The first city in the US to routinely disinfect water was Jersey City, New Jersey, in 1908. Water disinfection is a broad term that includes all methods of killing microbes in drinking water. The primary disinfection methods are chlorine, ozone, ultraviolet light, and chloramines.

Waterborne Diseases Today

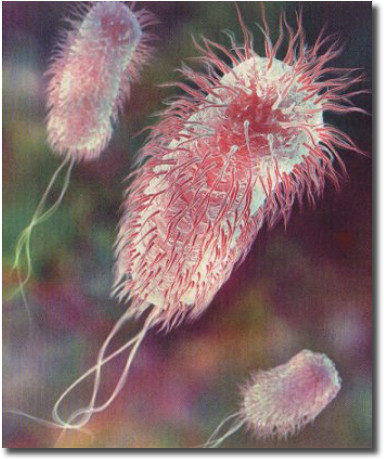

Although waterborne diseases have been greatly reduced in the US, they have not been eliminated. Most waterborne diseases today are not from inadequate disinfection at drinking water treatment plants but from microbes that grow and spread in the plumbing inside buildings and in recreational water venues such as swimming pools and hot tubs. These microbes grow in biofilms (bacterial build-up) that attach to the walls inside pipes, pools, and plumbing fixtures.

In addition, many illnesses today are not from direct drinking water but from breathing in tiny droplets of contaminated water. Legionella, which causes Legionnaires’ disease, is an example of this type of microbe.

It is challenging to obtain an accurate count of waterborne disease illnesses and deaths because states report waterborne diseases to the CDC through a variety of surveillance systems, none of which adequately capture all waterborne disease illnesses and deaths. In some instances, outbreaks are investigated by local and state public health officials and not reported to the CDC. Some of the most prevalent waterborne diseases are not even on the CDC’s National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, including Nontuberculous mycobacteria, Otitis externa, and Pseudomonas, which monitors about 120 diseases.

Until recently, there were no national counts on the number of deaths from waterborne pathogens in the US. A 2017 article documented 6,301 deaths from 2003 – 2009 from 13 waterborne disease infections in the US [1]. A 2021 article examined US data from 2000- 2015 and estimated that there were 118,000 hospitalizations and 6,630 deaths due to waterborne illnesses.

Legionnaires’ Disease is probably the most well-known of all the waterborne diseases discovered after an outbreak of pneumonia among American Legionnaires attending a convention in Philadelphia. The cause was determined to be Legionella bacteria that were breeding in the cooling towers of the hotel’s air conditioning system, which then spread throughout the building. Legionnaires’ disease is a severe respiratory illness characterized by fever, cough, chest pains, and diarrhea. Legionella bacteria can also cause Pontiac fever, a flu-like illness usually self-limiting and less severe.

Legionella is found in fresh water and rarely causes illness. However, in plumbing systems, Legionella may multiply and cause disease. People become infected when small droplets of water containing the bacteria get into the air, and people breathe them in. In 2014, there were an estimated 995 deaths from Legionnaires’ disease.

The Grim Reapers

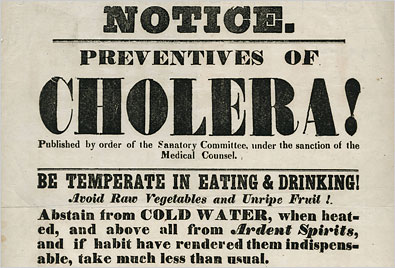

Typhoid fever and cholera are the two diseases responsible for most global deaths. Both are rare in the US.

Typhoid fever is caused by the bacteria Salmonella typhi found in contaminated food or water. While related, this is not the same bacteria that cause Salmonella poisoning (salmonellosis) from food. In the 1900s, there were tens of thousands of cases of typhoid fever in the US; today, less than 400 cases per year are reported, most occurring among international travelers. Despite an available vaccine, typhoid fever has remained a global problem, with about 11 million - 20 million cases annually and 128,000 - 161,000 deaths yearly. Most of these cases are in impoverished countries in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Cholera caused by the bacteria Vibrio cholera results in acute and profound diarrhea. It has been around for centuries but rapidly spread worldwide in the 19th century and was first detected in the US in 1832. There have been four worldwide cholera pandemics between 1832 and 1875. A fifth (1891-1896) and sixth (1899-1923) pandemic did not affect North America and Western Europe due to advances in water sanitation. According to the WHO, the seventh and current pandemic began in Indonesia in 1961 and has affected 120 countries, largely impoverished nations, primarily occurring after natural disasters such as earthquakes, droughts, and floods. Worldwide, there are an estimated 1.3 – 4.0 million cases of cholera and 21,000 – 143,000 deaths annually, underscoring the importance of clean drinking water. Cholera is very rare in the US today (estimated at up to five cases annually), with most cases occurring from international travel or eating contaminated food.

