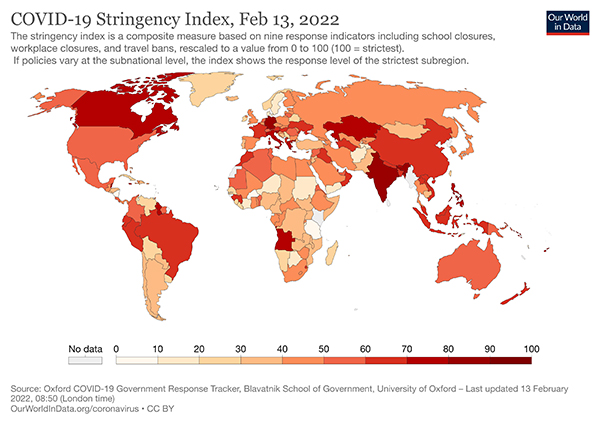

Lockdowns, non-pharmacologic interventions, and that includes wearing masks have been a feature of our lives for well over a year. We are not alone as the Hopkins study reports of the 186 countries studied all but one imposed restrictions. Here is the current global situation based upon a “stringency index.” [2]

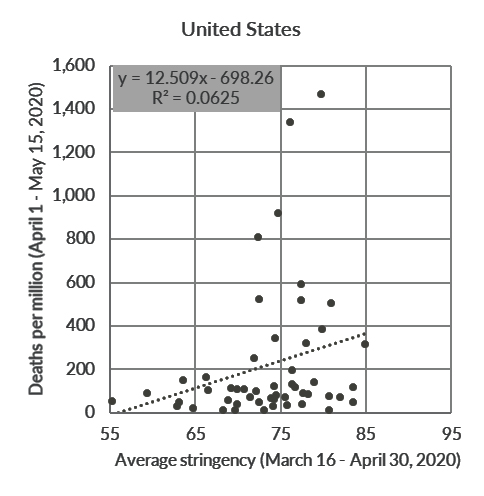

The researchers were spurred to do the analysis because there did not seem to be a significant correlation between the stringency of lockdowns and the reduction in fatalities.

Let’s pause for a moment. Deaths do seem like a reasonable outcome to measure. But deaths are the “product” of the prevalence of the virus, those that are susceptible, those adhering to the lockdowns, and the quality of the care available, among other factors, so deaths are not a perfect measure.

"Today, it remains an open question as to whether lockdowns have had a large, significant effect on COVID-19 mortality.”

To address that issue, they considered mandated behavior, not access to testing or voluntary vaccination, just required behavior. This definition is a bit confounding because any of us who has driven over the speed limit knows what is mandated and what is done often varies. More importantly, in many instances, people who felt at risk from COVID-19 restricted themselves long before the government required it.

They restricted their search to articles that attempted to establish a relationship between “lockdowns” and mortality. They identified 39 studies that they went on to analyze. The choice of studies is always an “Achilles heel” for those that wish to argue the findings. Many of the studies that the “experts” felt should have been included involved modeling excess deaths or mortality, not actual numbers. You can decide whether that is “cherry-picking” or not.

