Grace Murray Hopper was born in New York City in 1906 and attended Vassar College before receiving her PhD in mathematical physics from Yale University in 1934, returning there to teach on graduating from Yale. Her educational quest didn’t seem particularly onerous – climbing the ranks of the Navy hierarchy proved far more difficult. Rather than sex discrimination, Grace’s obstacles were due to age discrimination.

First, she was rejected because she was too old, age 34, and then because her diminutive physical frame didn’t meet physical criteria. (She had to get an exemption because, at 105 pounds, she was 15 pounds beneath Naval standards). Not accepted by the regular Navy, she joined the reserves. Four years later, now 38, she requested a transfer to the regular Navy. Again, she was rejected because of her age. So, Dr. Hopper stayed in the reserves, where she remained until retiring in 1966. However, in 1967, she was recalled, this time to active duty, where, save for two short retirements from which she was quickly recalled, she remained until permanently retiring at age 79, a year after earning her admiral’s stripes. At the time of her retirement, she was the oldest active-duty commissioned officer in the US Navy.

A Brief History of Computers

Faster than any existing computational device, able to add 5,000 numbers in a single second, and more powerful than its major competitor, the Harvard Mack I, “the Great Brain,” Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer (ENIAC), debuted in 1946.

But, ENIAC had no internal storage and had to be programmed manually for each new operation. Five years later, J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly created the first American general-purpose electronic, the Universal Automatic Computer I (UNIVAC I), produced by their company, Eckert–Mauchly Computer Corporation (EMCC). It was here, at the Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation, that Grace Hopper started laying tracks.

“The Queen of Code.” Or “The Mother of Cobol”

At its inception, early computers were thought to be sophisticated calculators – a slide rule-on-steroids. Each instruction was written in a symbolic code, which had to be laboriously recopied each time an operation was done, a sure invitation to mistakes. It was Grace Hopper who created the solution to avoid the time-consuming, error-prone recopying business,

“So I built the first compiler. It was a mathematical compiler. It translated mathematical notation into machine code.”

With Grace’s invention, once an instruction was written, it needn’t be re-written. But machine code used symbols instead of words, reflecting the way mathematicians (but not the rest of us) think, something Dr. Hopper was well aware of, writing:

"Very few people are really symbol manipulators. If they are they become professional mathematicians, not data processors. It's much easier for most people to write an English statement than it is to use symbols … So I decided data processors ought to be able to write their programs in English, and the computers would translate them into machine code.”

But she was rebuffed, as conventional thought was that “computers could only do arithmetic,” as no one thought such an invention was feasible.

This didn’t stop her, and by 1952, she had developed a compiler, a program that “translates” English terms into machine code understood by computers. The program initially called FLOW-MATIC was instrumental in Hopper’s development of COBOL, the Common Business-Oriented Language, a high-level programming language still used today.

The ability of the compiler to translate symbolic language into verbal-speak was critical in extending computer use to the business sector. As Dr. Hopper remarked:

“[When] I … was charged with the job of making it easy for businessmen to use our computers,…I found it was not a question of whether they could learn mathematics or not, but whether they would. … They said, 'Throw those symbols out — I do not know what they mean, I have not time to learn symbols.'”

So she did. Her new compiler could instruct the computer to “subtract income tax from pay” instead of trying to write those instructions using all kinds of symbols.

