As Stat reports, Senators Manchin and Markey have written to the FDA asking them to stop the study. This is not Senator Manchen’s or Markey’s first time writing on ending enrichment enrollment randomized withdrawal (EERW) studies of opioids. Before jumping into what they do get wrong, it is time to take a deeper dive into EERWs.

Clinical Trials

How you measure something often impacts what you find and conclude. With opioid studies, what we might consider “traditional” randomized controlled trials (RCT), individuals with pain are given pain medication or placebo. They are the parallel studies in the illustration. Cross-over studies, where participants are given first a course of pain medication or a placebo, and then half-way through the study, medication and placebo are switched, have shown a greater response to opioids than those parallel studies. EERWs, another form of an RCT, and the one being questioned demonstrate an even more significant response to pain medications. I will return to EERWs in a moment.

All RCTs have problems beginning with participant selection bias; there is “limited patient willingness” to participate in a placebo-controlled trial where they may get the placebo. This cannot be remedied by a post-market trial, so the required FDA post-marketing studies of opioids have been hampered by the inability to attract a sufficient and diverse population.

Another bias in RCTs is how “blinded” the placebo or comparison arm is to their assignment. When a drug, like an opioid, has a substantial subjective effect, study participants may “know” which group they are in, and that knowledge may bias the results. There is also an ethical concern: how long should you withhold care or relief from the placebo participants? Following the dictum to "do no harm," the ethical dilemma usually results in researchers conducting short-term studies measured in weeks, not months.

Finally, based on the participants selected and the study’s length, there is a concern about how generalizable a study can be – can it apply to a wider population? The lack of generalization found in all RCTs helps explain why a drug or device may perform much better in its clinical trial than in the real world.

While enrichment has its costs, there are also benefits. For many chronic conditions, like hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and pain, finding the optimum treatment is often “trial and error.” Enriching the enrollment of participants is particularly useful when looking for small effects of treatment or when considering widely different populations. At the risk of divisiveness, consider how much more we might trust the COVID-19 vaccine studies if one was enriched with those over 65 with multiple co-morbidities or young men aged 20 to 30.

What is an enrichment enrollment randomized withdrawal trial (EERW)?

“EERW studies answer the question of whether there is a group of patients in a population who respond to a drug therapy and lose the effect when withdrawn.”

RCTs can be “enriched,” making their ability to identify small but clinically relevant effects more apparent. The initial publication on EERWs as an RCT design dates back to a paper written in 1975 by two employees of Janssen Pharmaceuticals. [1] EERWs enrich themselves by deliberately reducing the variability (heterogenicity) of the participants; in exchange, the generalizability of the findings is more restricted. A more subtle distinction is that in traditional RCTs, one looks at whether participants respond to treatment; in a withdrawal study, one looks at how participants respond to the drug's absence. If a drug is sufficiently effective, its withdrawal will be identified relatively quickly. That reduces the time necessary to study a drug and the ethical concern over harm to those in the placebo arm.

The study

The study in question is a post-marking review (PMR) mandated at the time of approval for long-acting, extended-release morphine to treat chronic pain. Work on this PMR began in 2013 and included a previously failed clinical trial, which led the researchers to use an EERW. That is why the Senators are incorrect in stating, "This study is intended to specifically look at the use of EERWs to approve new opioids.”

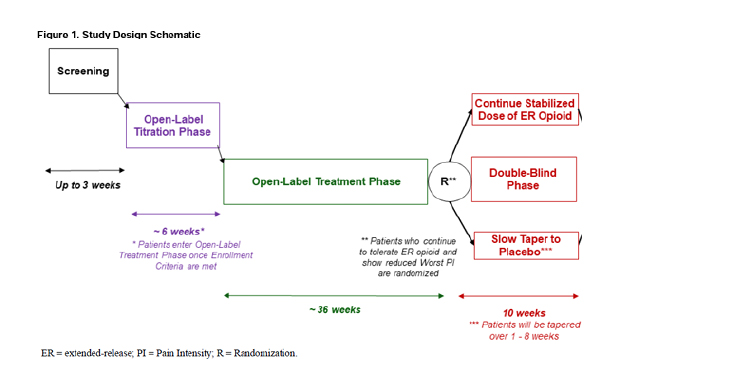

Much of the design of this study was informed by the previous attempt, where they could not recruit sufficient participants. Here is a schematic of the flow of patients through the study.

