George Bernard Shaw released his play, Pygmalion, in 1913, although the American public would recognize it in its morphed form, My Fair Lady. Among the many stories within the play is the detrimental effect of one’s speech on their chance for advancement in English society, what we call today's economic mobility. An article in PNAS updates us, turns out that little may have changed.

America has social classes, perhaps not as distinct as those of 19th century England or 20th century India, but classes nonetheless. Speech patterns reflect many components of socialization; our home lives, neighborhood, education, in short, they provide social cues as to our “class.” Someone listening to us can often infer our social status by comparing our utterances to their self-proclaimed ideal. “You only have one chance to make a first impression,” is the type of heuristic that captures the truth that those cues are out there. Speech is just one source for inference, but it may be more powerful; after all, you can wear a new suit, and you can choose your words carefully, but it is hard, but not impossible, to cover up a “Valley Girl” accent.

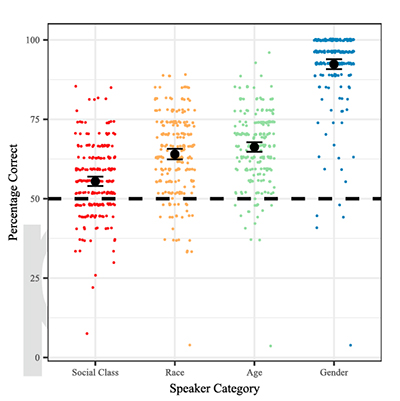

The researchers made use of audio records from the International Dialects of English Archive, a nonprofit collecting North American dialects. They played words as well as an extended speech from these recordings to the study participants in a variety of small studies. Based only on seven words, taken out of context, the participants had a better than chance ability to identify a speaker's social class, race, age, or gender. [1] And before you say or notice, that effect size concerning social class is small - only about 5% better than chance alone, but stay with me.

The researchers made use of audio records from the International Dialects of English Archive, a nonprofit collecting North American dialects. They played words as well as an extended speech from these recordings to the study participants in a variety of small studies. Based only on seven words, taken out of context, the participants had a better than chance ability to identify a speaker's social class, race, age, or gender. [1] And before you say or notice, that effect size concerning social class is small - only about 5% better than chance alone, but stay with me.

Using a standard of speech derived from Google's and Amazon's website, the researchers demonstrated that even for those same 7, out of context words, higher-social-class speakers deviated less from that standard. Study participants asked to rank these voice samples, based upon their sense of standard speech, were again able to separate between low and high social position. When provided with a longer speech sample in which individuals described themselves, the subjects again make distinctions between low and high social status. Interestingly, reading a transcript rather than hearing the speech was associated with a lower discriminatory ability – you could hide class by word choice more effectively than with actual utterances.

Here is the payoff study

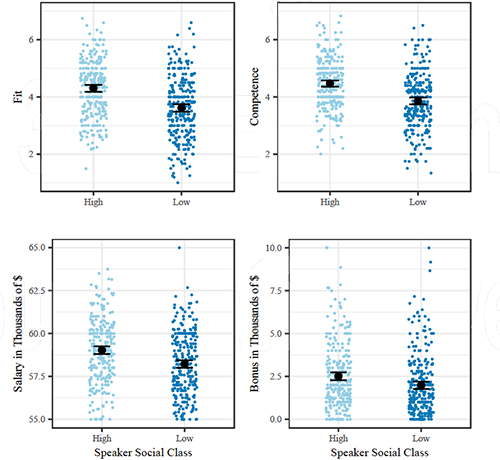

Twenty prospective job applicants were recruited from a larger cohort to provide a wide range of social statuses and recordings made of them answering, “How would you describe yourself?” It was done before the actual job interview for a position as a laboratory manager, and to the best of their ability, the researchers attempted to make it seem like small talk bantering. Two hundred and seventy-four study subjects, all with hiring experience, were asked to determine from the recordings or written transcripts the candidates’ fitness for the job, competence, recommended starting salary, sign-on bonus, and of course, their social status. Without a resume or any other information, to guide them, the "hirers" were able to discriminate between social classes from hearing the candidates or reading the transcript; again, speech provided more significant discrimination than the transcript.

When the researchers looked at those other impressions of the job candidates, they found that higher social class based on less than a minute's worth of speech implied greater competence and fitness for the job, which in turn translated into a higher base salary offering and sign-on bonus.

When the researchers looked at those other impressions of the job candidates, they found that higher social class based on less than a minute's worth of speech implied greater competence and fitness for the job, which in turn translated into a higher base salary offering and sign-on bonus.

"…although these perceptions of social class only elicited minimal accuracy relative to random chance, it was enough … to produce a reproduction of economic inequality through biased hiring practices that unfairly advantage higher-social-class people to the detriment of their relatively economically disadvantaged counterparts.”

It is hard to tease out this type of unconscious bias in hiring decisions so let us not jump to any conclusions. But the study does show how first impressions can cascade to influence our decision making. For the moment, kudos to GB Shaw for pointing out the problem so long ago. In the meantime, let us practice together, “The rain in Spain stays mainly in the plain, " or for that past this stage, "In Hertford, Hereford, and Hampshire, hurricanes hardly ever happen." [2]

[1] For this part of the study, social class was identified with high school or higher education and age separated as above or below age 35.

[2] The song is from My Fair Lady and is the pivotal point when Eliza loses her Cockney accent and speaks “all proper.”

Source: Evidence for the reproduction of social class in brief speech PNAS DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1900500116