“Everybody knows” that America is undergoing a public health crisis in addiction and death involving opioids. Many media sources -- and even some medical doctors who should know better -- have attributed the causes of this crisis to “over-prescription” of opioids by clinicians to their patients. However, this explanation for our public health crisis is factually wrong. Data published by authoritative sources including the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention prove that it is wrong.

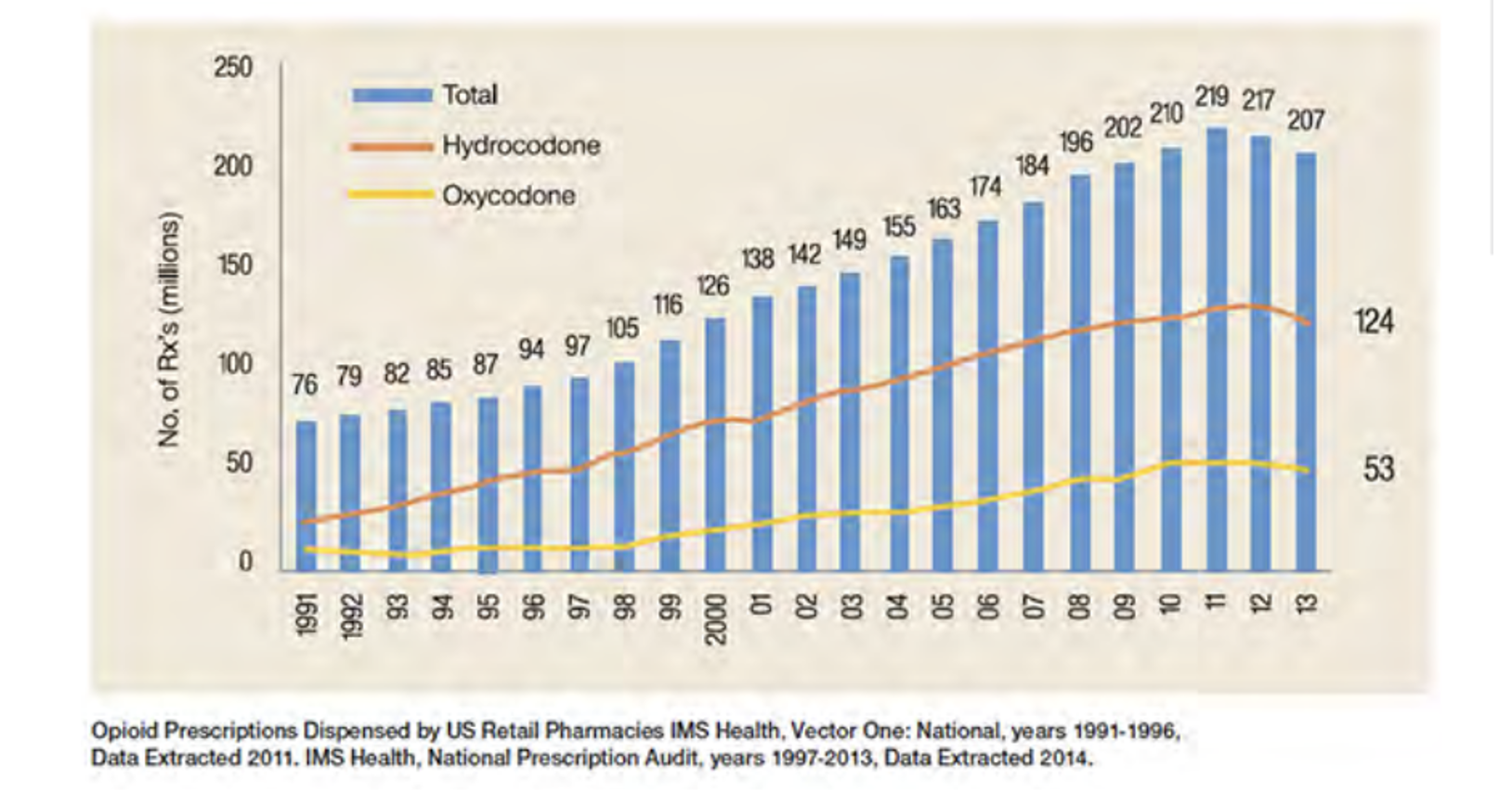

Opioid prescribing grew steadily from 1980 to 2011. Figure 1 shows numbers of prescriptions recorded for two high-volume prescription drugs over this period.

