This, in essence, is the lament of neurologist Adina Wise over the game and spectator sport of football, now known to cause serious injury. Focusing on brain injuries known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), resulting in dementia, depression, and suicide caused by repetitive blows to the heads of players, both amateurs, and professionals, Dr. Wise decries the adulation of the fans, which enables the game to continue. With the football calendar scheduled for release in less than a month, perhaps it’s time to revisit the issue.

How serious is chronic traumatic encephalopathy?

Very. These injuries, including loss of memory and death, manifest years after exposure. But they are notoriously difficult to diagnose or prove. Nevertheless, CTE is both dangerous and dose-related in terms of frequency of exposure, duration, and intensity of brain blows suffered during the game. [1]

According to the National Institutes of Health

“CTE is a delayed neurodegenerative disorder that was initially identified in postmortem brains and, research-to-date suggests, is caused in part by repeated traumatic brain injuries.”

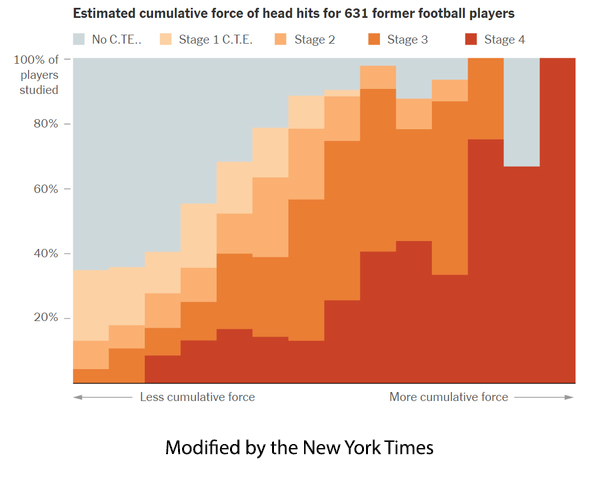

A New York Times article describes the odds of developing CTE as increasing exponentially with more cumulative force to the head, notably from American tackle football. A study in the Annals of Neurology found that:

“For every year of absorbing the pounding and repeated head collisions that come with playing American tackle football, a person’s risk of developing chronic traumatic encephalopathy)… increases by 30 percent. And for every 2.6 years of play, the risk of developing CTE doubles.”

Actual proof of a causal connection (which can only be done experimentally and hence is unethical) is elusive. Even medical proof of injury is nigh impossible, as it can only be conclusively established on autopsy. Nevertheless, a causal connection between Repetitive Head Injuries (RHI) and neurological consequences has been established by independent researchers, along with a strong dose-response (more force – worse disease).

Actual proof of a causal connection (which can only be done experimentally and hence is unethical) is elusive. Even medical proof of injury is nigh impossible, as it can only be conclusively established on autopsy. Nevertheless, a causal connection between Repetitive Head Injuries (RHI) and neurological consequences has been established by independent researchers, along with a strong dose-response (more force – worse disease).

CTE and the Law

The implications are both public health-related and legal, beginning with our children, triggering informed consent questions: Are young children who play fully informed of the repercussions? Can the youngster fully consent? Can their parents consent for them? How much influence does peer pressure play?

“ Medico-legally, millions of children are exposed to RHI through sports participation; this demographic is too young to legally consent to any potential long-term risks associated with this exposure.”

I’ve written about CTE before, but more has come to light in the last two months. In 2012, the NFL concussion class action lawsuit (claiming negligence) was filed by 4500 retired players and their families, resulting in headgear and rule changes. A billion-dollar settlement was reached in 2015. But in late January of this year, it emerged that the NFL is trying to sidestep their responsibilities, making it exceedingly difficult for the injured to establish their claims. An expose published in the Washington Post found that:

“[The NFL] routinely fails to deliver money and medical care to former players suffering from dementia and CTE, resulting in the league saving hundreds of millions of dollars.”

