This is an easy document to poke fun. It is full of cultural new-speak that can be jarring when heard, let alone considered. The whitepaper provides guidelines for healthcare’s more formal speech in journal articles, presentations, and policy. As a physician and writer, language holds a special role for me. I agree with the authors,

“… that language evolves over time, and words come in and out of favor. Context also matters, and words that might be appropriate in some circumstances may not be appropriate in others. … the meanings of words and their usage change over time.”

They begin with narratives – the stories we tell, to explain ourselves to the world and, in turn, the world to us. Despite electronic health records’ attempt to stifle and regulate our patients’ narratives of their illness into checkboxes and dropdown menus, narrative is alive and well, in the exchanges between physicians and nurses as they handoff care two or three times daily in our hospitals.

In the public discourse of social media, much of the time, what one polarized side or the other contends is fake news or science has far more to do with the narratives than the underlying facts. As I have written, most of our disagreement lies in how the dots are arranged, not the dots themselves.

“Narrative shape our thinking and assessment of the world around us. They determine who we “see” and whose needs are and aren’t prioritized. Importantly, dominant narratives shape our understanding of what we deem possible and not possible.”

The authors consider the language we use to describe an individual, suggesting we use more person-centric wording – a patient with diabetes, not a diabetic. I get that diabetes is one of their characteristics, not their totality. But person-centric seems to be artifice when we replace “homeless patient” with “a patient experiencing homelessness.” Using “with” or “experiencing” seems to the authors to be less dehumanizing; I miss the distinction. They also call out the use of words with violent connotations; we should not tackle or target a high-risk population; we should “Engage/prioritize/collaborate with/serve groups with higher risk.” [emphasis added] [1]

Spoiler alert – now is when we begin to touch upon divisive words and thoughts

“But what if we shift the narrative from an individualistic lens to an equity lens? … People are not vulnerable; they are made vulnerable.”

That may well be true, but for the physician caring for the patient, who is “economically marginalized,” that concern provides context but may be too great an enlargement of the scope of their work.

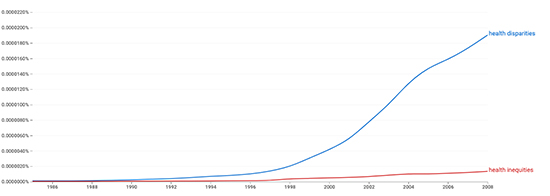

Their example of the “equity” lens is the use of the term health disparities – describing differences in care or outcome in an emotionally neutral, quantitative way. They suggest instead, health inequities

“health differences that are unjust, avoidable, unnecessary, and unfair—no longer a simple calculus of difference, but an assessment based on a value judgment.”

As the Google Ngram, which measures word frequency, demonstrates, health inequities are yet to catch on. Why inject value judgments; doesn’t that allow for advocacy and promote analytic bias? More importantly, whose values are to be injected, physician or patient?

As the Google Ngram, which measures word frequency, demonstrates, health inequities are yet to catch on. Why inject value judgments; doesn’t that allow for advocacy and promote analytic bias? More importantly, whose values are to be injected, physician or patient?

Anti-vaxxers

The issue of differing physician and patient values, being sensitive and aware of cultural differences to provide more helpful, dare I say sensitive care, has been a touchstone since I was a medical student long ago. Physicians treat people of many cultures, so a portion of our medical education involved learning or developing “cultural competence.” Today, that term carries some unwanted baggage. Cultural competence is felt to be

- Too reductive, reducing a culture to a few concepts, often along the easily drawn lines of race, ethnicity, or social standing. I have been influenced by Isabel Wilkerson and think caste is a far more encompassing word for those distinctions.

- A quality that can be obtained and measured by a test or, worse still, by a “learner’s confidence and/or comfort.” Admittedly, even if we could objectively measure cultural competence, it does not measure the ability to connect with another individual - that resides in empathy.

The preferable term is “cultural safety,” which comes to us from the experience and interactions of medical professionals and the indigenous people of New Zealand [2]

“Cultural safety calls on medical professionals and health care institutions to create spaces for patients to receive care that is responsive to their social, political, linguistic, economic and spiritual realities. Culturally unsafe practices, in contrast, are actions that diminish, demean, or disempower the cultural identity and well-being of patients.” [emphasis added]

Here is the question to ponder. Through our speech and actions, are we, as a profession, providing a culturally safe space for those described by others as anti-vaxxers? (A more person-centric, health inequity term might be persons struggling with experiences making them unlikely to be vaccinated)

As a physician, I believe vaccination is a public health good; and that the individual anti-vaxxer is misinformed or has very different beliefs regarding their responsibilities as citizens. Only when we aggregate the “persons struggling with experiences making them unlikely to be vaccinated” is it that anti-vaxxers take on a political tone – either warrior or sheep. I am certainly not using a value-free term. Am I phrasing in terms of health inequity conflating the belief with the person?

Some would argue that it is not a health inequity because, as the definition is given, it must be an “avoidable, unnecessary” factor creating the inequalities. But to practice cultural safety, my narrative must be responsive to their social, political, and spiritual realities, to their meaning of avoidable and unnecessary.

At what point in our attempt to repeatedly educate do I cross the line and make them culturally unsafe? Do the anti-vaxxers deserve the scorn they receive? Do you feel the same animus towards people with obesity or with a habit of smoking brought about and maintained by corporate interests? Are anti-vaxxer and “inner-city” both political dog whistles?

[1] I’ve written before how those word choices seem to have reflected our view of the immune response – antibodies attack, our immune system is mobilized. But, in that instance, the words often echoed the scientists' underlying experience of life as much of the early work began in the aftermath of World War I and II.

[2] Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. Int J Equity Health DOI: 10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3

Source: Advancing Health Equity: A Guide to Language, Narrative and Concepts