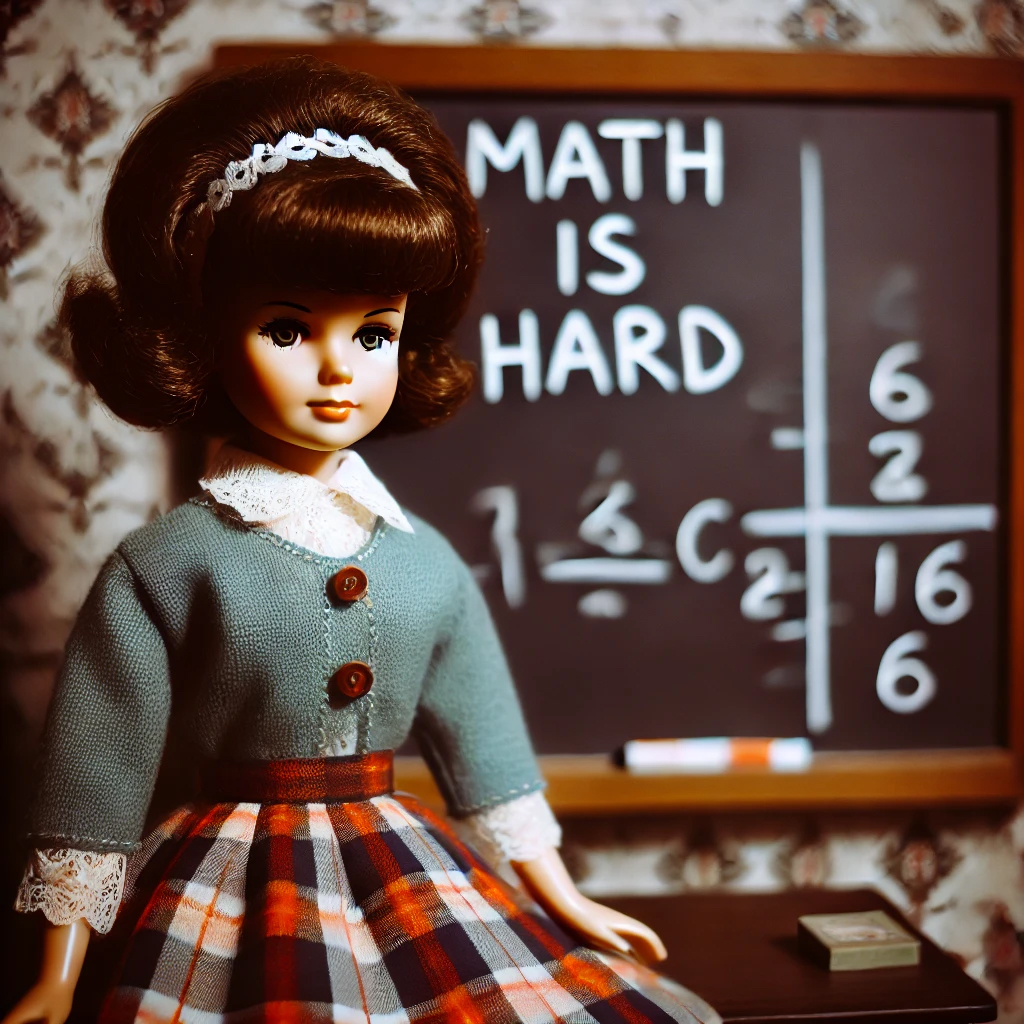

“Math is Hard,” Sayeth the Barbie. No, It’s Not, Sayeth Grace

If Grace Murray Hopper were to identify her most important gift, it would be curiosity, a trait that author Walter Isaacson noted also bespoke the mind of Leonardo da Vinci.

Grace said, “I always claim that I had a strong resemblance to the elephant’s child in Kipling’s Just So Stories who pokes his nose into everybody’s business.”

She was blessed with parents who encouraged her mathematical inclinations. Those of us who played with Barbie in 1992 might remember Barbie saying, “Math is hard.” Not so for Grace, whose father encouraged her mathematical abilities, with Grace noting that mathematical inclination isn’t unusual in women, “it’s just that we get dissuaded.”

She was blessed with parents who encouraged her mathematical inclinations. Those of us who played with Barbie in 1992 might remember Barbie saying, “Math is hard.” Not so for Grace, whose father encouraged her mathematical abilities, with Grace noting that mathematical inclination isn’t unusual in women, “it’s just that we get dissuaded.”

“They hit a hard problem, and somebody’s apt to say, “Oh, girls can’t understand that.” They’re not encouraged by teachers or parents. That didn’t happen to me.”

Girls seem to be particularly adept at coding, as exemplified by the Hollywood icon, Hedy LaMarr, who demonstrated that manipulating radio frequencies at irregular intervals between transmission and reception formed an unbreakable code that could prevent secret messages from being intercepted (an invention for which she received a patent in 1942). This has led to the "spread spectrum" technology that is the basis of modern wireless communication technology, enabling Wi-Fi connections.

