COVID, the "stomach flu", RSV, influenza, measles, and the common cold all have two things in common: 1) They are all highly contagious; 2) They are all caused by viruses and will make you miserable. While we wash our hands with antibacterial soap in the hope that we can dodge nasty bacteria, the more common threat to our health is viruses – nature's perfect machine.

Are viruses alive?

There are two schools of thought here: 1) Viruses are not living, and 2) That's wrong. Viruses do not come close to meeting the generally accepted requirements for defining what it means to be "alive".

For example, they:

- Don't take in nutrition or excrete waste

- Don't respire

- Don't move on their own

- Don't make or use energy on their own

- Don't have cells

- Neither grow nor shrink

- Have no nucleus

Perhaps, the best description for viruses is "a complex bag of chemicals."

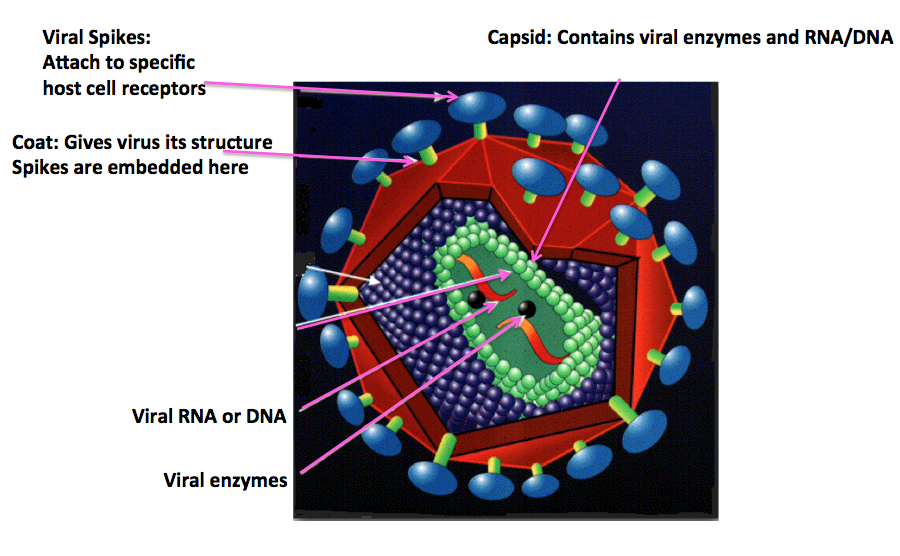

But viruses have a significant impact on living organisms as they are evolutionary miracles — microbes that exist solely to reproduce. They do so with perfect efficiency and no waste. Each virus contains the absolute minimum amount of "stuff" required to perform all its functions: genetic material, enzymes, and proteins that keep it intact until it reaches and enters the intended host cell. Then, the virus tricks the cell into doing all the work. Before we go into how it works, below is a cartoon that represents a typical virus. Note that there isn't much there, especially when compared to any living organism. But a virus is remarkably efficient with what it has.

Viral structure. Image: Stanford University

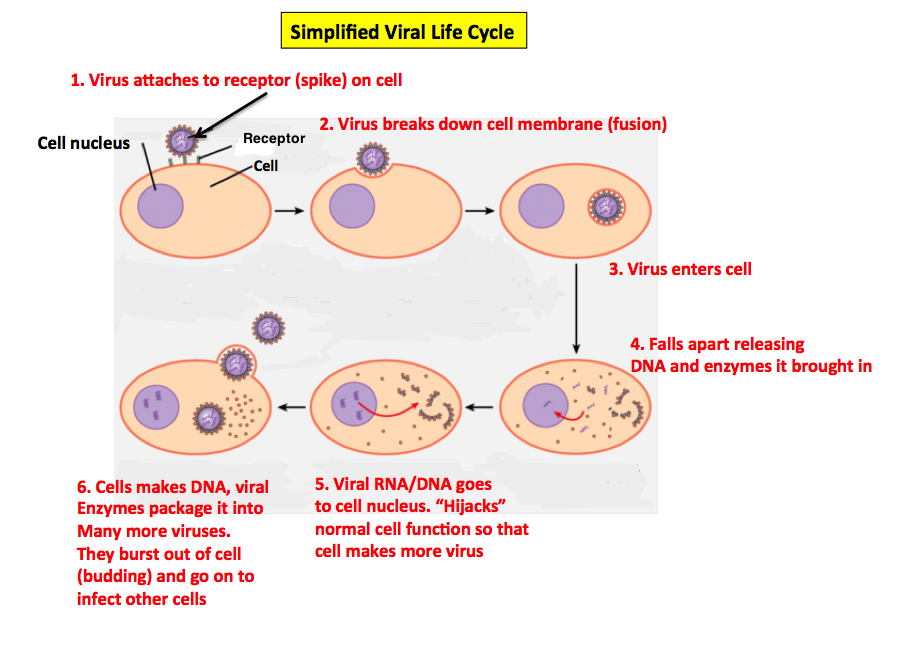

The actions of this "bag of chemicals," which is about 100 times smaller than a bacterium, are nothing short of amazing. It is much "smarter" than the cell that it infects. Using specifically-shaped protein spikes to locate and attach itself to the host cell, along with its genetic material and a few enzymes, each with a specific function, the virus turns the cell into a virus factory. It lets the cell do all the work. The virus does nothing, except reproduce, courtesy of the cell, which provides the energy and the mechanisms necessary for viral replication. This is why viruses are referred to as obligate parasites. They do not function in the absence of a host cell. The following cartoon is a simplified representation of a viral life cycle. What the infected cell gets out of this isn't clear, but the virus gets a lot.

(Modified from opentextbc.ca)

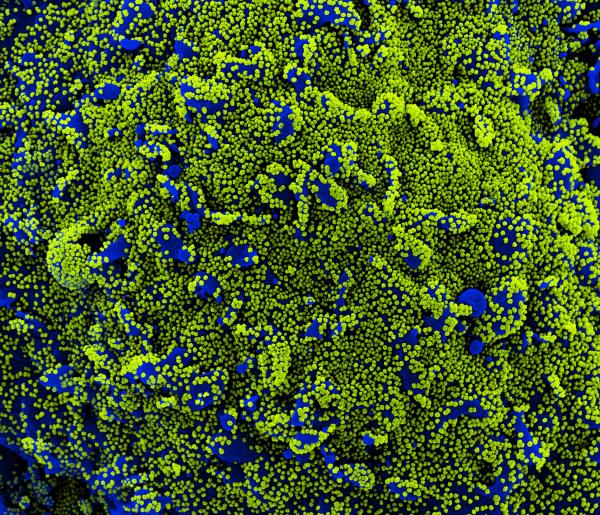

There's no waste, no energy required — simply the perfect reproductive machine that isn't even alive. Viruses are absolute wonders of nature. This is what they look like. The following shot is an electron microscopy image of a human white blood cell that's at the "budding" stage, where the multiple HIV particles (purple) that it just produced are breaking away from the host cell (blue). Note the difference in size between the cell and the viruses.

Image: Immunopedia

Ain't life funny? While we sit around watching cats on TikTok and doing crossword puzzles, we may think about how high-tech and sophisticated we are. Meanwhile, trillions of these perfect little monsters effortlessly float around in our blood, patiently waiting to find the proper home. At this point, they will go in and try to kill us. That's the life, right?

#This is an updated version of an article that appeared in 2016.