Adherence to scientific principles is the standard - along with integrating reliable and valid scientific data. But data morphs, jello-like, during an enfolding, dynamic pandemic. In creating policy, the science must be balanced against economic welfare and conformity with the law and democratic principles – many of which the public doesn’t really understand, parroting politicos whose objectives are prioritized on voter-pleasing and pandering.

Someone who can balance the scientific, legal, and policy ingredients – and speak truth to (political) power is rare–and a hero. We don’t have many such heroes anymore, but once we had: Charles Everett Koop, 13th Surgeon General of the United States from 1982 to 1989 under President Ronald Reagan.

Even supporters of President Reagan will concede his leadership failed and floundered in some public health areas, AIDS and embryo research, to name two. Even Republican leaders, like my personal heroine (and friend), the late Mary Crisp [1], anguished over Reagan’s stance on abortion. During his tenure, Dr. Koop confronted these issues head-on - breaking with the president, advocating for the public welfare even when his personal beliefs were challenged. He also bucked the tobacco industry, publicizing tobacco dangers – but his earliest public intercessions were championing ethics of neonatal care. Where others failed, he succeeded. So how did he do it?

Substance, Style, and Integrity

Koop began his career as an unparalleled expert, which my research discloses is a key determinant of effective leadership: He was a pediatric surgeon who pioneered ground-breaking surgical techniques such as separating conjoined twins. He created the country’s first neonatal surgical intensive care unit and was the first editor of the Journal of Pediatric Surgery.

He also was a model of integrity. As one admirer extolling Dr. Koop’s virtues noted:

“persons of integrity remain true to their vision no matter where they are or who they happen to be with, scrupulously avoiding the chameleonism of those who seem to change their beliefs to fit in, please others, and advance their own interests…. One inspirational example of such integrity [was] C. Everett Koop….”

Plagued by the same insecurities that immobilize us “mortals,” – Koop nevertheless forged ahead, confronting novel issues with fortitude:

“Each day of those early years in pediatric surgery I felt I was on the cutting edge. Some of the surgical problems that landed on the operating table at Children's had not even been named. Many of the operations I performed had never been done before. … At times I was troubled by fears that I wasn't doing things the right way, that I would have regrets, or that someone else had performed a certain procedure successfully but had never bothered to write it up for the medical journals, or if they had I couldn't find it.” - Evertt Koop

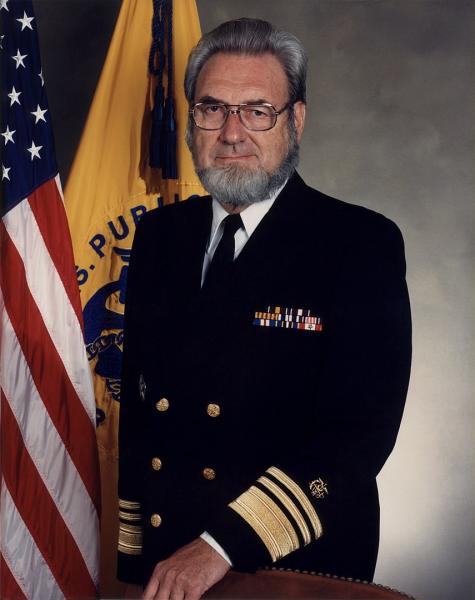

He carried his office with pride, outfitted in his mustache-less beard and full-dress admiral’s uniform, manifesting professionalism and patriotism, emblemizing his station and his role in protecting public health. Whether leaders are born or made, Koop’s experiences shaped his interests, his passions, cemented his concern for others, and his attention to ethics, integrity, and law.

Splitting the Baby – A Solomonic Choice

Separating conjoined twins might seem routine today. But Dr. Koop’s introduction of the process involved novel techniques and issues in medical and religious bioethics. One early story is heart-rendering and a textbook case in medical ethics.

The conjoined twins in question shared a heart. Severing them would result in the certain death of Baby A – with only a possibility that Baby B would survive. Not separating them would be a certain death sentence for both. Is it allowable to kill Baby A so that Baby B has a chance at survival? Did Koop want to try?