After combing through some 15,000 pages of documents, The Post found that players diagnosed with dementia by their personal doctors were denied recovery by NFL physicians who "simply overruled physicians who actually evaluated players," attributing their dementia to something game-unrelated, like depression and sleep apnea.

“At least 14 players "failed to qualify for settlement money or medical care and then died, only to have CTE confirmed via autopsy."

The NFL will only issue dementia compensation upon a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. However, PET imaging shows that cognitive impairment in football (college and professional) players is unassociated with Alzheimer’s biomarkers, notably amyloid plaques.[2] Recent studies confirm that the higher standards the NFL uses for compensation are not borne out by PET imaging.

The PET research, however, doesn’t confirm the causal relationship between football-induced trauma and CTE. That is done via comparative autopsy studies by Boston University’s CTE Center. Not surprisingly, those on the hook for compensation, the NFL’s insurers, are now engaging in denial of the football-CTE connection entirely.

A March 22 report asserted, "In a bid to avoid reimbursing the NFL, insurers deployed three medical experts to argue that there’s no scientific CTE evidence.” Other scientific experts disagree. One group noted that “Exposure to repetitive head impacts (RHI) in American football players can lead to cognitive impairment and dementia due to neurodegenerative disease, particularly chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).”

The battle rages on. No one knows the precise physiological mechanism responsible for the signs and symptoms of the syndrome, which will be challenging if at all possible, to prove. Boston University’s CTE Center is pursuing the SAVE study to evaluate the effects of repetitive head impacts. [3] But we can expect more litigation by the insurers and continued recalcitrance by the NFL in payout over claims. So, what do we do while the legalities resolve themselves?

Cognitive Dissonance

Dr. Wise’s admonition focuses not on the game or its rules but on preventing consequential injuries and human decision-making, including the viewing, that encourages these harmful activities to continue.

“In the 20-plus years since neuropathological evidence of this disease was first found in the brains of NFL players, I have scarcely heard anyone suggest that, as a result, they plan to reconsider their fandom.”

- Dr. Adina Wise, Neurologist

She attributes this “illogical” decision-making process to cognitive dissonance, the mental difficulties in simultaneously holding two competing beliefs in mind. She explains that when faced with two conflicting actions, we change our preferences -- simply by making the choice. Here’s her example: “I wish to mitigate suffering secondary to neurological illness” and “Go Steelers!” Scientific studies have shown that “The mere act of making a choice can change self-reported preference as well as its neural representation in the brain,” i.e., our behaviors can create, not just reflect, preferences.

Maybe, until we understand more about CTE and can institute more precise preventive measures, we, the spectators, might decide that one of the choices: to ban football or to eschew watching – is more attractive than the other. And surely, full disclosure of the game's risks should be conveyed to all players. Then again, perhaps we should rethink allowing youngsters even to play the game. Some experts are making this case.

[1] For some traumatic injuries, damage is not necessarily related to intensity. Thus, for commotio cordis, a rare event that triggered the cardiac arrest of 24-year-old football player Damar Hamlin, the traumatic blow must be neither too strong nor too weak, and the precise locus of the attack is critical to inflict severe damage.

[2] “the chief risk factor for CTE… is characterized by misfolded tau protein that is unlike changes observed from aging, Alzheimer’s disease, or any other brain disease.” “The pathognomonic lesion of CTE consists of perivascular aggregates … in neurons … [deeply embedded[ at the depths of the cortical sulci. [These]… findings are inconsistent with a neuropathological diagnosis of AD in individuals with substantial RHI exposure and have both clinical and medico-legal implications.”

[3] Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) is the tearing of the brain's long connecting nerve fibers (axons) when the brain is injured as it shifts and rotates inside the bony skull. DAI usually causes coma and injury to many different parts of the brain. The primary goal of the SAVE study “is to determine how repeated head impacts from playing contact sports can lead to long-term thinking, memory and mood problems.”