Perhaps you have seen the ads running on late night TV soliciting for patients to join a class action lawsuit against the manufacturers of a pelvic sling for women. What is that all about? A recent study and analysis in the British Medical Journal shed some light on a regulatory loophole for medical devices that may have resulted in harm. Some of the authors are plaintiff witnesses in device liability cases, including this one.

Clinical Background

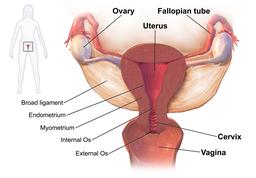

A weakness of the pelvic floor is common in women because of childbirth and pregnancy. As the pelvic muscle weaken or are damaged it results in difficulties with urination, defecation and a collapsing of the inner structures of the pelvis (like the uterus and intestines) into the vagina, called prolapse. It can be a debilitating condition and is treated with exercise to increase the strength of the pelvic floor and surgery to hoist the parts back into position. Transvaginal (placed through the vagina) mesh, is used as a sling to tack the uterus and bladder back up in their normal position. The device is made from a well-recognized ubiquitous biomaterial, polypropylene that has a long safety record as suture material. When polypropylene is used as a mesh, it differs in size and how the mesh is woven. Unlike the suture material form, polypropylene mesh may shrink after implantation, and this may lead to severe pain or erosion of the mesh into pelvic organs including the vagina. A Cochrane meta-analysis put a 10% rate on those occurrences. In some cases the mesh needs to be removed – not a smooth operation as the mesh is designed to incorporate into the tissue to increase the mesh’s support, making it far more difficult to remove.

Regulatory History

The FDA classifies medical devices as being a low, moderate or high risk. Those at high risk require clinical testing before approval, those with low risk need little if any testing. But devices of moderate risk, Class II, as vaginal mesh was initially categorized, live in a grey area involving the 501k process. For 501k Class II devices, there is no need for clinical studies as long as the manufacturer can demonstrate ‘substantial equivalence’ to already approved devices. Over time, if product B is almost equivalent to gold standard product A, then product C can be approved if it is nearly equivalent to newly approved Product B creating a chain of equivalence making it difficult to say how far “equivalence” has been stretched.

That is what occurred with vaginal mesh. The original material was a mesh of polyester used for hernia repairs, which was a “substantial equivalent” for a mesh made of polypropylene. In all, 61 devices were approved and on the market, the result of a chain leading back to only two “originating devices approved in 1985 and 1996.”

As an additional layer of protection, the FDA does require post-market surveillance of these Class II devices, studies of the safety and efficacy as they are used. But studies of implants take time, for vaginal mesh the median was five years after marketing approval (with a range of 1 to 14 years). With time, these studies along with almost 4,000 reports of serious complications from physicians or manufacturers, resulted in the FDA rethinking its approval of vaginal mesh and asking the manufacturers in 2012, to perform additional safety testing. 66% of the devices were then withdrawn from the market rather than undergo further testing. Ultimately the FDA reclassified vaginal mesh as a Class III device “requiring more stringent testing in trials before clearance.”

The authors argue for two sensible changes and remember they did disclose conflicts of interest regarding medical testimony and expert opinion on regulatory matters.

First, that implantable devices treated as ‘substantially equivalent” by the 501k process be initially treated with an investigational device exemption; which allows limited access to the product, initially in clinical trials with adequately long-term mandatory follow-up. Because the devices are implanted, and some issues do not surface early, they recommended a five year study period. These trials could provide real safety and efficacy information without exposing the general public.

Second, they recommend that all implantable devices be prospectively placed into long-term clinical registries, guaranteeing the collection of long-term data although who is responsible for data entry remains a problem. Despite some concerns about transvaginal mesh early in its use, a registry was only started 20 after initial marketing.

Source: Transvaginal mesh failure: lessons for regulation of implantable devices