Heart failure (HF) [1] is a medical condition where the heart can no longer pump as effectively as it should and can result in swelling and shortness of breath. You may be aware of the condition because of all those Entresto ads. Now, swelling and shortness of breath may sound somewhat problematic, but when you speak to patients with HF, you will discover that it can be a very limiting debilitating disease. But patients with this condition will tell you, in the words of Rodney Dangerfield, “they get no respect,” especially when compared to patients with other bad diseases like cancer.

“Studies have shown that mortality due to HF is worse than certain types of cancer. …However, HF has not received a similar priority or profile such other serious health conditions such as cancer in terms of government policy or funding and thus cancer has seen a much greater improvement in survival.”

The study was designed to look at how often the term ‘heart failure’ was used in comparison to ‘cancer’ in web-based media and in parliamentary debates in the UK. It was a study funded by the Pumping Marvellous Foundation, a patient-driven foundation concerned about HF funded by patients and other stakeholders, a term that applies to pharmaceutical and medical device companies who provide treatments for these patients. This helps explain the concern about HF not getting the attention it deserves, but I do not believe it has resulted in biased findings – you can decide for yourself.

Heart failure accounts for more new cases than cancer or dementia and more deaths than dementia globally. Despite that:

- Heart failure was mentioned 14 times less frequently than ‘cancer’ in US publications.

- Heart failure was mentioned far less frequently than ‘dementia,’ except in the US press, where dementia was mentioned twice as often.

- These terms were used most frequently, as you would expect, in the medical literature. Still, despite there being just a 6% higher frequency of cancer-related deaths compared to those from heart failure, cancer was mentioned 8-fold more often.

- The disparity was even greater in the news, where cancer was mentioned 73 times more frequently, and in life and leisure media 71 times more often.

When heart failure was mentioned, it was usually in the obituary phrase, “X (has) died from/of heart failure” – in other terms, heart failure patient’s have no “agency” or control. Cancer was more often mentioned in conjunction with surviving or battling – these framings, as the researchers write, are “relatively active and empowered.” Even dementia’s mentioning offered agency and power to the patient, although most references were clinical, modifying dementia as senile or vascular, etc.

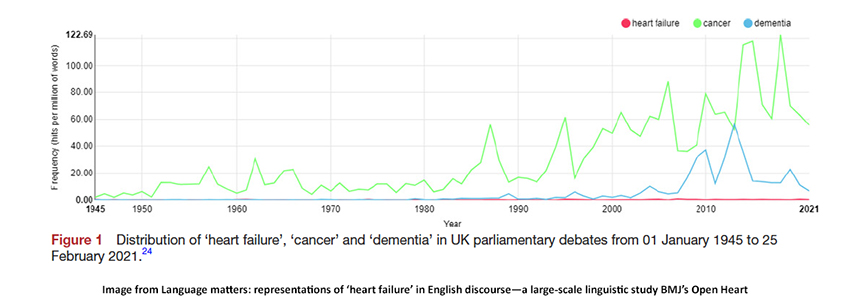

More importantly, the differences in mentions carried over to the UK’s Parliament – the source of research funds.

Cancer gets not all but a great deal of attention, heart failure some, but dementia seems to barely come to Parliament’s attention at all. Heart failure got fewer mentions than potholes, although the researchers quickly point out that it is unclear whether potholes are of more significant concern to the parliamentarians or their constituents.

“…figurative language through which people with cancer are framed as ‘survivors’ actively ‘battling’ their illness. Empowering framings of people engaged actively in opposition to HF do exist, but these are very much less typical than in discussions of cancer. There is little evidence of person-centred discussion about the experience, feelings and/or emotions of people with HF or their quality of life.”

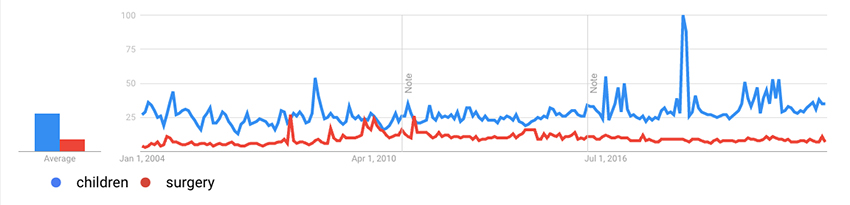

There it is, the real point. Heart failure has not been humanized in the ways cancer has, resulting in those patients who can be equally as ill and disabled not getting the respect and their disease not getting the funding they feel they deserve. The researchers believe that mentions are at least one metric of importance. Perhaps they are correct. I would only offer this counterfactual. Here is the search frequency, since 2004, for the terms children and surgery from Google Trends

Children as a search term is many fold more frequent than surgery. And politicians are constantly invoking “the children” in their pleas. Yet the median income of a pediatrician in New York City is $254,000; for a surgeon, $442,000.

That said, it is true that heart failure is under-discussed and framed in more clinical than human terms. Indeed, there is now a consideration to replace the term failure with dysfunction, hoping to better align word choice with patient self-image and expectations. I think that the word choice is not particularly clinically impactful, but as this other group of researchers believes, perhaps we should find out.

Source: Language matters: representations of ‘heart failure’ in English discourse—a large-scale linguistic study BMJ’s Open Heart DOI:10.1136/openhrt-2022-001988