The parents were Orthodox Jews who would only consent with the approval of top Rabbinic authorities; much of the nursing staff were Catholic and were similarly on edge. Dr. Koop, a religious Presbyterian, had made the sanctity of newborn life a mantra of his career. They all had reservations. While the rabbis debated and were in constant contact with Dr. Koop, the Church provided permission. Nevertheless, several nurses declined assignment to the surgery. Dr. Koop was also concerned with possible criminal liability for manslaughter.

Arlen Specter (later Senator), representing the hospital, felt that a court order authorizing the surgery was the only way to ensure legal protection. The questions posed by the Judge were almost identical to those posed by the Orthodox Rabbis. After agonizing discussions, Rabbis and Judge agreed. The surgery proceeded more easily than anticipated; Baby B survived. Baby A was buried immediately after the surgery. But three months later, Baby B died of infection and liver failure. She is buried, I believe, alongside her sister.

Baby Doe Amendment

Some years later, in April 1982, “Baby Doe” was born with Down’s syndrome (a chromosomal abnormality that produces mental retardation) and, in this case, esophageal atresia, the separation of the esophagus from the stomach rendering the newborn unable to ingest food. The obstetrician told the parents their child had a 50 percent chance of surviving the atresia surgery. Still, he said, even if surgery were successful, their child would remain severely retarded and require life-long care. The family’s physician and a hospital pediatrician disagreed and demanded immediate surgery. The parents refused. The hospital's attorney and attorneys representing couples prepared to adopt the baby went to court to have him declared a neglected child under Indiana's Child in Need of Services statute and to require court-ordered medical treatment. They lost the case, and the child died before the Supreme Court could rule on the matter.

The death of Baby Doe triggered a fierce controversy over:

- the right of infants with congenital disabilities to medical treatment

- the right of the government to intervene in the relationship between doctors and their patients

- parental rights in decisions involving the future of their children.

Conservatives, pro-life activists, and individual physicians and health care providers--including the hospital nurses --condemned the decision not to operate on Baby Doe as infanticide. Koop, likely primed by the earlier Baby A and B controversy, and now Surgeon General agreed. While not directly involved in the case, he had performed almost 500 surgical atresia repair operations with nearly 100% success.

Koop became a public advocate for saving the youngest and weakest patients. As chief public health officer, he felt compelled to speak out against the decision made by Baby Doe’s parents. Soon after, a similar case concerning a girl born with spina bifida surfaced. Here Koop interceded directly, but the delay in surgery was severely detrimental to the child.

Koop argued that as the government had the right to override parental wishes established by truancy, child abuse, and immunization laws, it should extend to the protection of children with congenital and other disabilities. The moral and religious tone of Koop's stance made it suspect to many liberals and civil libertarians. Nonetheless, he felt the nation's medical and legal system had failed to protect Baby Doe. both as a human being and citizen, against neglect and discrimination.

Koop and the Department of Health and Human Services drew up plans to prevent future Baby Doe crises – struck down by the courts because they infringed on the autonomy of doctors and parents. But in October 1984, due in large measure to support by Koop, Congress enacted the Baby Doe Amendment, the culmination of that extended, often bitter debate over the medical rights of newborns, the extent of government authority, the meaning of citizenship, and the value of human life.

The amendment extended the definition of child abuse to include the denial of fluids, nutrition, and medically indicated treatment for infants with congenital disabilities and required states to implement procedures for reporting and investigating such cases of neglect.

Similar concerns might be helpful today to address the medical treatment of disabled adults, who are similarly shunted aside when medical professionals deem surgical intervention on their behalf would result in “insignificant improvement” compared to the same outcomes in the functionally abled. Who is there to speak for this segment of the population?

Koop didn’t shy away from issues imbued with controversy. I will have more to say about Koop’s speaking truth to power.

[1] As Mary Dent Crisp, a pro-choice Republican, Co-Chairwoman of the Republican National Committee, tells it, she resigned on national television when learning President-elect Reagan was reversing his stance on abortion.