"I'm going to lose the script, and I'm going to reflect on the recurring feeling I have of impending doom. We have so much to look forward to so much promise and potential of where we are, and so much reason for hope. But right now. I'm scared."

Those are the recent words of CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky. Much of the messaging to the public during the pandemic has used fear of the consequences to ourselves, families, or society as a “cudgel” to strongly influence our behavior. A new study looks to see if fear is the best motivator.

A Bit of Theory

There is a hypothesis, the protection motivation theory, that holds that our motivation to “comply with risk-relevant recommendations” is based upon our perceived threat to ourselves and our ability to comply with the recommended actions – our self-efficacy. The cell-phone data on Florida’s seniors who had them drastically limited their movement weeks before a government mandate is sufficient proof of the idea. Prior studies on other forms of threat suggest that self-efficacy, that capability of responding, may more strongly correlate with compliance than fear. The current study sought to tease out the relationship between the two in the current pandemic. Trust in one another, to follow similar norms of behavior, and trust in institutions to be willing to enforce those norms was also assessed.

The Study

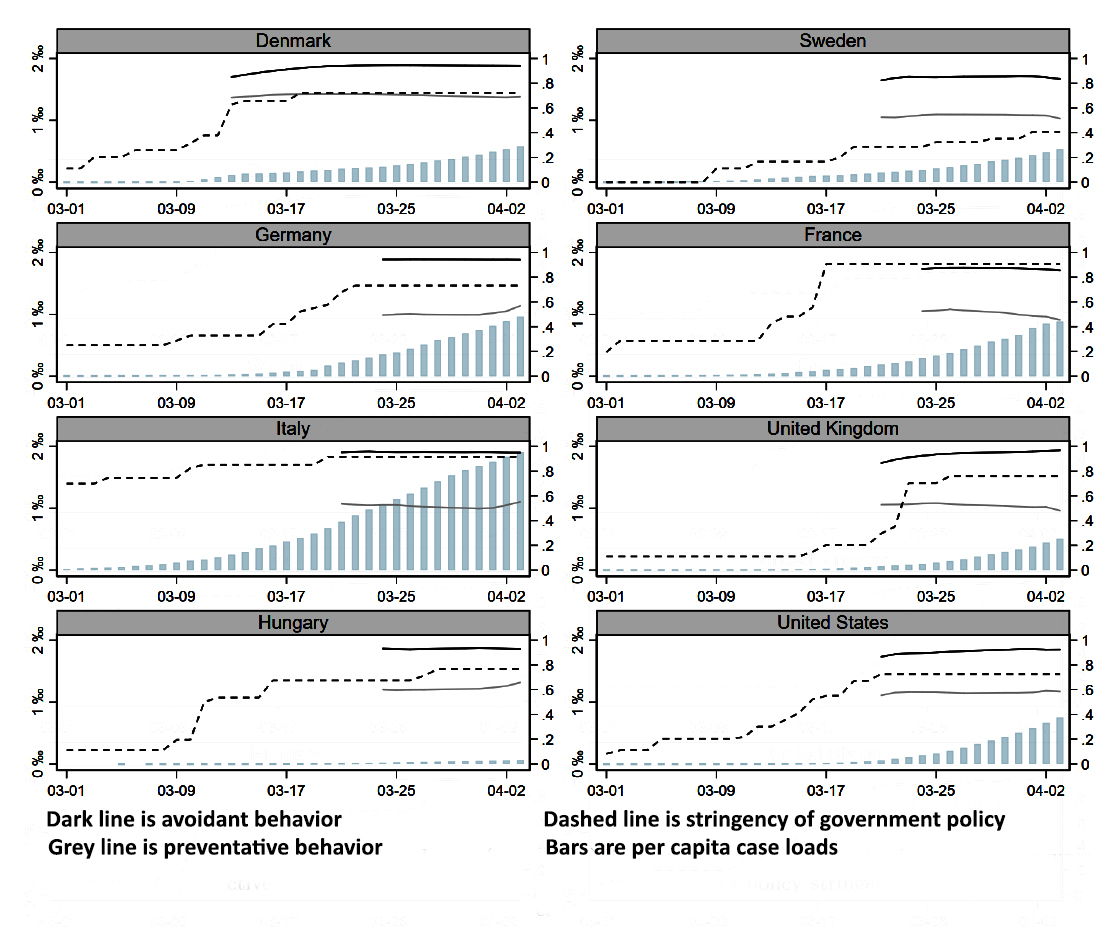

Researchers made use of an online survey tool during the initial wave of the pandemic, roughly mid-March to early April 2020. The 26,500 participants came from eight countries [1], and the sample was restricted to match the age, gender, and geography within these countries. In addition to the usual demographics, the researchers assess avoidant behavior, e.g., social distancing and masks, preventative behavior, e.g., hand washing creating scales where higher values reflected increasing avoidance or prevention. Fear was based on the participant's level of concern towards themselves, family, and friends – again, higher values reflected greater fear.

Self-efficacy requires both knowledge of what to do and a feeling that you are capable of those actions. Self-efficacy was scaled based on measures of participants knowledge, i.e., “To what degree do you feel that you know enough about . . .” how to avoid being infected, the symptoms, what you should do if you become ill, etc. And how agreeable the participant was with the statement, “I’m certain I can follow official advice to ‘distance myself’ from others if I want to.”

The Results

The aggregated data graph above shows that independent of both the cases and the stringency of government policy, there was strong avoidant and preventative behavior. However, avoidance, e.g., social distancing, was more robust than preventive measures. This difference rings true in other health situations, specifically the less frequent routine hand-washing by physicians between patients.

