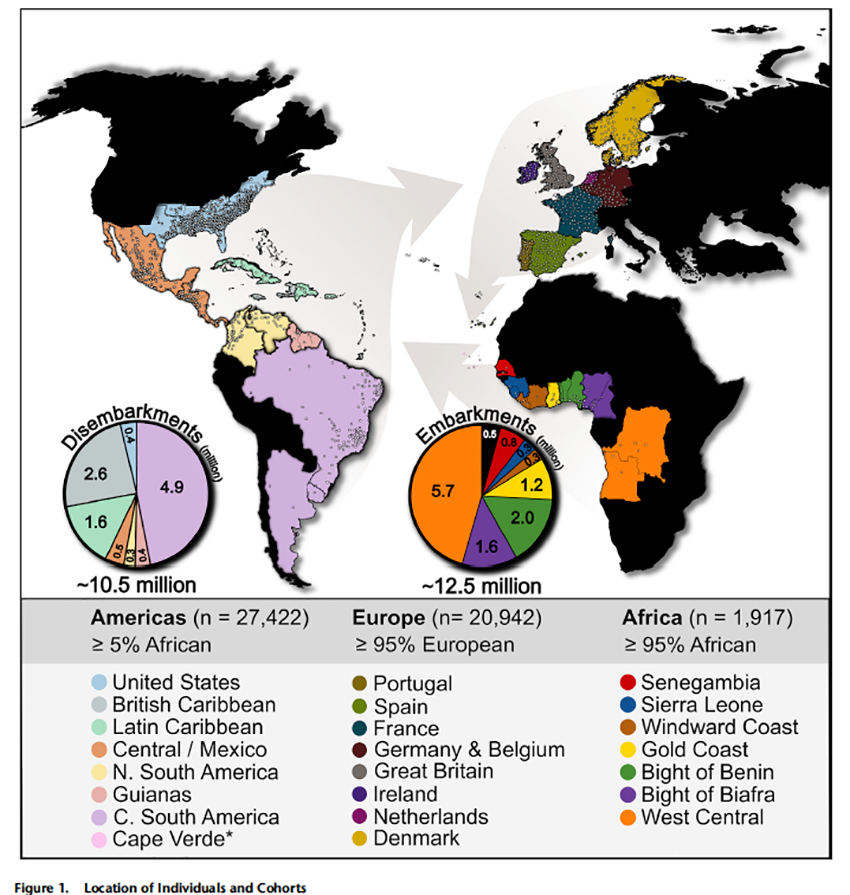

In a little over 350 years, 12.5 million Africans were forcibly moved into the Americas. Current events continue to ripple from that displacement as well as the more recent Great Migration of African-Americans from the South. 23andMe used its knowledge of genetic ancestry, combined with shipping records, to help us see into the Middle Passage in some new ways. Contemporaneous shipping manifests tell us that

- 10.1 million, primarily male, enslaved individuals were transported to the Caribbean, and Central and South America

- 500,000 more disembarked in North America

- 500,000 of these individuals were subsequently transported again, throughout the Americas

- The slaves comprised “48 distinct ethnolinguistic groups … targeted across Atlantic Africa,” often originating in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola, but with time coming from Nigeria, Cameroon, Benin, and Gabon.

23andMe used its genetic data set along with other global sets to construct cohorts of ancestry, reflecting hemispheric Americans, Atlantic Coast Africans, and Western Europeans. They excluded Americans with less than 5% African ancestry, and Africans, and Western Europeans with less than 95% of their ancestry. They used their methodology to identify “the ancestral origins of chromosomal segments in individuals using all available genotype data” – creating identity by descent, IBD. The dataset included about 50,000 individuals, which is small for genetic studies. What did they find and subsequently hypothesize?

The percentages of various IBDs and I will call them ethnicities, were proportional between embarkation records and those found in the Americas, in aggregate. But the current distribution was not as concordant. For example, fewer individuals with ethnicity from Senegambia were found in the US and northern South America than had disembarked.

93% of African Americans can trace their ancestry back to four regions in Atlantic Africa [1], primarily Nigeria, while nearly half of “Mexican and Central American individuals have only Senegambian ancestry.”

In comparing the relative contribution of male and female genetics, they found an “African female bias” throughout the Americas, coupled with a “European male sex bias” everywhere but in the Latin Caribbean and Central America.

Based on those genetic findings, the authors reach the following conclusions.

- That slavery shipping manifests are consistent with the current IBDs in the Americas when aggregated.

- Disparities in ethnic proportions between those disembarked and those now present appear to have historical roots. For example, as the transatlantic slave transport slowed, more slaves were transferred from the British Caribbean to the American colonies and Latin America.

- Individuals from Senegambia are under-represented. The researchers felt two different factors could account for this. First, that the slave trade began in Senegambia, resulting in more slaves earlier in the slave trade’s time course, resulting in more genetic mixing and an undercounting of genetics. Second, that slaves from Senegambia had more significant mortality. Both in their Middle Passage because it involved more children. And because their expertise as cultivators of rice found them enslaved in areas with malaria and other life-threatening conditions.

- In what is perhaps the most horrifying conclusion, the researchers reference the known rape and sexual exploitation of female slaves. While in North America, African women contributed 1.5 to twice as much DNA to the genetic pool as African men, in Latin America, the contribution by African women rose to between 4 and 17-fold higher than African men. They attribute this significant difference to both a higher mortality for enslaved males as well as “a common practice called branqueamento, or racial whitening… National branqueamento policies were implemented in multiple Latin American countries, funding and subsidizing European immigrant travels with the intention to dilute African ancestry through reproduction with light-skinned Europeans.”

There are several worthwhile take-home messages in the study — first, racial categories based upon phenotype blur genetic differences. If we are to truly practice “precision,” personalized medicine, we need to think of race much differently. Second, genetics and culture interact influencing one another. As the researchers write,

“…overrepresentation of Nigerian ancestry in parts of the Americas is explained by the intra- American trade of enslaved people from the British Caribbean, and underrepresentation of Senegambian ancestry across the Americas is supported by accounts of early trading and high mortality from this region. Patterns of variation across the Americas, such as lower African ancestry and a higher African female sex bias can be attributed to socioeconomic factors, non-African male admixture, and inhumane treatment of enslaved people.”

[1] Nigerian (Nigeria), Senegambian (Gambia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Senegal), Coastal West African (Sierra Leone, Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire, Liberia), and Congolese (Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo)

Source: Genetic Consequences of the Transatlantic Slave Trade in the Americas, The American Journal of Human Genetics DOI:10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.06.012