Big Money

According to a study in Circulation:

- $80 billion was spent on treating ischemic heart disease, 25% of the $320 billion spent on cardiovascular diseases in 2016.

- Public insurance covers 54% of those costs, private insurance 37%, and out-of-pocket spending the remaining 9%

The figures have not gotten smaller over time. While outpatient visits to the cardiologist may represent the greatest number of interactions, procedural care, cardiac catheterization, stent placement, or open heart surgery are the big ticket payouts. In 2020, as a cost-saving measure, Medicare allowed catheterizations and stent placement (percutaneous coronary interventions, usually termed PCI) to be performed outside the hospital.

The cost of running a cardiac cath unit in the hospital, with a hospital’s higher costs and 24-hour-a-day service, running an outpatient cardiac cath unit, with all the necessary staffing and equipment, can be far less. [1]

Medicare pays approximately $6,500 for the placement of a coronary stent as an outpatient in a free-standing ambulatory care facility and $10,600 for the same procedure performed in a hospital. The costs associated with those procedures include staffing, equipment, and the facility itself. Even when employing the same number of nurses and other physician extenders, a free-standing center can have lower staffing costs because they do not use full-time maintenance or security. More importantly, the cost of the facility is the rent, heating, and cooling; no surcharge is added to an ambulatory care facility to pay off the costs of 24-hour labor availability or expensive radiology equipment, emergency departments, or operating rooms.

Before 2020, hospital systems opened these less expensive ambulatory care centers but insisted they were part of the hospital’s “extended campus” and would be paid at hospital rates. The 2020 changes allowed entrepreneurial cardiologists to open their own centers, increasing their revenue with those facility fees – following the example of orthopedic surgeons and gastroenterologists.

Enter Private Equity

Private equity (PE) investors seek large returns on their investments, and for that, they take increased risk. PE is focused on profitability to the extent that standardized care and quality metrics aid in that quest they are supported. Their labor costs may be more or less, but any decrease in pay may be balanced against a set work schedule that doesn’t involve nights, weekends, and holidays. The bottom line for PE is enhancing productivity – more volume means more revenue for the same costs – in econ speak, increasing marginal returns.

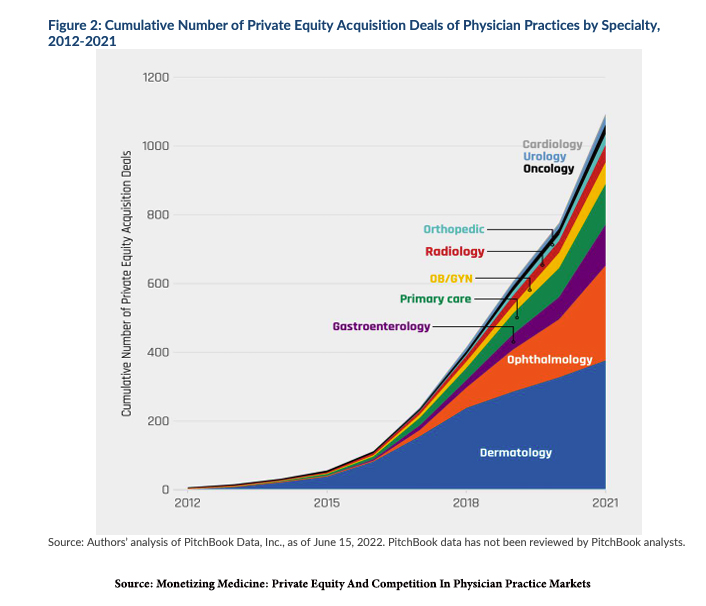

PE now owns 15 “platforms,” management companies that own or control orthopedics surgical groups. 10% of all gastroenterologists in the US work for PE-owned medical practices. Here is a visualization from the Petris Center at UC Berkeley, an economic think tank, and the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, a left-leaning think tank.

As you can see, cardiology groups are following the pattern set in acquiring orthopedics and gastroenterology. Currently, 10 management companies are buying up cardiology practices, and that number is expected to grow.