Figure 1: Prescriptions for Oxycodone and Hydrocodone, 1991-2012

Part of this growth can be attributed to a few doctors and pharmacists who operated pill mills, often serving walk-in clients who shammed pain-related illness in order to obtain opioids for resale in street markets.

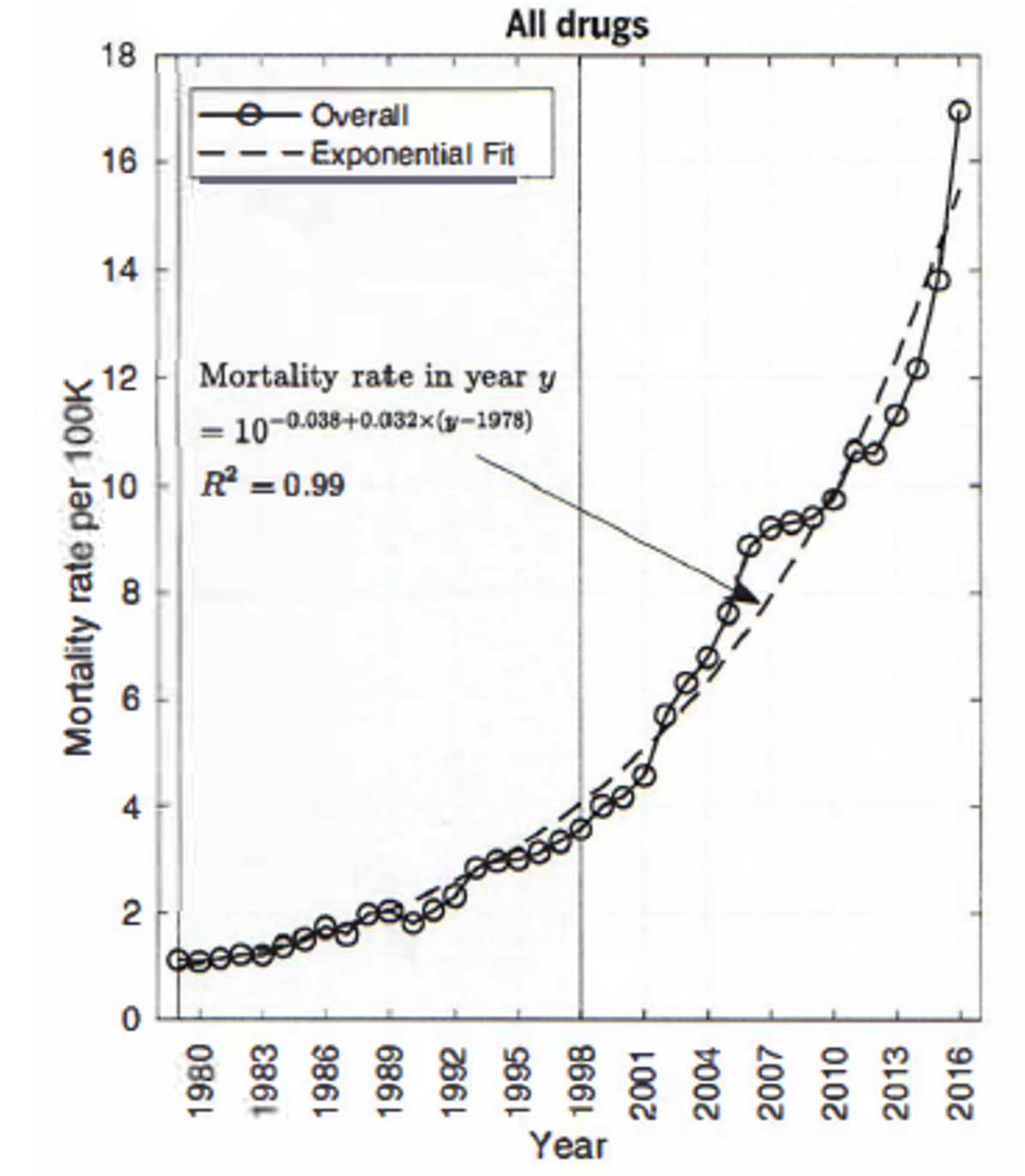

During this period, opioid overdose-related deaths also grew, with a very different trend curve:

Figure 2: Drug-Related Mortality Per 100,000 Population, 1980-2016 (all drugs)

Source: Hawre Jalai, et al, “Changing dynamics of the drug overdose epidemic in the United States from 1979 through 2016”, Citation: Science, 361, eauu1184, (2018). DOI: 10.1126/science.aau1184.

Also cited by Chuck Dinerstein in “The Overdose Epidemic in Three Pictures” American Council on Science and Health, September 20, 2018 https://www.acsh.org/news/2018/09/20/overdose-epidemic-3-pictures-13424

Figure 2 shows the composite curve of mortalities from all accidental drug poisoning involving Heroin, Methadone, synthetic opioids other than Methadone, Cocaine, Methamphetamine, unspecified narcotics, unspecified drugs generally, and prescription opioids. Contributions to mortality from these “sub-epidemics” vary sharply over time and between US States.

Even near the height of the pill mill sub-epidemic in 2008, deaths from prescription opioids ranked sixth – lower than unspecified narcotics, unspecified drugs generally, Methamphetamine, Methadone, and Heroin. The contribution of prescriptions made by clinicians to legitimate patients throughout the period 1999 to 2019 were literally so small that they got lost in the noise of street drugs and uncertainties in the attribution of deaths by medical examiners and coroners across the US.