The aggregated data graph above shows that independent of both the cases and the stringency of government policy, there was strong avoidant and preventative behavior. However, avoidance, e.g., social distancing, was more robust than preventive measures. This difference rings true in other health situations, specifically the less frequent routine hand-washing by physicians between patients.

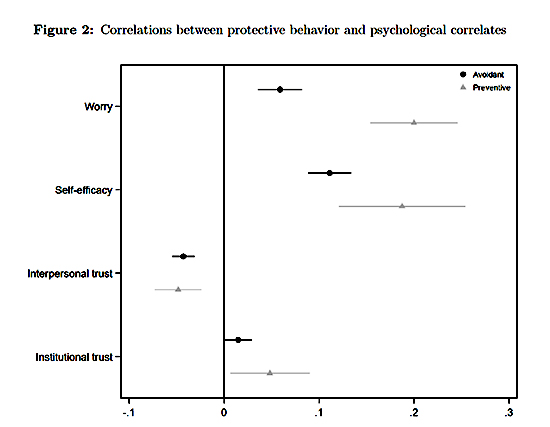

Increasing worry and self-efficacy both increased compliance with avoidance and preventative behaviors. But self-efficacy’s effect was more substantial. Institutional trust has a similar but much smaller effect. Increasing trust of individuals reduced preventive behaviors. After all, you trust them to be doing “the right thing” – defined by what you perceive is right. And these results held for all the countries, differing cultures were not a salient concern.

The researchers also looked at how these four factors interaction. There was “strong evidence” that an individual’s increasing self-efficacy decreased the role of fear as a predictor of protective behavior – fear is not the only, let alone most effective tool in healthcare communications. Belief in your ability to “control your fate,” self-efficacy, is potentially a much better means to move our behavior in the necessary direction.

Take-aways

“To facilitate society-wide protective behavior during a massive crisis such as the first wave of COVID-19pandemic, the establishment of a strong sense of self-efficacy is key.”

The researchers point out that the continuing drum-beats of fear take a mental toll and often lowers the threshold to enact “undemocratic” treatment of some groups – both increasing concerns in our approach to COVID-19.

“While trust may increase other forms of protective behavior, the trusting mindset seems to make it psychologically difficult to treat others as infection threats.”

Greater trust between individuals reduces protective behavior though whether this reflects our desire to “fit in” or mimicry of our tribe remains unknown. That said, it does help explain our pandemic pods.

Fear may motivate quickly, but its effect can linger long after the need for an acutely heightened concern has faded. Equipping the populace with the tools to safely navigate a pandemic may get the exact behavioral change without the behavioral hangover.

[1] Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Sweden, the United Kingdom (UK), and the United States.

Source: Compliance Without Fear: Individual-Level Protective Behavior During the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic British Journal of Health Psychology DOI:10.1111/bjhp.12519