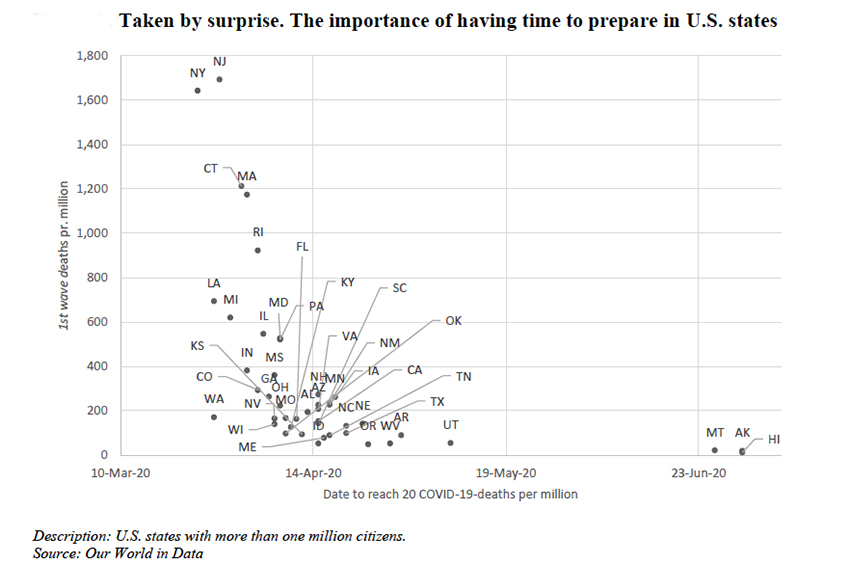

Closing the door after the horse leaves the barn

They excluded studies done early in the pandemic. As they write,

"There’s no doubt that being prepared for a pandemic and knowing when it arrives at your doorstep is vital."

Remember the late winter of 2020 and the shock of so many deaths in New York and New Jersey. They literally did not know what hit them, which shows in the mortality data. As we learned more and began to take a range of medical treatments along with those “lockdowns,” we improved. So let us begin with the first of the critical but overlooked messages, when to apply (and end) lockdowns is more art than science. Given the institutional inertia we have all seen, it is no wonder that lockdowns were instituted or ended later than hindsight would suggest.

A diversity of sites, times, and measures

The researchers go on to catalog their chosen studies. Essentially all look at COVID’s first wave, some in Europe, some in the US. Some looked at stay-in-place orders; others looked at more stringent mandates; others considered all the mandates an aggregate, others separately. Some studies demonstrated a negative correlation of deaths with lockdowns, others a neutral effect, and still others a positive correlation. Diversity is good; it broadens the field of consideration. But diversity makes statistical conclusions a bit more suspect; given enough variables, I can conclude whatever I want.

The impact of increasingly stringent mandates

“Compared to a policy based solely on recommendations, we find little evidence that lockdowns had a noticeable impact on COVID-19 mortality … Indeed, according to stringency index studies, lockdowns in Europe and the United States reduced only COVID-19 mortality by 0.2% on average.”

We could, as some media have reported, just used the last phrase of that quote. Of course, we would have left out the initial caveat; this was the impact of being mandated rather than recommended. The effect of a voluntary change in our behavior is lost in that number. More importantly, unless you read the actual study, you would not know that the 0.2% is weighted and that for the same studies, the median reduction was 2.4%. The arithmetic average reduction was 7.3%. Which number tells THE truth?

The impact of shelter in place orders (SIPO)

This data was more of a hot mess. SIPO were rarely instituted without similar mandates for schools and businesses. And SIPO was instituted a week or more after the school and business mandates. Some called for the closure of all non-essential businesses, others for a few non-essential businesses. This doesn’t even consider the definition of essential, like GNC in New York.

"We find no clear evidence that SIPOs had a noticeable impact on COVID-19 mortality. … The overall effect measured by the precision-weighted average is -2.9%.”

Of course, “little evidence” referred to the reduction of 0.2% for stringency measures. “No clear evidence” refers to the nearly 15-fold greater percentage for SIPO. Overlooked message number 2, words do not always convey the meaning of numbers.

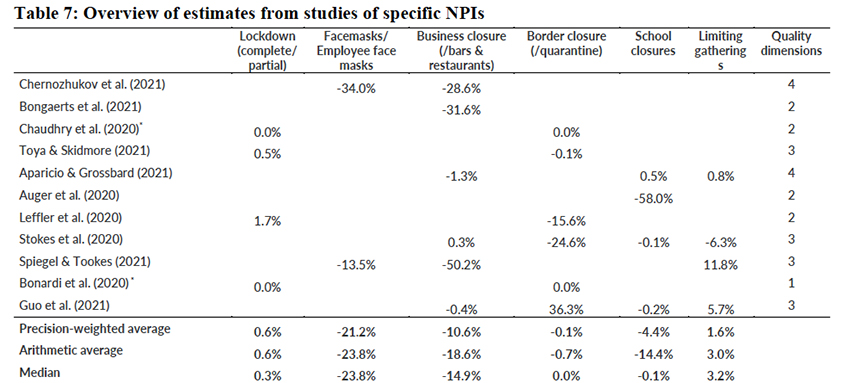

The impact of specific non-pharmacologic interventions (NPI)

Again, given the studies, the definition of these NPIs varied. For example, some governments required everyone to wear masks, other mandated masks for specific employment. Definitely apples and oranges.

