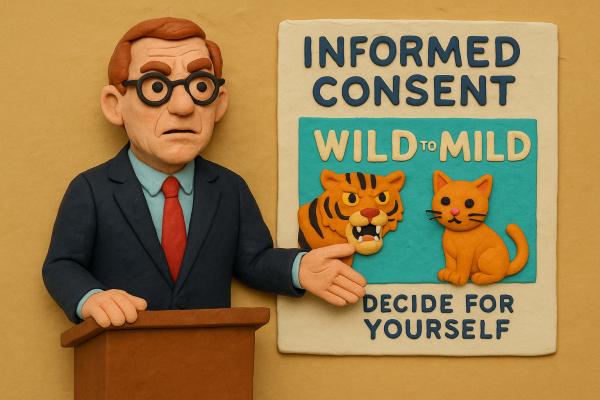

HHS Secretary Kennedy pulled the vaccination advertisement, wanting to promote, in the words of Stat, “the idea of ‘informed consent’ in vaccine decision-making instead.” The campaign was launched in 2023 and resumed this fall. According to the CDC website,

“The Wild to Mild campaign is based on consumer research showing that many people believe flu vaccination doesn't work because of first or second-hand experience where vaccination may not have prevented illness. Flu vaccine varies in how well it works. For many years, CDC measured vaccine effectiveness according to how well it prevented illness that required medical treatment. In recent years, however, CDC has expanded its vaccine effectiveness work to include looking at how well flu vaccine works at preventing serious outcomes, like emergency department visits and hospitalizations. This work has contributed to a strong and growing body of evidence that flu vaccination reduces the risk of serious outcomes in people who get vaccinated but still get sick. The Wild to Mild campaign visually shows how flu vaccination can tame flu illness from wild to mild by showing a wild animal, like a tiger, juxtaposed against a more domesticated animal or toy like a kitten. …The intent of the Wild to Mild campaign is to reset public expectations around what a flu vaccine can do in the event that it does not entirely prevent illness.”

As expected, pushback followed. Much of it, as my colleague Dr. Billauer pointed out, centered around the legal niceties of “informed consent.” Given that Secretary Kennedy is a lawyer by training, I suspect the next iteration of vaccine communications from the CDC will be “balanced,” identifying risks as well as benefits, fair and balanced, like Fox News, in the hopes of looking more legally bulletproof.

But here’s the thing: after more than three decades as a physician, I can tell you that neither Barbara’s nor Bobby’s legal hairsplitting has much to do with informed consent. That’s a legal fiction. Informed consent is a scripted dance that happens after a patient has already made up their mind.

What buying a car can teach us about consent

Before jumping into the medical nuances involved in “informed consent,” let’s start somewhere relatable with a more common example. Think about buying a car. Is “informed consent” that moment in the closing room when you’re handed a stack of forms, contracts, and state-mandated disclosures? Or is it that hour or more spent with a salesperson (and their “manager”), where you're pitched trim packages, payment plans, and “limited-time offers?”

Here is the ground truth, informing you of your benefits, risks, and options; the informed consent is not separate from the sales pitch; it is the sales pitch. Take it from me: I’ve been selling surgery for 30 years – because no one comes into the office and says, please operate on me. (If they do, there are other problems)

The sales pitch begins with understanding the customer’s (patient’s) needs and resources. Physicians learn this information from the history and physical examination (H&P), along with any ancillary tests that the H&P suggests. Because we use professional jargon, we refer to it as diagnostic testing. Based on that assessment, we offer an opinion on the therapeutic approach that is most beneficial. Because we are fiduciaries and required by professional obligation to act in your, rather than our, best interests, we will mention alternatives as well as any adverse consequences of your options.

But here’s where it gets interesting: how I frame those options matters a lot. How I present those alternatives and consequences, the context is critical in nudging you in one direction or another. Consider the classic question for those facing life-altering surgery, “What are my chances for success or complications?” What they really want to know is, “How safe and effective is this procedure in your hands, doctor?”

Often, I recite the best recollection of my experience, which is frequently the results we report to third parties, such as surgical or State registries. Physicians can answer with textbook numbers, the ones offered up by experts testifying in a courtroom. Should I give the patient a numeric value, say a 3% risk of dying, or offer a 97% chance of surviving, or an analogy saying it is comparable to open heart surgery. Every one of those is true, and each moves the patient’s decision in differing directions. The astute physician, like the successful auto salesperson, knows which of those identical bits of information will be best received. From the point of view of knowledge and experience, the physician holds most, if not all, of the cards.

Reframing the conversation

Secretary Kennedy’s reframing of health decisions around “do your own research” is the lawyerly belief that with your research in hand, you have leveled the playing field of knowledge between you and your physician. We like to believe that data alone will guide patients—or the public—to the “right” choice. But how that data is presented, who presents it, and when often matters more than the numbers themselves. Informed consent isn’t about paperwork; it’s about trust, framing, and context. Whether we're talking flu shots or fuel-efficient sedans, the real informed consent happens long before you sign anything. It’s the story you’re sold—and how well you believe it fits your and your family’s needs.