“Between 2002 and 2013 statin use in the US nearly doubled, cholesterol levels are falling, yet cardiovascular deaths appear to be on the rise.”

Reducing and preventing cardiovascular disease is much more than a cottage industry, spawning a range of treatments and in the last several years, guidelines, to protect those at risk – guidelines with ever lower acceptable cholesterol levels requiring increase dosages, and a variety of drugs with different mechanisms of action, frequently at a higher cost. A new meta-analysis stops the treadmill of care long enough to ask how well the battle is going.

The researchers identified randomized control trials that used the 2018 American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology guidelines and one of the three classes of medications used to reduce cholesterol. They further restricted their search to control groups receiving placebo or “usual” care for over a year, as well as studies that would allow calculation of an individual’s 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event. [1] They identified 35 studies, the majority of which were of excellent quality, a few were marked down for small populations, not using a placebo in the control arm or other concerns over a biased population.

A quick word on the limitations. The researcher’s criteria excluded some critical clinical trials that consider patients that were over 75 or where data did not allow for complete analysis. And these trials were not intended to assess clinical outcomes, simply to look at the effect of these medications on cholesterol. Apply salt as necessary.

Results

- Of 13 RCTs that met the guidelines for LDL (bad cholesterol) guidance, one reported a mortality benefit, five reported reduction in cardiovascular events (heart attacks or strokes). In the 22 studies not meeting the current guidelines, four reported a mortality benefit, 14 a reduction in events. The lack of consistency with the intended effect of the guidelines, lowering mortality and morbidity, was true for all three classes of medications.

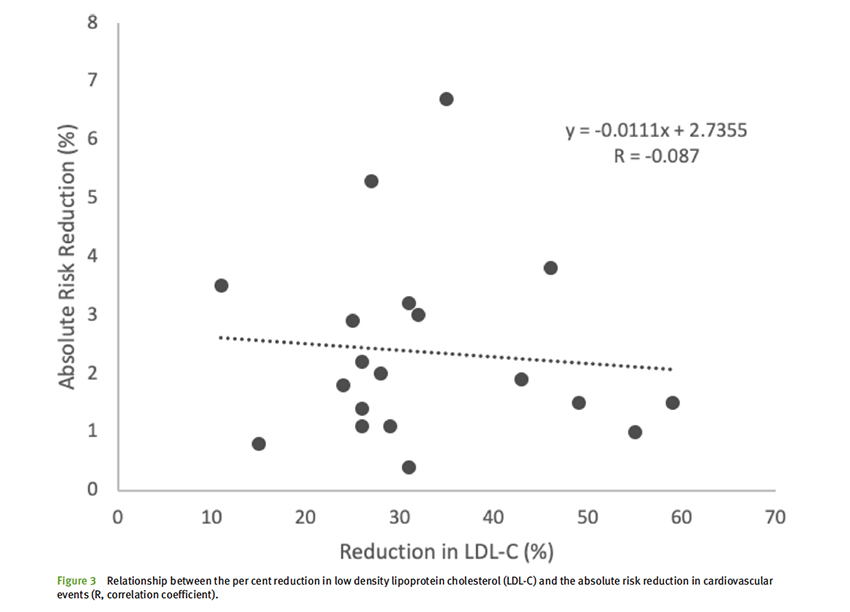

- Beneficial reductions in cardiovascular events were seen with lowering LDL by as little as 11%-15%, and no benefit was seen in studies lowering LDL by 50% or more. That discordance in cholesterol reduction and benefit held when the number needed to treat, NNT, was calculated [2] In one study, an LDL reduction of 35% resulted in an NNT of 30, in another study where LDL was further reduced to a total of 55%, the NNT climbed to 250.

“In most fields of science the existence of contradictory evidence usually leads to a paradigm shift or modification of the theory in question, but in this case the contradictory evidence has been largely ignored simply because it doesn’t fit the prevailing paradigm.”

What’s up with the guidelines?

First, there is no ill intent here. There is no Big Pharma or Big Medicine plot. The AHA/ACC guidelines are clear are emphasizing first changes in life-style, taking better care of yourself through how and what you eat and how much you exercise and sleep. But we all know that those changes in habits are far harder to achieve than merely taking a pill, even when the discussion is individualized and informed as to risk and benefits.

Risk scores used in stratification are flawed. In one study, patients who had cardiovascular events were retrospectively risk-stratified and were found not to need cholesterol-lowering medications. In another, 44% of candidates for statin therapy had coronary artery calcium [3] scores of zero, suggesting low or no risk.

Our understanding of the role of LDL’s is flawed. Despite overwhelming evidence than an elevated LDL contributes to CVD, lowering LDL has shown no consistent benefit. There are other factors at play and a continued emphasis on improving outcomes by lowering LDL further and further seems short-sighted. There is no linear relationship between LDL reduction and outcome. Some would argue that there is no correlation at all, as the graph depicts.

At a minimum, we should expend more effort in improving our risk stratification, too many patients are being improperly managed, and often at great expense to society and the individuals. More importantly, we need to consider how the hierarchy of modern science, constructed by academia, corporate interests, and government funding in equal measure, makes it difficult for new ideas and approaches to bubble up. “Follow the money” applies as much to our choice of research topics, research funding, and commercialization as it did to tracking more nefarious political actions.

At a minimum, we should expend more effort in improving our risk stratification, too many patients are being improperly managed, and often at great expense to society and the individuals. More importantly, we need to consider how the hierarchy of modern science, constructed by academia, corporate interests, and government funding in equal measure, makes it difficult for new ideas and approaches to bubble up. “Follow the money” applies as much to our choice of research topics, research funding, and commercialization as it did to tracking more nefarious political actions.

[1] A 10-year risk calculation has been a way to narrow down risk categorization

[2] NNT or numbers needed to treat tells you how many patients need to be treated to improve the outcome for one patient. An NNT of 250 means 249 patients take and pay for medication with no benefit while providing a benefit to the remaining patient.

[3] Frequently, atherosclerotic plaques, responsible for cardiovascular events, contain calcium, which can be quantified on imaging. Coronary artery calcium scores are an alternative means of assessing coronary risk.

Source: Hit or miss: the new cholesterol targets BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine DOI:10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111413