"Because of the heterogeneity in NPIs across studies, it is difficult to draw strong conclusions based on the studies of multiple specific measures. We find no evidence that lockdowns, school closures, border closures, and limiting gatherings have had a noticeable effect on COVID-19 mortality. There is some evidence that business closures reduce COVID-19 mortality, …and the effect seems related to closing bars. There may be an effect of mask mandates, but just two studies look at this, one of which one only looks at the effect of employee mask mandates."

Here are their findings in table form. There is something for everyone on either side of the partisan divide. Masks seem to help, although there are only two studies, so does the closure of some businesses that emphasize the social – bars and restaurants. Closing borders, no impact at all. School and limited gatherings, I would say dealers' choice. And remember, these reductions are from the first wave, not Delta or Omicron. Both variants have very different impacts on mortality and might significantly alter these findings.

From the discussion

"Overall, we conclude that lockdowns are not an effective way of reducing mortality rates during a pandemic, at least not during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. ...

Our main conclusion invites a discussion of some issues. Our review does not point out why lockdowns did not have the effect promised by the epidemiological models of Imperial College London (Ferguson et al. (2020). We propose four factors that might explain the difference between our conclusion and the view embraced by some epidemiologists."

- "People respond to dangers outside their door" – that is, we respond to our perception of danger, and we respond far sooner and longer than what the government mandates. That holds equally true for those compliant and non-compliant.

- "Mandates only regulate a fraction of our potential contagious contacts and can hardly regulate nor enforce handwashing, coughing etiquette, distancing in supermarkets, etc." Once again, there is our personal behavior at play.

- "Even if lockdowns are successful in initially reducing the spread of COVID-19, the behavioral response may counteract the effect completely, as people respond to the lower risk by changing behavior.” Damn humans

- "Unintended consequences may play a larger role than recognized. …often, lockdowns have limited peoples’ access to safe (outdoor) places such as beaches, parks, and zoos, or included outdoor mask mandates or strict outdoor gathering restrictions, pushing people to meet at less safe (indoor) places.”

When you look at those four factors, they are just variations on one, our individual assessment and response to risk, to ourselves and others.

You have to read until the end

After 64 pages, who has any desire to read the supplements. But hidden there is overlooked message 3, “voluntary behavior changes are essential to a society’s response to a pandemic and can account for up to 90% of societies’ total response to the pandemic." The researchers only looked at the mandates. They really found that our behavior, individually and then in aggregate, may be markedly different from what the government mandates. But anyone who has gone over the speed limit, driven a car while “buzzed,” or has inflated their deductions already knows that.

For those of you who made it this far, and I suppose I am preaching to the choir – can you see why this study cannot be summarized in a soundbite or meme? You undoubtedly do not have time to read the study, but you should search for more than a quote or a click-bait headline.

[1] That is one of the big perks of this job; I get paid to read some interesting studies. The article's writing is often just the tip of the iceberg. The reading of primary documents and context is the greater part of the labor.

[2] The index, formally the Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) stringency index, uses nine metrics, school closures; workplace closures; cancellation of public events; restrictions on public gatherings; closures of public transport; stay-at-home requirements; public information campaigns; restrictions on internal movements; and international travel controls. Higher values are more stringent.

Sources What You Need to Know About That 'Johns Hopkins' Lockdown Study MedPage

A Literature Review And Meta-Analysis Of The Effects Of Lockdowns On Covid-19 Mortality