Caffeine, cinnamon, or licorice are all foods or substances considered GRAS. Helium, hydrogen peroxide, or propane - all are considered GRAS substances when directly added to food.

What is “general recognition” of safety? The FDA Commissioner, in the 1958 hearings for the Food Additives Amendment, explained it in this homespun way:

“Proof of the pudding is in the eating.”

This is a very different regulatory mindset from today’s regulatory environment.

Background

Food manufacturing is a huge industry, with an estimated revenue of $764.5 billion in the U.S. in 2022. The GRAS rule is an example of old regulation (1958), which allows the private sector to self-regulate; i.e., the food industry is given wide latitude not to undergo intensive testing on every substance in their products. Although there have been many changes in the rule over time, the basics remain the same – if a substance is considered “generally safe,” it does not require intensive FDA review.

The food we eat includes a wide array of substances. For example, a box of Stove Top stuffing mix contains the following ingredients: enriched wheat flour (wheat flour, niacin, reduced iron, thiamin, mononitrate (Vitamin B1), riboflavin (Vitamin B2), folic acid), high fructose corn syrup, onions, contains less than 2% of hydrolyzed soy protein, salt, monosodium glutamate, yeast, unesterified soybean oil, cooked chicken, spice, celery, parsley, chicken broth, garlic, turmeric (color), natural flavor, with BHA, BHT and rosemary extract as preservatives.

The food we eat includes a wide array of substances. For example, a box of Stove Top stuffing mix contains the following ingredients: enriched wheat flour (wheat flour, niacin, reduced iron, thiamin, mononitrate (Vitamin B1), riboflavin (Vitamin B2), folic acid), high fructose corn syrup, onions, contains less than 2% of hydrolyzed soy protein, salt, monosodium glutamate, yeast, unesterified soybean oil, cooked chicken, spice, celery, parsley, chicken broth, garlic, turmeric (color), natural flavor, with BHA, BHT and rosemary extract as preservatives.

The GRAS rule allows food manufacturers with new products to examine all the ingredients and see which ones are already considered GRAS (these are published in the Federal Register). These substances do not have to undergo an FDA review. For the other ingredients, the food manufacturer must either: 1) submit detailed information on the substance, including chemistry, consumer exposure, migration within food, and conditions of use to the FDA, or 2) submit a notice to the FDA explaining why the substance should be considered GRAS, and if approved by the FDA, it can be used in the food product.

GRAS

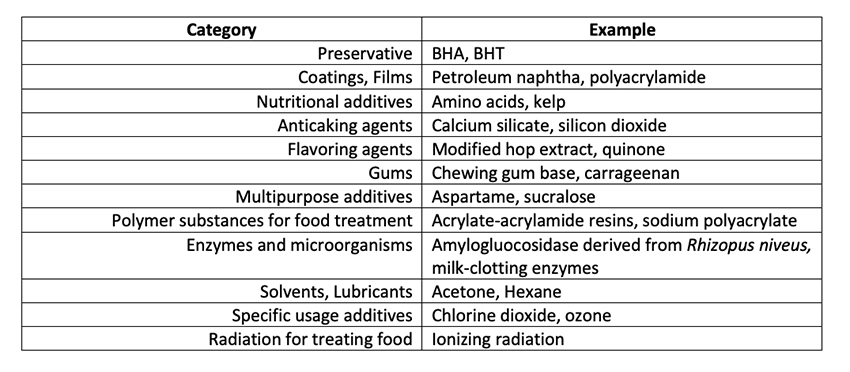

Substances designated GRAS are grouped into major categories:

A GRAS-designated substance often includes specific allowable amounts in foods.

Substances can be removed from the GRAS list if FDA determines, from post-marketing, if it is found to be unsafe. Cyclamates were removed in 1969 after they were reported to be carcinogenic; six flavoring agents [1] were removed in 2018 because they caused cancer in laboratory animals.

Some interesting substances designated GRAS include:

- Hydrogen peroxide is used to treat a variety of foods, including milk, for use during the cheesemaking process, whey, dried eggs, tripe, herring, and wine.

- Helium is used in food packaging to prevent spoilage and is allowed at levels not to exceed current good manufacturing processes.

- Licorice is allowed in baked foods, candies, alcoholic beverages, non-alcoholic beverages, chewing gums, and herbs and seasonings at concentrations ranging from 0.05% in baked foods to 16% in hard candies;

- Caffeine is GRAS when used in cola-type beverages in accordance with good manufacturing processes.

