“It is the very error of the moon: She comes more nearer earth than she was wont, And makes men mad.”

- Othello, William Shakespeare

Could the moon influence our moods and behavior? It does, after all, influence our oceans. The researchers wanted to look at the effect of time on suicides. For that, they used data from the Marion County Coroner’s Office in Indiana, from January 2012 to December 2016. There were:

- 210 completed suicides within the week of the full moon

- 566 suicides outside the week of the full moon

- 208 individuals aged 30 years and younger, 232 individuals 55 years and older

- A subset of 45 cases had blood samples collected, 38 male and 7 female violent suicide completers

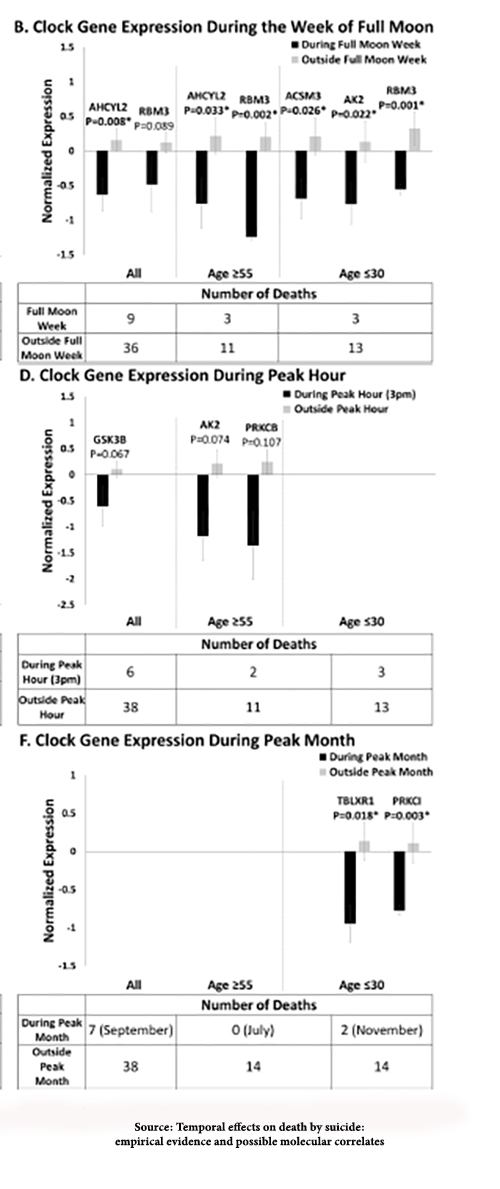

Let’s get the moon issue out of the way first. Suicides during the full moon were statistically greater for those over age 55 but not for those under 30. But the peak hour was between 3 to 4 pm. Additionally, September was the peak month for the over 55’s, and November for the under 30s.

Let’s get the moon issue out of the way first. Suicides during the full moon were statistically greater for those over age 55 but not for those under 30. But the peak hour was between 3 to 4 pm. Additionally, September was the peak month for the over 55’s, and November for the under 30s.

The researchers identified 1,468 genes with circadian functions, about 7% of our total genetic inheritance. Eighteen were the main circadian “engines,” while another 331 genes directly impacted the engines; the remainder influenced those 331 intermediary genes. They also identified 154 “biomarker genes” associated with suicides. Comparing the two groups, genes related to suicide and circadian genes, they found nearly a twofold enrichment among the suicidal genes with a circadian component. Moreover, they found changes in gene expression associated with suicide at the time of death.

Suicide is complex with clear psychological and now, more clearly, biological features. The researchers offered some possible reasons.

- “An increase in suicides during the full moon could be due to the moonlight affecting vulnerable individuals at a time when there should be dark.” They posit that those under 30 are more likely to be awake on their cell phones at night, reducing their exposure to moonlight. While they may be a “bridge too far” for some of us, circadian clock genes are “enriched” during this interval.

- The peak of suicides late in the afternoon may be related to “day of event stressors,” but that is when there is a lower expression of cortisol and several clock genes. The researcher point out that those genes were predictive of their findings.

- As to that September peak, “incidentally, coinciding with Suicide Prevention Month,” it is the end of summer, vacation, and the beginning of the school year and work in earnest. It is also the beginning of a change in daylight that presages seasonal affective disorder, a disease we know has a circadian component. For the under 30 whose suicides peak in November, we might posit “the holidays.”

Much remains unanswered by the study, and the researchers' narrative leaves me unsatisfied even though I am more than willing to believe that our biology can and does play a role. It is already clear that our circadian rhythms influence our mood and sleep. “The enrichment in, and putative involvement of, circadian clock genes in death by suicide” should give us pause and can raise questions about the interplay of our “will” and our genetic expression. The researchers are undoubtedly correct in saying the work opens “the door to therapeutic interventions, whether chronobiological or pharmacological.”

Source: Temporal effects on death by suicide: empirical evidence and possible molecular correlates Discover Mental Health DOI: 10.1007/s44192-023-00035-4