It must also be remembered that drugs dispensed by pill mills were still “prescription” drugs. Even when abused for non-medical purposes, such drugs are still of known doses and were significantly safer than illegal street drugs of unknown composition. Thus there is substantial reason to believe that dominant public narratives blaming the opioid crisis on doctors “over-prescribing” to their patients – or even doctors operating pill mills – are substantially unsupported by the available data.

Working independently of Hawre, et al, the author has also analyzed opioid mortality statistics, arriving at closely similar conclusions. See Richard A Lawhern, Ph.D. “One Opioid Epidemic or Many?” American Council on Science and Health, May 14, 2018. https://www.acsh.org/news/2018/05/14/one-opioid-crisis-or-many-12956

Four events during 2010-2012 had major impacts on legitimate prescribing, without substantially altering the exponential rise in overdose mortality.

- US FDA-mandated reformulation of Oxycodone into abuse-resistant form in 2010 caused prescription rates for this drug to immediately drop, even as deaths from street Heroin tripled in three years. However, overall deaths from prescription drugs remained level.

- Six US States created state-administered Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs). Volumes of opioids prescribed by pill mills became more visible to law enforcement. “Patients” who doctor-shopped with multiple medical providers also became more visible.

- US Drug Enforcement Administration belatedly began prosecuting operators of pill mills. Unfortunately, DEA also mounted a witch hunt against many conscientious clinicians whose only crime was taking on patients who had lost their pain doctors due to the actions of the DEA itself.

- Starting in 2012, increasing numbers of overdose deaths involved illegally imported Fentanyl and its analogs. By 2019, the fraction of opioid poisoning deaths attributable to Fentanyl rose to at least 80%.