Evolution of GRAS

Over time, there has been a desire to make the GRAS rule more rigorous and transparent.

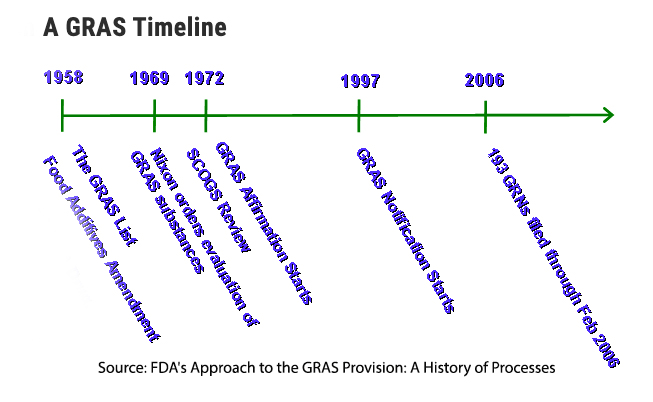

Although food regulation began in 1906 with the Pure Food and Drug Act, the GRAS list started in 1958 with the Food Additives Amendment. In 1958, FDA considered 180 substances to be GRAS, with no transparency as to how that was determined. The food industry considered many substances to be GRAS that were not on the 1958 list and wrote the FDA asking them for an opinion as to the GRAS status of their substance. The FDA opinion was available to the requestor - again, no transparency here.

In 1969, the “cyclamates” were removed from the GRAS list because they were reported to be carcinogenic. There was a great public outcry over cyclamates and food safety, in general. To satisfy the public concern over exposure to unsafe ingredients, President Nixon ordered a thorough review of the GRAS rule, resulting in the 1972 formation of the Select Committee on GRAS Substances (SCOGS), scientific consultants hired to review and evaluate each of the GRAS substances. By 1982, SCOGS had submitted opinions on the health aspects of over 400 substances. [2]

The FDA reviewed the SCOGS opinions, and industry could submit a “GRAS Affirmation Petition” for substances they wanted to be designated GRAS. With FDA concurrence, they would be added to the GRAS list. In 1997, FDA changed the procedure putting the burden of proof of safety on food manufacturers. By the end of 2006, 193 of these “GRAS Notices” were filed, with the FDA responding, on average, within 162 days.

In 2016, the FDA issued regulations clarifying the GRAS Notification process, including the procedure. The rule specified that for a substance to be considered GRAS, there must be:

- Common knowledge throughout the scientific community that the substance is not harmful under conditions of its intended use, based either on scientific procedure or common use of a substance before 1958, and

- Scientific procedures must report accepted scientific data, which ordinarily are published, which may be corroborated with unpublished scientific data.

Current Tensions with GRAS

The GRAS rule, very limited initially, has evolved to become more rigorous but still provides the food industry with a high degree of freedom, creating friction with consumer and citizen advocacy groups.

The major criticism, as outlined in Consumer Reports, is that the GRAS rule risks consumers by allowing food manufacturers to bypass crucial safety checks. They believe that the food industry is designating more and more food additives as GRAS without carrying out sufficient scientific tests and without giving notice to the FDA.

Additionally, there are concerns that the GRAS designation of substances, such as high fructose corn syrup and corn sugar, does not inform consumers as to the nutritional value of these substances. Consumers may mistakenly believe that the GRAS designation is a “seal of approval” regarding its nutritional value from the FDA.

While some criticisms of the GRAS rule are valid, the rule has worked quite well over more than 50 years. It allowed food manufacturers to develop new food products without undergoing a lengthy regulatory process for the ingredients already known to be safe. To do otherwise would quickly overwhelm the FDA resources and stifle food innovation. In turn, this would lead to higher food costs and perhaps fewer new foods, as manufacturers decided it was not worth the cost and time of a lengthy FDA review.

This is challenging because the food industry moves quickly depending on consumers’ changing desires and tastes. In my opinion, the GRAS rule works because the industry recognizes that another “cyclamate” incident where the public mistrusts the safety of their food would dramatically expand federal oversight and regulation.

[1] Synthetically-derived benzophenone, ethyl acrylate, methyl eugenol, myrcene, pulegone, and pyridine.

[2] Many of which are now found on the SCOGS database.