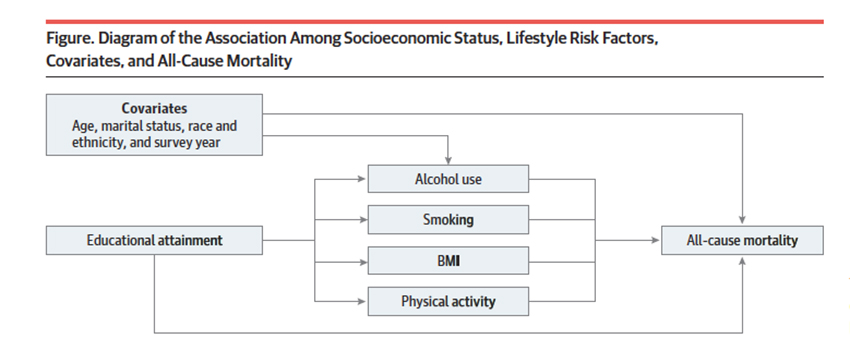

Most health outcomes studies have a laundry list of covariates, e.g., age, gender, co-morbidities, and socioeconomic factors, all statistically adjusted to provide outcomes. But are all those co-variants equal? Is age more or less important than, say, educational level? Mediation analysis, a statistical means of assigning a weight or percentage to a covariate’s impact upon an outcome, tries to turn that laundry list into a hierarchy of concerns. Perhaps this image from the paper will help.

What it tries to depict is how these covariates influence one another. Covariates directly influence mortality and indirectly, through their impact on those 4 “lifestyle” choices. Similarly, education has both a direct effect on mortality and an indirect one, again, through the fab four. The research goal was to break up the lifestyle risk factor monolith and assign values to how much, or little those lifestyle choices impacted all-cause mortality.

What it tries to depict is how these covariates influence one another. Covariates directly influence mortality and indirectly, through their impact on those 4 “lifestyle” choices. Similarly, education has both a direct effect on mortality and an indirect one, again, through the fab four. The research goal was to break up the lifestyle risk factor monolith and assign values to how much, or little those lifestyle choices impacted all-cause mortality.

The dataset comes from the National Health Interview Survey, a long-term cross-sectional survey of households by the CDC. The research utilized data from 1997 to 2014 for individuals aged 25 to 85. [1] All covariates were self-reported, the outcome of mortality from our national database. The groups were stratified by educational attainment into low, high school or less; medium, some college, and high, a college degree or more. The focus was on the mediating roles of alcohol use, smoking, BMI, and physical activity.

Slightly more than four hundred thousand participants, mean age of 49.4, 55% women, 17% Hispanic, 14% Black, 64% White, and the remaining 5% included Asian and Pacific Islanders and American Indian or Alaska Native. 45% reported low educational attainment, 28% medium, and 27% high attainment. They were followed for a mean of roughly 9 years.

Let’s start with the old news.

- At baseline, 58% drank very little, 55% had never smoked, 35% had a healthy weight, and 47% were physically active.

- Based on the roughly 50,000 deaths during the interval, those with the lowest educational attainment had the highest mortality, 187.4 deaths per 10,000 person-years. [2]

- Those with moderate education experienced 105.7 deaths per 10,000 person-years and those with the highest educational attainment 69.8 deaths/10,000 person-years.

- Low educational attainment was associated with more prevalent unhealthy lifestyles, e.g., smoking, drinking, physical inactivity, and an increased BMI.

And now, to the way those factors interacted with one another.

- For those with all the best lifestyle choices, low educational attainment alone resulted in 13.1 more deaths than those with high educational attainment.

- For men, low educational attainment resulted in 83.6 more deaths; 66% were attributable to lifestyle choices that increased exposure to harmful behavior. The contribution of smoking was 30%, physical inactivity 27%, drinking 16%, and BMI 6%

- For women, low education attainment increased deaths to a lesser degree, 54.8, but the influence of those unhealthy lifestyle choices was more significant, 80%. The contribution of smoking was 24%, physical activity 23%, drinking 11%, and BMI did not contribute.

- Men with low educational attainment were not more vulnerable to these choices than men with greater educational attainment; they chose unhealthy options more often.

- Women with low educational attainment appear to have increased physiologic vulnerability to alcohol use and physical inactivity

There is a great deal to unpack there, so let me offer a straightforward summary. Except for drinking and a lack of exercise for women with low educational attainment, lifestyle choices that increase exposure to unhealthy behavior drive disparities in outcome, not education. Smoking and physical inactivity are the biggest, badest choices. There are other socioeconomic factors to consider, and I am sure researchers will be reporting on them. But as the researchers write,

“Overall, these findings suggest that public health interventions that target smoking, physical inactivity, alcohol use, and the social, structural, and environmental contexts in which these behaviors develop among groups with low SES may yield important reductions in socioeconomic inequalities in mortality.”

[1] Researchers felt that participants less than age 25 had not necessarily reached their highest level of educational attainment and that those over 85 might not have complete information.

[2] Person years remain a difficult descriptor, at least for me, but it is the number of participants multiplied by the years of follow-up and is meant to standardize the results.

[3] For women, 7 drinks per week, 14 for men

Source: Educational Attainment and Lifestyle Risk Factors Associated With All-Cause Mortality in the US JAMA Health Forum DOI: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.0401