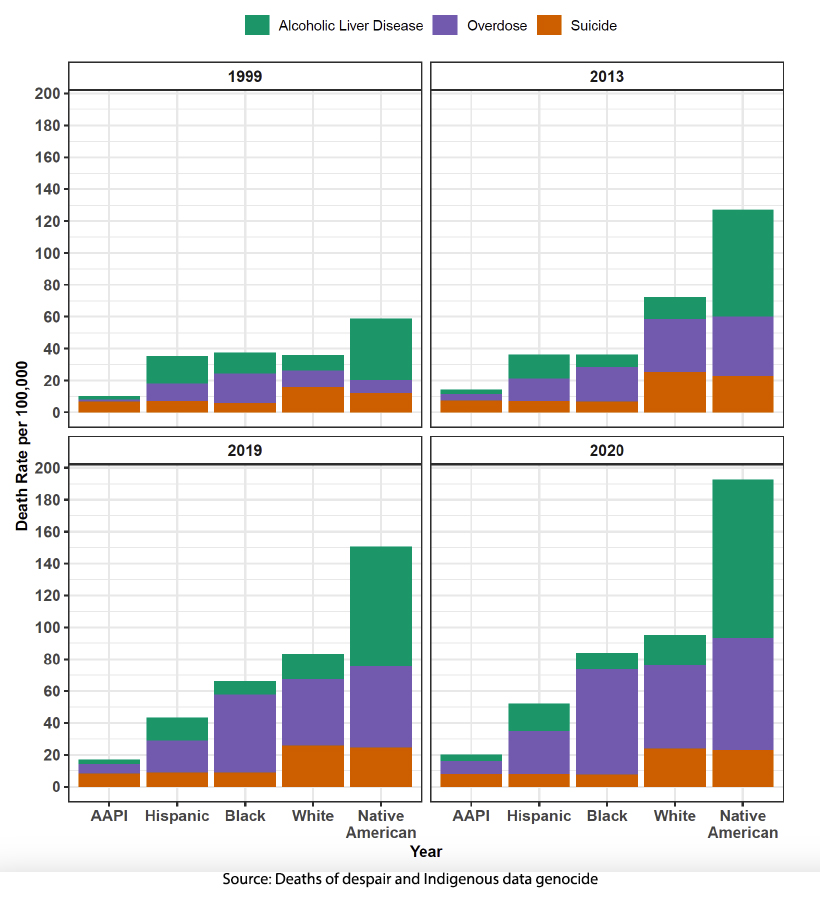

The underlying explanation is that deaths of despair signal the end of hope to those Americans who have seen their jobs, homes, and futures vanish due to the forces of globalization and capitalism's hunger for growth at lower and lower costs. The viewpoint, published in The Lancet, seeks to remind us that this has been the fate of native, indigenous Americans since Manifest Destiny. Here are the data for the group most at risk, the middle age, 45-54-year-old males.

It is evident that native Americans have led the way in deaths of despair for many years.

It is evident that native Americans have led the way in deaths of despair for many years.

A Woke Moment

The authors introduce a new phrase, at least to me – "data genocide,” by which they mean “the erasure of data attesting to deleterious health outcomes for Native American communities.” Many would argue that this is a carefully constructed woke word choice that mingles the absence of information with the historical record of our treatment of Native Americans. At the least, it is designed to capture attention. But we do a disservice to the data and what we might learn by focusing on the phrase, not the underlying information.

Let the Data Speak

The authors suggest that we improve our data collection by asking the stakeholders, in this case, Native Americans, to participate in “collection, maintenance, and sharing of community data.” Having everyone “sit at the table” remains an aspirational goal because, as the authors note,

“Given the historical wrongdoing, many Native American people might not wish for data describing them to be collected, analysed, or disseminated outside of their communities.”

Shades of Tuskegee; might we add Manzanar and our treatment of Asian American citizens?

Their other suggestion is that in discussing national issues, “Native American people should be specifically enumerated and not categorized or labeled as other,” but, to my mind, that misses an important point. And it is here that I anticipate pushback. I think we might be better served in understanding deaths of despair, if only partially, by enumerating by caste – a combination of income and ethnic identity, rather than ethnicity alone. America likes to consider itself along lines other than caste, but that is us denying the truth.

Many " lenses " might be used to view this deadly crisis; focusing on ethnicity, income, or their entanglement will provide only partial answers. Moreover, some of those lenses have irrelevant political agendas. Deaton and Case, who brought the term to our national consciousness, explain,

“…those in despair are in despair because of what is happening to their own lives and to the communities in which they live, not because the top 1 percent got richer.”

The researchers end by writing,

“This erasure of contemporary Native American presence and visibility plays a role in allowing health inequalities to go unchecked by depriving extreme disparities among Native American communities of the intense media and public attention that they deserve.”

That too, misses the mark; the problem of deaths of despair needs not just more attention. It requires action. Unfortunately, our leaders are too busy investigating one another to have time to attend to us.

Source: Deaths of despair and Indigenous data genocide The Lancet DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02404-7