Sometimes a remedy to a catastrophic health emergency is so simple, so straightforward, that it's truly mind-boggling when that precaution is not being implemented. And when that precaution carries life-or-death consequences while being virtually cost-free, we must ask ourselves, "How in the world is this not happening?"

Unfortunately, that's a question that continues to plague grief-stricken parents – year after year after year – who have learned that their teenager has died from heat stroke suffered on the playing field.

After struggling with the unthinkable – that they will never see their child again – only then do these parents learn a truly heartbreaking fact: that their teenager could have been saved if only a large tub of ice water was on hand.

It can't be that simple, right? Just icy water, and all these senseless fatalities could have been avoided?

Yes, it's just that simple. But by and large high schools and colleges, and the organizations that govern them, haven't mandated that cooling tubs be readily available for athletes whose body temperatures climb dangerously high, most often in the summer months.

And it's just that simple because all the medical research shows that when signs of heat exhaustion and heat stroke appear, there is a 100 percent survival rate when someone with a 104-degree core body temperature is immersed in cold water within 5 to 10 minutes of diagnosis, according to the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Last week, the parents of William Shogran, Jr., a Florida football player who succumbed to heat stroke in Aug. 2014, now that their litigation against the school district was finalized and they can speak openly, have begun publicly lobbying the Florida High School Athletic Association to have ice baths on hand for athletes. Their 14-year-old's core temperature soared to 107 degrees, with no method on hand to lower it during that fateful summer football practice. There was also no athletic trainer on site.

Another Florida teenage football player died under similar circumstances last year. Zach Martin-Polsenberg, 16, passed away on July 10, 11 days after his temperature reached 105.4 degrees, measured only when emergency medical technicians treated him. No cooling tub was available as well. Zach's parents are joining with the Shograns to get Florida high schools to mandate the availability of ice baths and thermometers at athletic practices and games.

Knowing how easily avoidable these fatalities are, safety advocates have become even more outspoken about the foot-dragging and ignorance on display by many high school officials.

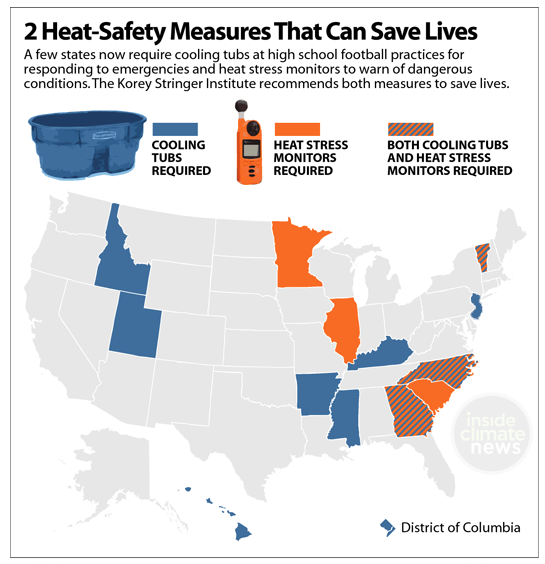

"It’s really a failure of responsibility,” said Douglas Casa, Ph.D., who leads the Korey Stringer Institute, a leading organization on heat stroke and its link to player fatalities, as reported in June by the Fort Myers News Press.

“How many deaths do we still have to have? The most ludicrous thing in the world is that a school can support the cost of all the things to have an athletic program," continued Casa. "But we’re not going to make the suggestion that they should have an immersion tub if a person should happen to have heat stroke in Florida in August playing in football gear?”

“How many deaths do we still have to have? The most ludicrous thing in the world is that a school can support the cost of all the things to have an athletic program," continued Casa. "But we’re not going to make the suggestion that they should have an immersion tub if a person should happen to have heat stroke in Florida in August playing in football gear?”

Stringer, a former NFL veteran who played for the Minnesota Vikings, died of exertional heat stroke in 2001 during training camp. His wife, Kelci, established the Institute with Dr. Casa at the University of Connecticut.

KSI reports, citing NCCSIR data, that since 1995 "three football players a year on average have died of heat stroke, most of them high schoolers." And just three weeks ago the University of Maryland, led by its president Wallace Loh, publicly apologized to the family of Jordan McNair, a 19-year-old football player who died in June, 15 days after the school failed to diagnose and treat him during a searingly-hot practice.

The school's athletic director, Damon Evans, said while trainers were on hand they never took McNair's temperature and did not immerse him in an ice bath. When emergency services reached him his core temperature was 106, and they were able to lower it to a safe 102 degrees within 90 minutes, but nowhere soon enough to get McNair out of life-threatening danger. Experts agree a quick response and ice bath immersion would most certainly have saved his life.

Here's what heat illness looks like, according to NCCSIR, in its Annual Survey of Football Injury Research, published in February.

"Some trouble signs are nausea, incoherence, fatigue, weakness, vomiting, cramps, weak rapid pulse, flushed appearance, visual disturbances, and unsteadiness. Exertional heat stroke victims, contrary to popular belief, may sweat profusely as athletes are exercising."

There are those who will try to make the case that three deaths a year should not be a concern, that it hardly represents a crisis and we shouldn't make this such a big deal about this issue. But given that such an easy solution is at hand and one that's extremely effective at saving lives, is there any logical reason that we're not implementing this safeguard immediately – and everywhere this danger has even a chance of taking place?

Of course not. All it takes is a large plastic tub and ice.

Just add water.