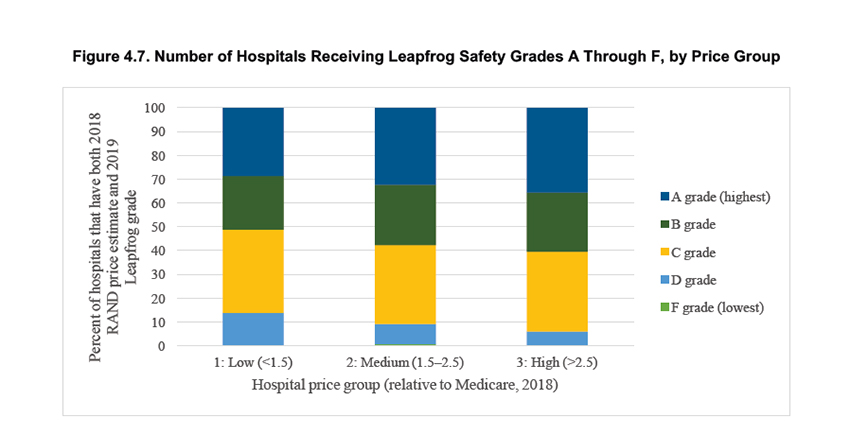

The researchers also compared price versus quality using two metrics; the CMS star ratings for hospitals and the Leapfrog group safety metric. Both measures have their proponents and detractors, both are imperfect, but in different ways.

- The good news, high-priced hospitals had better star ratings – 20% of the most expensive had five stars, but 4% had only 1 star.

- The lowest-priced hospitals fared more poorly; only 2% had five stars, 1% had only 1 star.

- In between were the “Goldilocks” hospitals, where quality and cost were optimized, creating “value,” for example, 91% of those low-price hospitals had three or more stars.

- While the analysis was incomplete concerning hospitals, safety, or “all the outcomes that health care purchasers value, such as patient convenience and hospital reputation,” their study “does not show a clear link between hospital price and quality/safety.”

Why are there such price variations?

While there are regional differences in the cost of living, much of that is accounted for in Medicare payments. And if there is a relationship between cost and quality, as measured by those stars or grades, it is not strong. Some experts have argued that the price differences reflect cost-shifting as commercial insurance pays more to make up for Medicare payment “shortfalls.” Others have argued that hospitals leverage their geographic reach and number of unique “lives covered,” to extract greater payments. Perhaps that is why physicians, who remain, by and large, small practices or employed physicians without organized representation show the least difference in payments.

The researchers take a more practical approach, saying, “these competing explanations are largely abstract.” The only question is whether these higher prices are reasonable and necessary – shortfalls are not their problem. Now some of this is a bit of externalization. Shortfalls, if they do indeed exist, may result in hospitals closing, reducing services or access, events that are not in the interest of insurance beneficiaries, that would be you and me.

They ultimately take a different tack, pointing out that 35-43% of all services “are potentially shoppable.” Shoppable, of course, doesn’t apply to emergency care. It also does not apply to the bulk of hospital admissions to treat medical diseases, like cancer or pneumonia or a stroke. To be shoppable, it needs to be common, a commodity rather than tailored care, researchable in advance, therefore elective, with many providers creating competition, and of course, price transparency. I use providers here because, at this level of analysis, physicians, my preferred term, simply provide a commodity and are reduced to full-time equivalents on spreadsheets.

When you dig into that 35-43% estimation, it refers to elective surgery, and your choice of health system, site of service, and providers. Those are a lot of variables, and even with price transparency, choosing can be burdensome on patients. Navigating the tradeoffs in terms of convenience, follow-up, safety, at the lowest price, is a challenge. The insurance companies seek to lessen this cognitive load in several ways. They create narrow networks of providers, asking you to trust that they have done the calculations in your favor. Alternatively, they may establish reference pricing where the health plan indicates what it will pay for the service, and you spend or save the difference by your choice.

All the players in the drama distort the system. We want the biggest bang for the buck, and that means the best, safest care at the least price. The insurance companies want satisfactory care at a reasonable price. By law, they must spend 80% of their revenue on medical care; the remaining 20% is administrative and other expenditures. So higher costs become greater administrative expenditures for salary and benefits.

The difference between commercial payments and those of Medicare shine a light on what is meant by Medicare-for-all. The discussion is how to spread out the costs of health care most equitably. Price transparency will help but distracts from the real question; how to share the costs. Are we our brother’s keeper? Does it matter that they have bad habits? Why should I have to pay for you as well as me?

Source: Nationwide Evaluation of Health Care Prices Paid by Private Health Plans