Yes, the nose is often the first point of initial contact with the microbial world. That was certainly the lesson of COVID and helped to explain all those nasal swabbings. The nasal “mucosal barrier,” the lining of the nose, provides a physical barrier through the production of mucus that traps the invades. But as a new research study points out, the mucosa also recognizes the invasion and triggers a group of receptors (Toll-like receptors are their formal names) that initiate our innate immune response.

The research focused not on the mucosa, at least directly, but on the mucus. Little capsules, built with fatty walls, are secreted by the mucosa into the mucus; those vesicles (the capsule's formal name) contain various compounds, including some with antimicrobial properties. Those vesicles enhance the innate antiviral response by sending messages to other nasal cells. They can physically bind with the virus or bacteria to prevent their entry into nasal cells where they can reproduce – “hosting” infection.

Through a series of laboratory experiments, the researchers demonstrated:

- That Toll-like receptors triggered the release of additional vesicles into nasal mucus in a dose-related manner in response to the viral mRNA

- Those vesicles were able to reduce the presence of intracellular viral mRNA, a measure of the degree of infection, for common rhinoviruses but not the coronavirus.

- Those reductions were due to enhanced “small molecules” within the vesicles and by offering up viral binding sites that acted as “decoys” from the actual host receptors.

In an additional series of experiments using nasal tissue from humans, the researchers found that lower ambient temperatures suppressed the release of vesicles into nasal mucus and reduced their antiviral activity. Cold exposure blunts the nose’s initial defense against microbes, in this case, viruses.

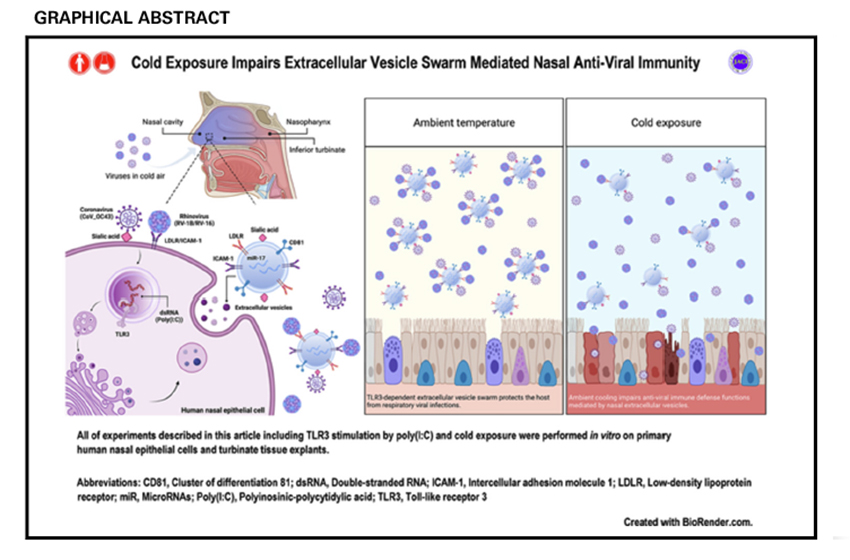

For those of you, and I include myself in this group, that find a visual image helpful in understanding text, here are the researchers’ findings as a graphic.

A few nuggets of knowledge

“Our observations revealed that exposure to cold resulted in increased host susceptibility to respiratory viruses, providing a potential immunologic mechanism for seasonal variation in URIs.”

First, we should be in awe of the complexity of our immune defenses. The deeper we look, the more we see how cells, chemical signals, and physical barriers all interact to keep the outside world out. That this complexity everywhere we look is the result of evolution should give us more humility regarding our roles as “masters of the universe.”

Second, we now see an underlying biological mechanism to explain the environmental factors of temperature and humidity that we have already identified as reasons for the seasonality of upper respiratory infections - and why cold weather makes us more susceptible to colds.

A moment of passing conjecture

If cold does indeed reduce our defenses, can this biological mechanism partially explain how the temperature of our homes and work, where we spend 85% of our time, may foster or guard against "catching a cold?" Could it be that lowering the thermostat to 66 has effects that wearing a sweater or jacket cannot mitigate?

Source: Cold exposure impairs extracellular vesicle swarm–mediated nasal antiviral immunity. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.09.037