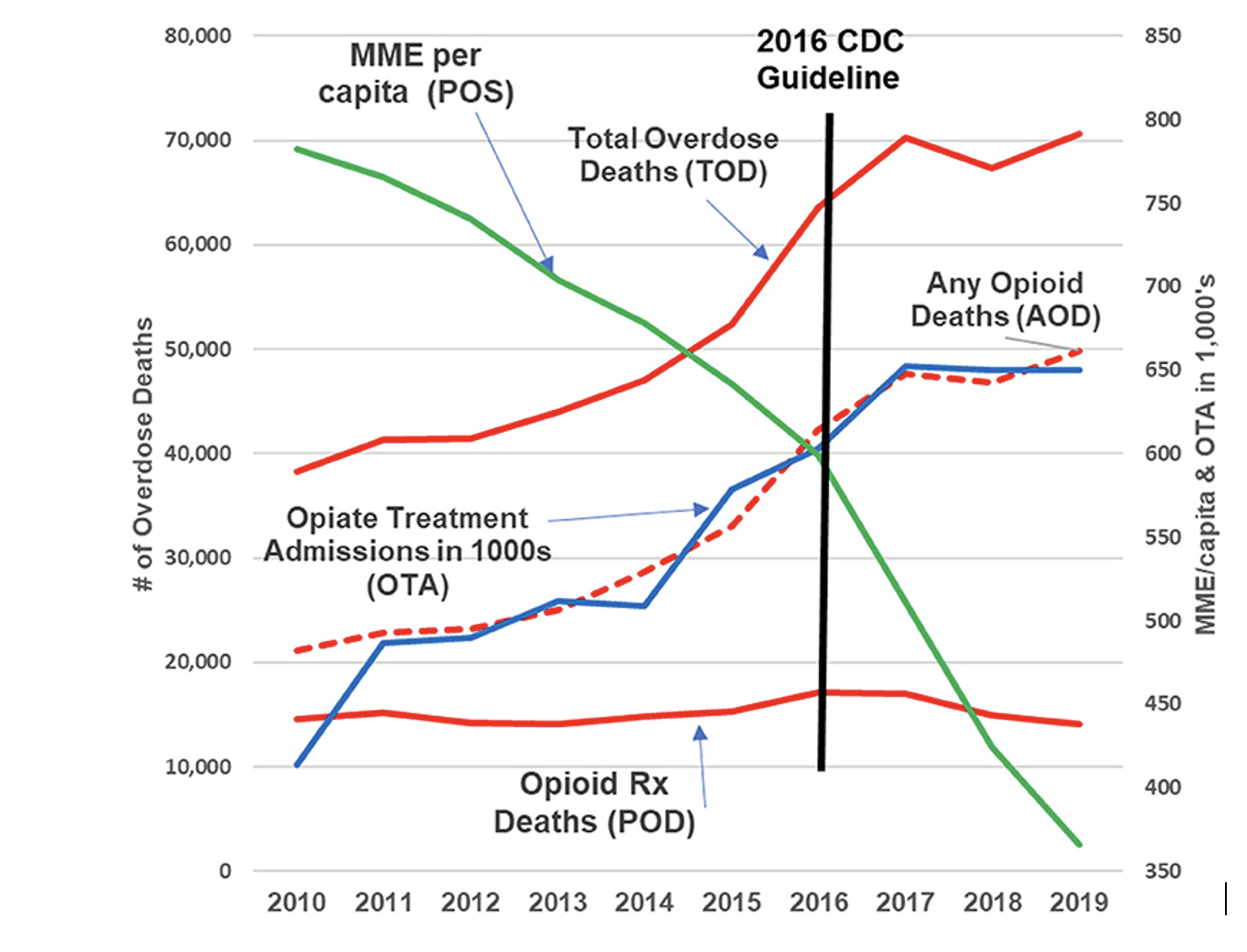

From 2010 to 2019, responding to both the crackdown on pill mills and the overshadowing effects of law enforcement prosecution of doctors who prescribed opioids to legitimate patients, the total volume of opioid prescriptions dropped by 60%. Deaths in which a prescription opioid was one factor remained steady at around 15,000 per year. However, total overdose-related deaths continued to climb exponentially.

