Unlike many issues, such as climate change or how to deal with a pandemic, there is a near-universal scientific consensus that ballast water discharge can introduce non-native species that quickly become invasive, resulting in ecological damage, human health effects, and economic loss.

On October 22, 2022, 160 organizations wrote a letter to President Biden asking him to direct the EPA to finally establish discharge standards for ballast water from ships in compliance with the Clean Water Act. Thirty-four members of Congress asked for the same standards.

What is Ballast Water?

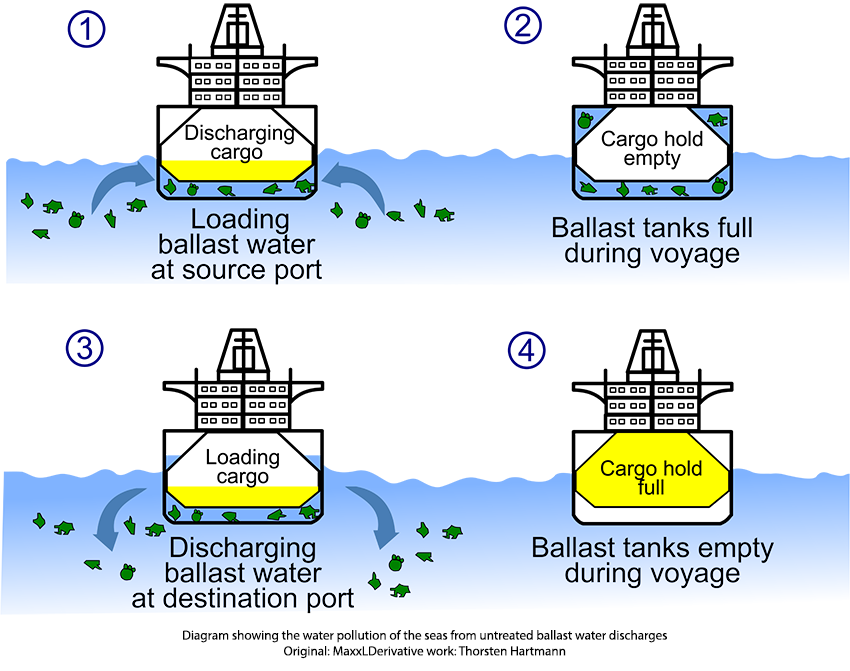

Ballast water is water ships carry in their cargo hold to compensate for changes in cargo loads. This water is often taken on in the coastal waters in one area and discharged at the next port of call, where more cargo is loaded. Ballast water discharge typically contains various biological materials, including non-native nuisance species that can cause extensive ecological and economic damage and seriously impact human health.

Ballast water is water ships carry in their cargo hold to compensate for changes in cargo loads. This water is often taken on in the coastal waters in one area and discharged at the next port of call, where more cargo is loaded. Ballast water discharge typically contains various biological materials, including non-native nuisance species that can cause extensive ecological and economic damage and seriously impact human health.

Serious Incidents of Harm

There have been numerous incidents of ballast discharges causing both ecological and human health harm. Here are a few examples:

- Cholera bacteria: Cholera is a disease caused by eating food or drinking water containing the bacteria, Vibrio cholerae. The disease was largely eliminated in the U.S. in the 1800s with the introduction of modern water and sewage treatment systems. However, it was not eliminated globally. In Peru in 1991, there were 400,000 cases of cholera and over 300 deaths caused by contaminated water.

Vibrio cholerae was found in ballast water in 1991 and 1992 from five cargo ships docked in our ports on the Gulf of Mexico and was also detected in oysters and fish from Mobile Bay, Alabama. It was determined that the bacteria got into the ballast water from a ship’s last port of call, leading the FDA to recommend to the Coast Guard that ballast waters be exchanged on the high seas before ships enter U.S. ports.

- Zebra Mussels: Zebra mussels are native to the Caspian Sea in Asia. They were first observed in the U.S. Great Lakes in 1988 from the ballast water of a transatlantic ship and have spread rapidly from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River and into New York. They caused a reduction in the population of the phytoplankton and zooplankton (microscopic plants and animals) eaten by fish, leading to a significant reduction in native fish and shellfish. Economic losses in the Great Lakes were estimated at $4 billion between 1990 – 2000.

- Asian clam: The Asian clam, native to China, Japan, and Korea, was introduced into the San Francisco Bay in 1986 from a ship’s ballast discharge. Within two years, they spread rapidly across the Bay, reaching densities that crowded out native plants, fish, and shellfish populations. “The early detection of the appearance and spread of the Asian clam in San Francisco Bay makes this one of the best-documented invasions of any estuary in the world.”

Failure to Regulate Leads to Lawsuits

The Clean Water Act, specified that all discharges into the nation’s waters are unlawful unless specifically authorized by a permit. In 1973, the EPA excluded ballast discharges from the permit requirements, stating, “This type of discharge generally causes little pollution and exclusion of vessel wastes from the permit requirements will reduce administrative costs dramatically.”

By the mid-1990s, it was clear that EPA’s exclusion of ballast discharges was fundamentally flawed and led to litigation.

- The first lawsuit, filed in 1999 by environmental groups and water organizations, petitioned the EPA to repeal the exemption and regulate ballast water discharges. The court decision, nine years later, said that the EPA must set permit requirements for ballast water under the Clean Water Act.

- The EPA went to its Science Advisory Board (SAB) which concluded in 2010 that several treatment technologies could meet a standard set by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) [1], but there was no evidence that treatment technologies could meet stricter standards.

- In 2013, EPA issued its ballast water regulations, the same as those of the IMO.

This has triggered almost another decade of litigation, based on the conclusions of the SAB that treatment technologies could not meet stricter standards than the IMO standards.

- A court ruled in 2015 that EPA acted “arbitrarily and capriciously” when it set the regulations for ballast water discharge at the same standard set by the IMO, even though the technology was available to adopt a higher standard.

- A 2017 study re-analyzed the data used by the SAB to conclude that treatment technologies were not available that could meet stricter standards. The authors concluded that the SAB’s analysis was flawed and that available treatment technologies could meet standards 10- to 1000- times more stringent than the IMOs.

- In 2020, EPA published the third set of standards - the same standards rejected by the court in 2015. The basis? The SAB’s conclusions in 2010 rather than the newer findings from the 2017 study.

The letter from the 160 organizations and 34 members of Congress was an effort to exert pressure on EPA to finally regulate ballast water appropriately and highlights one of the EPA’s weaknesses. They are deeply tied to their SAB findings, and bureaucratic inertia leads to slow and, oftentimes, incorrect conclusions. In the case of ballast water discharges, it has led to an outcome that doesn’t reflect the current science behind the issue and misses the fundamental negative impact of ballast water discharges on the environment and human health.

[1] The IMO standard, known as the IMO D-2 Discharge Standard, sets limits on the discharge of two groups of organisms and three indicator microbes