Alabama’s recent decision holding that embryos are considered children (albeit undone by the state’s legislature, but still regarded as valid in other states) reflects the current views of some legislatures, judges, and portions of society. Sorely contested by those who view human life as beginning at birth (not at conception), the IVF decision derives more from personal beliefs and outdated law rather than current legal modes of analysis.

Using a hard, legal approach, two schools of thought might apply:

- What is in the best interests of the child (whenever that status is achieved)?

- Should we give primacy to preserving life - any life, versus focusing on the interdiction regarding terminating life?

A third perspective is religiously driven. These religiously generated views may trample on legal constructs, violating the constitutional imperative of separating church and state [1], and surely affect legal outcomes.

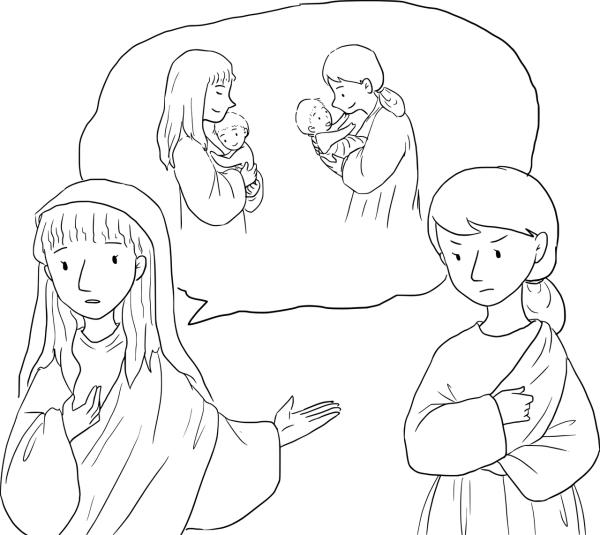

Let’s compare the differing reasoning and outcomes generated in two cases, which, while not exactly analogous to the IVF situation, illustrate conflicting religious views involved in decisions affecting perpetuating life.

Both cases involved conjoined (Siamese) twins; both were born with a shared 6-chambered heart, with one twin sustaining the life of the other ( weaker) one. In the American case, the weaker child was called Baby A. Her name was never given. In the British case, the stronger child was Baby A. Her name was Jodie. The question involved: was it permissible to perform surgery (separating the twins) that would surely kill (the word used was “sacrifice”) the weaker twin - Baby A in America and Baby B, named Mary, in Britain, so that the stronger child might live? The probability of survival of the stronger child was very small, at least in the American situation.

The British parents, devout Catholics, refused to allow the surgery. They were supported by Catholic authorities who ruled that one life cannot be sacrificed to save another. The physicians went to court to compel the operation; the parents sought a declaration that the separation surgery would be unlawful.

The British Court of Appeals (affirming the High Court ruling) held that the operation to separate the twins would be in the best interests of both children, [2] allowing Jodie to have a reasonably good chance of living a normal life and allowing Mary bodily integrity (presumably to die in peace). Secondarily, they based their decision on the double effect doctrine, [3] ruling that even though Mary’s death would be the inevitable conclusion of the surgery, it would not be the purpose of it.

Others disputed reliance on the double effect doctrine, using reasoning that might be applicable to the IVF situation where embryos are destroyed:

“[T]he 'evil' effect [killing one child] cannot be the means of achieving the good one, since we cannot condone an evil means to accomplish a good end (the ends do not justify the means).”

The Catholic Archbishop of Westminster, Cormac Murphy-O'Connor, England's highest-ranking Catholic, agreed with this reasoning, opining that separating conjoined twins violates the principle that human life is sacred so that no one should ever intend to cause an innocent person's death by act or omission. Indeed, Rev. Cormac Murphy-O'Connor advised the court that it would be better to do nothing at all, letting both girls die than to sacrifice one to save the other.

The British court would have none of it. Holding that the operation was mandatory, they reasoned that the anticipated (poor) quality of continued life for Mary would not justify withholding life from Jodie, guided by the ‘best interests’ principle.

In the American case, the Orthodox Jewish parents deferred to their sages. The physician in charge, Dr. Everett Koop, father of pediatric surgery and later to become surgeon general, was a religious Presbyterian (sometimes called a Fundamentalist) and devout opponent of abortion and termination of life. Nevertheless, he determined that surgery was necessary to possibly save the life of Baby B – even if it meant certain death for Baby A. However, he was not prepared to proceed without the approval of the parents and their rabbinical authorities. Even if that approval were forthcoming, Koop retained counsel fearing charges of murder, and the case was heard before a three Judge panel of the family court.