- Screening – The participant pool are patients with daily chronic pain for more than 3 of the last six months, not receiving long-acting medications, and inadequate pain control despite the use of short-acting opioids, as well as non-opioids, e.g., anti-inflammatories and non-pharmacologic therapies.

Chronic pain may include low-back pain, osteoarthritis of the hip or knee, painful peripheral neuropathy (including that found in patients with diabetes), and pain related to cancer therapy in patients in remission.

- Open-Label Titration – Under the care of the patient’s physician, they are titrated to a maximum of 240mg/d of a single dose of an oral, long-acting, extended-release morphine to achieve efficacy. Morphine was chosen as a widely prescribed treatment. However, it is important to note that the morphine upper limit is 240 MME, far greater than the usual arbitrary limits of 90 Morphine Milligram Equivalents (MME). Patients continue their other adjunctive care, e.g., yoga, physical therapy, the use of NSAIDs, etc. [2]

The Senators note that a study commissioned by the FDA was concerned that in this titration phase, “all participants [are exposed] to opioids in the first phase of the study.” But none of the study participants are opioid naïve; in fact, all of them have been using short-acting morphine for at least three months.

- Open-Label Treatment – The use of long-acting morphine is continued as long as the participant and investigator believe there is meaningful improvement and the morphine is tolerated. During this interval, the patient’s physician may adjust the dose, within the study’s parameters, to maintain a “≥30% reduction in past 7-day” pain scores. Those unable to maintain improvement or tolerate the medication are dropped from the study.

The Senators are correct in noting that by removing “participants who do not tolerate the negative side effects of the opioids,” adverse effects in the study group will be underestimated. But this is largely irrelevant since information on those removed provides some of that data, and the purpose of the study is the efficacy of long-acting morphine, not its safety profile. In keeping with the appropriate standard care for patients with chronic pain, the use of rescue medications for acute exacerbations of pain is allowed from this point onward in the study [3].

The open-label treatment period creates an enriched homogenous population of individuals clinically responsive to the treatment without adverse consequences. It has created a real-world population of patients with chronic pain who have failed the recommendation of the CDC, “When starting opioid therapy for acute, subacute, or chronic pain, clinicians should prescribe immediate-release opioids instead of extended-release and long-acting (ER/LA) opioids.”

- Randomization - Participants who continue to tolerate ER opioids and show a reduction in their worst pain intensity are randomized to continue or begin a structured tapering from the long-acting morphine.

- Blinded taper – over 1 to 8 weeks, depending upon entry dose of morphine ER; higher doses result in longer tapers. This is when some degree of “unblinding” may occur, especially if patients develop “acute withdrawal” from their opioid dose and require rescue medications. This is a valid concern. The researchers note that this rarely occurs in EERW studies and hope that the more gradual taper, lengthened by a greater baseline dose of opioids received by the participant, will further reduce this concern.

- Follow-up – continued attempt to follow all patients for an additional two months.

- The titration run-in period lessens the risk of patients dropping out of a study, creating a more consistent, at least similar-looking, group to study.

- Patients will be more inclined to participate in a long-term study because their possible exposure to being in the placebo arm is significantly reduced, and once the study is completed, they may restart opioid therapy.

The primary objective is to create a feasible study to evaluate the persistence of analgesic efficacy in this clinically relevant patient population. There are several important secondary objectives [4], notably trying to identify opioid-induced hyperalgesia, an effect that many pain patient advocates have refused to accept as real.

The Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH) Sub Study

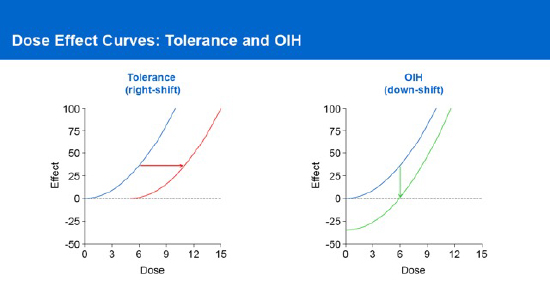

Let us begin by defining hyperalgesia – an increased sensitivity to pain when a person becomes more sensitive to painful stimuli than what would typically be expected. The incidence of OIH is thought to be relatively low in patients with chronic pain, but the actual value remains unclear. Moreover, OIH appears much like opioid tolerance, illustrated in the diagram, where there is a need for increasing amounts of medication to maintain the same effect.

Let us begin by defining hyperalgesia – an increased sensitivity to pain when a person becomes more sensitive to painful stimuli than what would typically be expected. The incidence of OIH is thought to be relatively low in patients with chronic pain, but the actual value remains unclear. Moreover, OIH appears much like opioid tolerance, illustrated in the diagram, where there is a need for increasing amounts of medication to maintain the same effect.

Dose escalation is a key diagnostic criterion in defining a substance use disorder. Is it possible that some of the dose escalation seen in some patients, taken as “evidence” of the harmful addictive nature of opioids, is OIH?

The OIH study will consider a subset of 200 patients evaluated throughout the study for changes in pain sensitivity, as measured by a qualitative assessment of the “spread” of pain and an objective, quantitative measure of their response to thermal pain. Patients with dose escalation because of increasing pain sensitivity will be differentiated by the objective measure of thermal pain. Those with OIH will respond more significantly to thermal pain; the opioid-tolerant will not demonstrate that objective response.

Let's return to Senators Markey and Manchin.

“an FDA-commissioned report noted fundamental flaws in EERW design.”

– Senators Markey and Manchin

However, those flaws were variations of those found in all RCTs. And that commissioned report had more to say,

“The 2020 [FDA to industry] guidance document suggests integrating inclusive trial practices, such as enrichment approaches that would lead to enrolling representative samples of the populations that are expected to use the drugs. … Inclusive trial practices are important for fully understanding a drug’s real-world benefit-risk profile.”

Cherry-picking quotes is not limited to scientists.

The study can generate “high-level” evidence of the efficacy of long-acting opioids in a real-world population of patients with chronic pain. It will evaluate safety and provide insight into separating opioid-induced hyperalgesia from tolerance, perhaps reducing the belief that high doses of morphine result in addiction.

[1] For those who see conflicts of interest based solely on funding, this is already a red flag in the permanent record.

[2] Medical marijuana, illicit drugs, and alcohol are not allowed.

[3] Specifically, 3 gm of acetaminophen or up to 30mg of short-acting morphine are allowed

[4] They include identifying potential predictors of opioid analgesic response, the changes in physical function, anxiety, and depression in this group, and evaluating the therapy's safety.

Sources: Markey and Manchin urge FDA to stop its study of opioids for chronic pain Stat

Systematic review of enriched enrolment, randomised withdrawal trial designs in chronic pain

a new framework for design and reporting Pain DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000088

A comparison between enriched and nonenriched enrollment randomized withdrawal trials of opioids for chronic noncancer pain Pain Research and Management DOI: 10.1155/2011/465281

Extended-Release/Long-Acting Opioid Analgesics Industry Consortium: Opioid Post marketing Requirements Consortium Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products Advisory Committee Meeting

Enrichment Strategies for Clinical Trials to Support Determination of Effectiveness of Human Drugs and Biological Products Guidance for Industry FDA

Transcript, Speaker presentation, and Opioid Post Marketing Requirements Consortium presentation of Anesthetic And Analgesic Drug Products Advisory Committee Meeting April 19, 2023