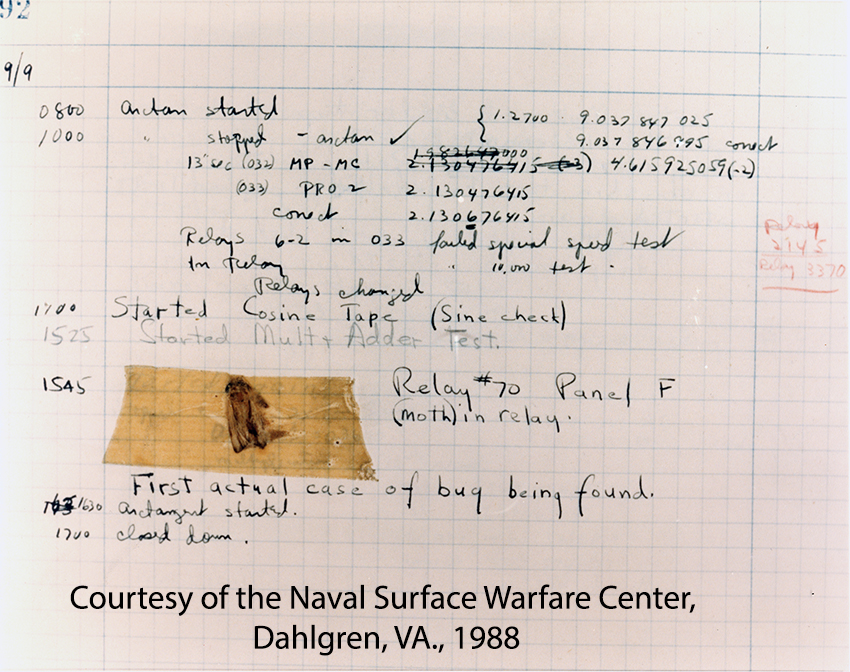

The First Computer Bug

Dr. Hopper’s wit and wisdom are legendary, known for coining the term debugging, for correcting computer code that doesn’t work or misbehaves. Computer lore recounts that a main frame she was using failed to work, and the first computer bug was a moth that “infected” the computer’s mainframe, stuck in a relay, and impeded the computer's operation. The “bug” was retrieved, appended to the day’s log notes, and preserved. She also popularized the term “nanosecond.” To  demonstrate a nanosecond, one billionth of a second or the time it took light in a vacuum to travel 30 cm (11.8 inches), she handed out wire pieces of that length. She contrasted that one-foot wire with the distance light traveled in a microsecond, a millionth of a second - 300 meters or 984 feet. Finally, she characterized an individual grain of ground pepper as the distance light traveled in a picosecond, a trillionth of a second.

demonstrate a nanosecond, one billionth of a second or the time it took light in a vacuum to travel 30 cm (11.8 inches), she handed out wire pieces of that length. She contrasted that one-foot wire with the distance light traveled in a microsecond, a millionth of a second - 300 meters or 984 feet. Finally, she characterized an individual grain of ground pepper as the distance light traveled in a picosecond, a trillionth of a second.

Leadership and Innovation Even if You Don’t Go Near the Water

If those of us who are scientifically inclined value Dr. Hopper’s contribution to STEM, those in the leadership field similarly extol her virtues. She was one of ten leaders selected by Admiral James Stavridis for his book Sailing True North: Ten Admirals and the Voyage of Character. The chapter devoted to Grace Hopper, entitled “Don’t Go Near the Water,” is particularly noteworthy. Since she never went to sea or led carrier battle groups into combat, her inclusion in a book populated by military geniuses acclaims her innovation and reputation as a pioneering thinker. Calling her “Rear Admiral ‘Amazing Grace’ Brewster Murray Hopper,” Admiral Stavrides’ admiration is palpable, noting her blended attributes of self-confidence and humility, which he termed magnetic, Adm. Stavrides all but credits her as single-handedly pulling the stodgy and technically out-dated Navy into the future, by sheer conviction and intrepid daring-do.

Perhaps the heart of Grace Hopper’s inspirational wisdom can be best gleaned from her aphorisms:

“The contemporary malaise is the unwillingness to take chances. Everyone is playing it safe. We’ve lost our guts ... But we built this country on taking chances.”

"Humans are allergic to change. They love to say, 'We've always done it this way.' I try to fight that. That's why I have a clock on my wall that runs counter-clockwise ... That’s so nobody … can ever say we’ve always done it this way. It tells perfectly good time. It just shows there was never any good reason why clocks had to go clockwise.”

On information and knowledge: "We're flooding people with information. We need to feed it through a processor. A human must turn information into intelligence or knowledge.”

Recognizing her ability to inspire today’s young women, even after her demise, the Anita Borg Institute holds the largest conference for women in technology called the Grace Hopper Celebration each year.

An officer and an inspiring visionary might be a wonderful epitaph.