Dr. Koop’s initial personal stance, which espoused the sanctity of life, was illustrated by an earlier speech to the American Academy of Pediatrics entitled "The Slide to Auschwitz:"

"I fear the attitude of our profession is sanctioning infanticide and in moving inexorably down the road from abortion to infanticide, to the destruction of a child who is socially embarrassing….." -Dr. Everett Koop.

This view contradicts “official” Protestant views, described in another earlier conference:

“Protestant ethics seem to pose no obstacle to the surgical act; the disjoining act should be viewed more as a positive act of saving or preserving than as a negative act of destroying life. The emphasis is that life is more than quantity of days; that life is measured by quality as well as longevity.”

And yet, when it came to an actual case, Koop was determined that separating the twins was the proper course, advocating this position to a conflicted surgical staff:

“I can watch two babies die slowly over the course of several months, or I can watch one die swiftly and the other possibly live. No one likes to say, 'I'm going to kill one baby so that the other can live.'" -Dr. Everett Koop.

Since Baby A was kept alive through the extra work done by Baby B's heart, Koop viewed Baby A as a burden - even a parasite - and, as such, it was morally right to save Baby B by removing the parasite.

The Rabbinical authorities debated the matter for eleven days, with the leading Rabbinical sage, Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, advised by several Rabbinic scholars, including his son-in-law, Dr. Moshe Tendler, who was also an academic biologist, and his grandson, a physician. Two lines of reasoning were developed, one following Maimonidian logic, which considers Baby A as “pursuing” the life of Baby B and hence ineligible to be saved (echoing Koop’s rationale). The second line, closely akin to that followed by the court, reasoned that Baby A was already designated for death, akin to a parachuter on target for a safe drop who is permitted to cut the line of an interloper trying to latch on to his line, and who would otherwise die. In effect, the court and Rabbis ruled that saving one life with some, even remote, possibility of survival trumped the certainty of killing a child that would, at some point, surely die.

Koop waited for both religious and legal sanctions before operating. Both were received, although some Catholic nurses declined to participate in the surgery. In Britain, surgery was performed immediately after the court ruling. Mary died as expected, but Jodie survived – and is still alive as far as we know. In America, Baby A, as predicted, immediately died. Sadly, shortly after the surgery, do did Baby B

The British Judges agreed with their American peers, albeit reasoning on entirely different lines, using the best interest standard. The American court used an analogy quite similar to the Orthodox sages’ views -- which directly clashed with their Catholic cousins on the other side of the Oceanic Divide. The American court and the Rabbis focused on the primacy of preserving life, even if another life had to be jettisoned in the process.

Similar issues emerge in the IVF dilemma - on a societal level. Because creating extra embryos is required so that at least one embryo can have a life, the reasoning is applicable. Without creating the extra embryos, a necessary component of the IVF procedure, there would be little possibility of any IVF births. By ruling that destroying unused (or unhealthy) embryos is unacceptable, the entire procedure is in peril, depriving unfertile parents of the possibility of having genetically related children.

These cases graphically illustrate that while various legal routes of analysis yielded the same result, the religious approaches produced different outcomes. We should be ever mindful.

How do we chart a brave new legal or moral course given the monstrous divide in religious and political views and the monumental advances in medicine?

Consider: If Koop’s dilemma were brought before the Alabama courts today, even after the remedial legislation, he would be indicted for murder.

[1] This argument has been raised in the abortion context as well. “Religious Abortions” The Economist

[2] Central Manchester Healthcare Trust vs. Mr. and Mrs. A, decided in 2001. The American case occurred in 1997.

[3] Here is ChatGPT’s simplified explanation: “The principle of double effect addresses actions with both good and bad outcomes. Suppose the intention behind an action is good, even if it leads to foreseeable harm. In that case, the action may still be considered morally acceptable if the harm is a byproduct of the good action, not an objective. The good outcome should also outweigh the harm, and there should be no other way to achieve the good without causing harm. The principle is debated due to challenges in assessing intentions and potential misuse. Nevertheless, it provides a framework for evaluating complex moral situations, emphasizing the importance of intention and proportionality in decision-making.”