It's pretty well known that getting a good night's rest on a regular basis is very important for your health. It helps in the fight against weight gain and one's health suffers without adequate sleep. Now we're learning that overnight disruptions may have detrimental effects on cognitive health.

A new meta-analysis published in the journal Sleep Medicine found that middle-aged adults who suffered from insomnia, nightmares and regular bouts of broken sleep were more likely to face cognitive impairment in their later years.

The counterpoint to these findings, however, is that they were derived from self-reported data from four Scandinavian studies, so the data was not subjected to objective measurement by researchers. But given the large number of participants – two of the studies followed more than 3,300 subjects for over 20 years – the results carry some insight.

The authors of the study, "Sleep disturbances and later cognitive status: A multi-centre study," from the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, and Imperial College London, used a test called the Mini Mental State Exam. They wrote that the MMSE "is a commonly used instrument to measure cognitive status and screen for dementia," which includes "30 items covering the cognitive domains of registration, orientation, recall, attention, calculation, naming, repetition, comprehension, writing and construction."

Lower MMSE scores were a product of nightmares and regular episodes of interrupted sleep.

Lower MMSE scores were a product of nightmares and regular episodes of interrupted sleep.

The results showed that "sleep disturbances, including maintenance/terminal insomnia, in late life were associated with poorer cognitive status after 3-11 years," the authors wrote. Meanwhile, "nightmares in midlife were associated with poorer cognition in late life with a follow-up of 21 and 31 years. Moreover, midlife insomnia was associated with worse cognitive status measured after 21 and 31 years."

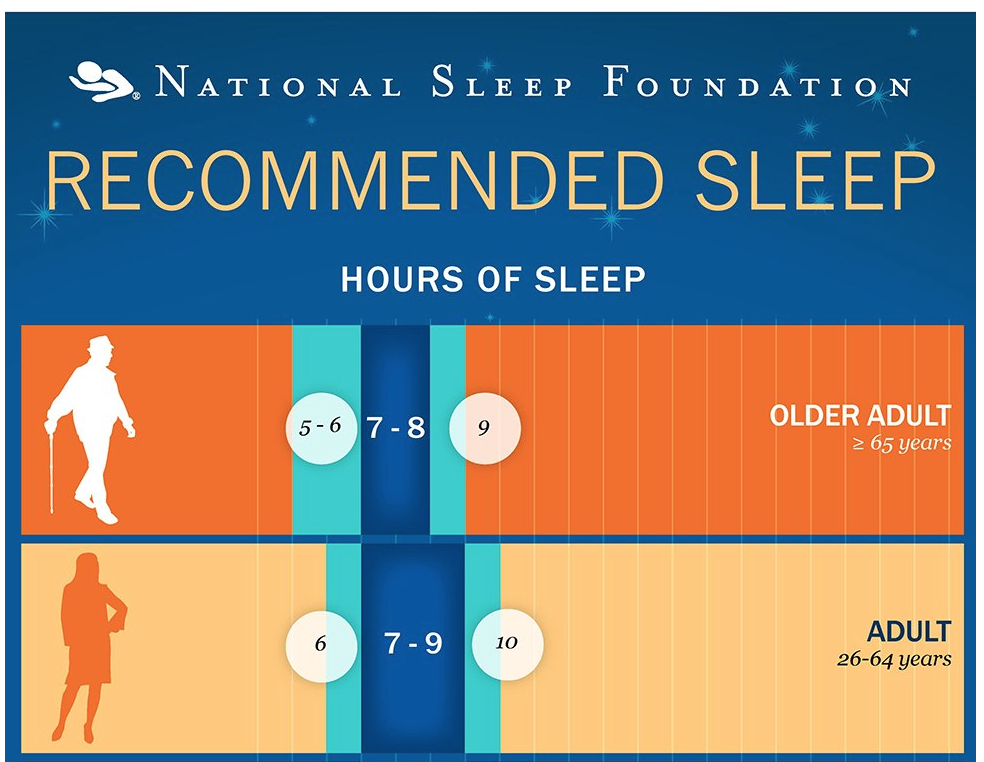

Adults between the ages of 26 and 64 should get 7-to-9 hours of sleep each night, according to recommendations by the National Sleep Foundation, while those 65 and older should get 7-to-8 hours each night.

The authors note that the results were "attenuated" when adjusting for lifestyle factors, that include cardiovascular health, consumption of alcohol, and smoking. But, they added, they should be weighed against the study's many strengths, such as the "large sample sizes from several population-based studies from two different countries" – Sweden and Finland – "long follow-up durations, assessment of different sleep parameters (including different types of insomnia), samples of men and women, and adjustments for several potential confounders."