In an independent reanalysis of drug poisoning deaths and hospital admissions for treatment of opioid toxicity, Larry Aubry and B. Thomas Carr concluded in 2022 that despite US CDC assertions to the contrary, there has been no cause-and-effect relationship between rates of prescribing versus either rates of hospitalization or rates of opioid-related overdose mortality, since at least as far back as 2010. As noted above, there is also reason to doubt that prescribing by doctors contributed significantly even at the height of pill mill operations between 2001 and 2010.

Figure 3: Opioid-Related Mortality and Opioid Treatment Hospital Admissions, versus Volume of Prescribing in Morphine Milligram Equivalents, 2010-2019

Source: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpain.2022.884674/full

Conclusion:

It is apparent from widely published data that America’s opioid “crisis” is multi-factorial and highly dynamic. However, as concluded by multiple investigators – and as known for years by both the US CDC and DEA – “Today’s nonmedical opioid users are not yesterday’s patients.”

[Source: Jeffrey A. Singer, Jacob Z Sullum, and Michael E Schatman, “Today’s nonmedical opioid users are not yesterday’s patients; implications of data indicating stable rates of nonmedical use and pain reliever use disorder” Journal of Pain Research 2019, 12, 617-620, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6369835/ ]

It is thus glaringly obvious that the emphasis of November 2022 CDC opioid prescribing guidelines on risks of opioid addiction and mortality among patients managed by clinicians is vastly over-hyped, scientifically unsupported and ethically inappropriate. The open question is how to correct course. The author offers the following insights.

- The current misdirected regulatory climate for pain clinicians has driven thousands of doctors and treatment centers out of practice, deserting millions of patients to agony. To correct this state of affairs, clinicians need a balanced and scientifically based practice standard within which they can be assured that they will not be sanctioned, denied clinical privileges, or arbitrarily prosecuted for mythical "over-prescribing".

- Pain treatment by clinicians must be individualized to patient needs and sensitive to the wide variability of genetically mediated patient drug metabolism and side effects.

Source: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpain.2021.721357/full

3. Opioid therapy is not the automatic first choice for all patients. But it is indispensable and mostly safe for many who are in moderate to severe pain, who do not respond to other therapies, or for whom such therapies are contra-indicated.

4. The central practice standard should be "When opioids appear to be needed, start at low doses and titrate to desired analgesic effect while monitoring and managing for disabling side effects. Treat for co-morbid depression and anxiety. Refer for indications of preexisting opioid misuse. If a satisfactory balance is not attained, transition the patient to other opioid medications and ancillary therapies.”

Source: https://www.futuremedicine.com/doi/pdf/10.2217/pmt-2022-0017

5. Deeply revised guidelines are needed but cannot be attempted by CDC or AHRQ -- both of which have both demonstrated a record of profound anti-opioid bias, bad faith and incompetence. US National Academies of Medicine likewise have not demonstrated competence in such a project.

Source: https://www.pallimed.org/2022/09/undisclosed-conflicts-of-interest-by.html

6. Political interference in the evidence-based treatment of pain must cease. Balanced treatment guidelines must instead be written in a publicly transparent process by clinicians who have hands-on experience in the community and/or hospital practice of pain management. Multiple medical specialties and practice environments must be represented. Patients and their advocates must also be represented in this process as voting members of any publication approval group. The process might resemble the HHS Inter-Agency Task Force on Best Practices in Pain Management, with participants nominated by the American Medical Association, American Academy of Family Physicians, and other medical professional associations

____________________________________

Author Note: In the coming weeks, the author will transmit this report to the Secretary of Health, Director of CDC, Director of the HHS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, and Director of the Drug Enforcement Agency, among others. Readers wishing to endorse the paper may do so by sending email to Lawhern@hotmail.com with their name, city, state, and clinical qualifications if any. I hope to have at least 100 endorsements by clinical professionals. Chronic pain patients are also welcome.