Cholera caused by the bacteria Vibrio cholera results in acute and profound diarrhea. It has been around for centuries but rapidly spread worldwide in the 19th century and was first detected in the US in 1832. There have been four worldwide cholera pandemics between 1832 and 1875. A fifth (1891-1896) and sixth (1899-1923) pandemic did not affect North America and Western Europe due to advances in water sanitation. According to the WHO, the seventh and current pandemic began in Indonesia in 1961 and has affected 120 countries, largely impoverished nations, primarily occurring after natural disasters such as earthquakes, droughts, and floods. Worldwide, there are an estimated 1.3 – 4.0 million cases of cholera and 21,000 – 143,000 deaths annually, underscoring the importance of clean drinking water. Cholera is very rare in the US today (estimated at up to five cases annually), with most cases occurring from international travel or eating contaminated food.

EPA Regulations

EPA has three main rules to control microbes in public drinking water systems [2]

Revised Total Coliform Rule: Establishes a maximum contaminant level (MCL) for Escherichia coli (E. coli) in drinking water. E. coli are a large group of bacteria that, when found in water, are a strong indicator of sewage or animal waste contamination and indicate that other waterborne microbes may be present.

Revised Total Coliform Rule: Establishes a maximum contaminant level (MCL) for Escherichia coli (E. coli) in drinking water. E. coli are a large group of bacteria that, when found in water, are a strong indicator of sewage or animal waste contamination and indicate that other waterborne microbes may be present.- Surface Water Treatment Rule: Requires all drinking water systems that use surface water to use disinfection resulting in 99.9% removal of viruses, Giardia, and Cryptosporidium. Giardia and Cryptosporidium are both protozoa that cause gastrointestinal upset, characterized by diarrhea, stomach cramps, and nausea.

- Ground Water Rule: Groundwater is usually cleaner and contains fewer contaminants than surface water, and not all drinking water systems using groundwater require disinfection. This rule requires groundwater systems to identify if they are susceptible to fecal contamination and, if they are, to disinfect and take other actions to prevent the growth of viruses.

Water treatment plant operators must carefully manage the amount of disinfectants, such as chlorine, that they add to water. This is because additional EPA regulations limit disinfectant by-products, the chemical compounds formed when chlorine or other disinfectants react with organic compounds in water, creating hazardous chemicals.

What to Do?

There are no easy fixes to eliminate waterborne diseases today. The US has made tremendous progress in eliminating waterborne diseases. There needs to be better data and non-traditional solutions to build on our progress.

For public water systems, the EPA regulations do a good job of preventing contamination at the water plant. If you own a private well, you should be testing for microbial contamination. However, the problem is that microbes often hide in plumbing systems and cooling towers beyond the reach of traditional regulations.

Data is essential to develop solutions. We don’t even know the extent of the problem! The available data is a patchwork of information drawn from numerous sources. The CDC needs to work with the states and local public health agencies to develop a national collection system for waterborne diseases.

Additionally, there needs to be a mix of public-private partnerships to address drinking water contamination issues beyond the treatment plant. For example, the CDC has developed a set of recommendations for offices and hospitals with concrete steps to reduce the spread of Legionella and other microbes spreading within their buildings. These programs need to be expanded to include hotels, recreational facilities, and other establishments that often unknowingly become sources of waterborne disease.

[1] The microbes included: Campylobacter, Cryptosporidium, E. coli, Giardia, Hepatitis A, Salmonella, non-typhoidal Shigella, Free-living amoebae, Legionella (Legionnaires’ Disease), Nontuberculous mycobacteria, Otitis externa, Pseudomonas Vibrio

[2] These rules do not apply to private wells and other non-public drinking water systems.