One of the key influencers in Medicare’s 2020 payment decision was Tim Attebery, DSc, MBA. As Stat reports,

“As head of the American College of Cardiology, Attebery wielded his power to help convince Medicare to cover artery-opening coronary procedures in outpatient settings. He said he signed a letter to the agency and met with then-administrator Seema Verma several times before the 2020 rule change. …Just a few years later, he heads one of the private equity-backed companies capitalizing on the change.”

Deal with the Devil

Undoubtedly, for many cardiologists, the majority of whom are already working for health systems, the possibility of working for a PE company has advantages. There is the infusion of capital to develop autonomous facilities and allow cardiologists to again be “their own bosses,” sort of. And there is the lure of both a short-term windfall as the practice is purchased and a long-term hope for a gain on the equity provided.

In the words of Mr. Attebery,

“As time goes on, of course, the goal is future liquidity events—what we call that second bite of the apple. And a third bite of the apple will eventually come, and a fourth. Our game plan is for cardiologists to become a part of this larger company and build wealth for themselves by providing value and taking care of patients. Ultimately, maybe this all leads to a deal between Cardiovascular Associates of America and an even larger private equity firm. Or maybe another strategic buyer will come along, or maybe we will eventually go public.”

Of course, one must remember that the first individuals in line for the liquidity events are the private equity investors; the cardiologists will get, as Tom Wolfe described in Bonfire of the Vanities, “the golden crumbs.”

More disturbing is what the patient will receive. To be fair, we do not know how these ownership changes will impact cardiology patients. But we see the impact on orthopedic and gastroenterological patients, and PE is playing with the same playbook.

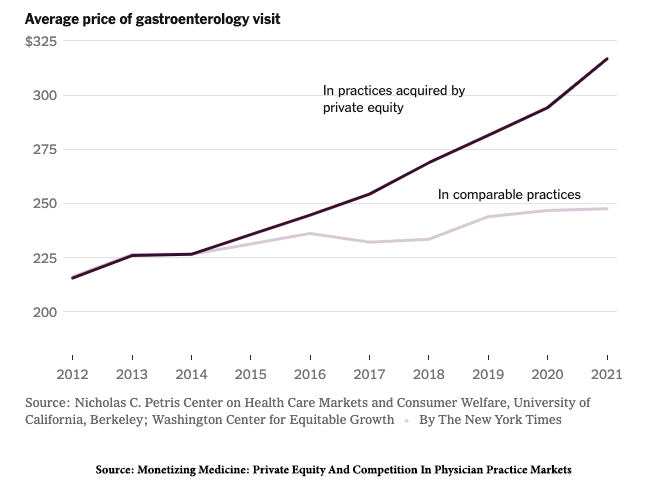

In roughly 25% of the US, PE-managed medical practices control 30% or more of the patients within the catchment area. That allows them to raise prices, as this graph demonstrates from the data of those two previously mentioned think tanks.

In a JAMA Network Open study, PE-owned firms increased their billing by 20% by seeing more patients at greater healthcare needs than matched controls. A review of PE management in gastroenterology noted

“The effects of PE ownership in gastroenterology are only recently being studied. Notable conclusions include increased costs of services, more visits by new patients, and increased esophagogastroduodenoscopy utilization absent any increase in total number of polyps or tumors removed. … To increase revenue, one needs to increase either prices or volume of services provided, and it appears as if PE-backed practices are effectively doing both. … the real question is whether there are improved outcomes resulting from this more expensive care delivery…” [emphasis added]

And that, my dear readers, is the million-dollar-plus question.

[1] The cost of maintaining a unit in a hospital requires the sharing of many labor and equipment expenses that are not directly used by the unit. A cardiac cath unit may be allotted some of the cost of 24-hour radiology services and equipment, along with hospital security, heating, and cooling costs.

Source: Experts fear private equity will pour gas on cardiology’s overuse problem, Stat

Monetizing Medicine: Private Equity And Competition In Physician Practice Markets American Antitrust Institute, in collaboration with the University of California at Berkeley Petris Center on Health Care Markets and Consumer Welfare, and the Washington Center for Equitable Growth