The average American uses ten personal care products daily, and although the type of products has changed during the pandemic, their use has not. Sales of eye makeup soared, and lipstick declined, as masks hid most of our face and video conferencing exploded. Lipstick and skincare sales are rising as mask use becomes more optional and meetings are more often held in person.

Background

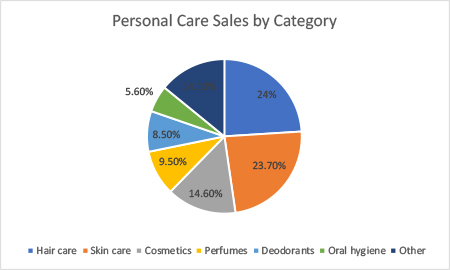

The chart shows sales of personal care products by category in the US in 2020.

It is evident that both men and women use these products on every inch of their body

- deodorants under arms

- skincare products all over the skin

- shaving products on the face and legs

- shampoos on the hair

- nail polish on fingers and toes

- lipstick and lip balm

With so much use, it is understandable that there is concern about the exposure to hazardous chemicals by using them. One of the biggest trends is “clean beauty,” including “natural” products that do not contain harsh chemicals.

Are concerns over hazardous chemicals in cosmetics warranted? How well does the FDA protect us?

Cosmetics are Considered Low-Risk

“All substances are poisons; there is none which is not a poison. The right dose differentiates poison from a remedy.” Paracelsus

This classic quotation remains the basis of modern toxicology and underscores why cosmetics are generally considered low-risk to consumers.

Dose involves:

- The amount of the substance in the cosmetic

- The substance's ability to cause harm, based on the amount absorbed and distributed to target organs in the body.

Most cosmetics consist of a mixture of many substances, so any one chemical of concern would tend to be present at low levels. The ability of these chemicals to cause harm is further limited by application to our skin, whose natural role is to defend against foreign materials. Skin presents a much more effective barrier to chemicals entering the bloodstream than eating, drinking, or inhaling them.

Because chemicals are present in very low levels and exposure is usually through the skin, cosmetics have generally been considered low-risk by regulatory and public health agencies.

What are cosmetics?

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) is the most important regulation on cosmetics in the US It is a very old regulation (passed in 1938), and under this law, cosmetics are defined more broadly than as “beautification” products; they are defined according to their intended use:

“Articles intended to be rubbed, poured, sprinkled, or sprayed on, introduced into, or otherwise applied to the human body…. for cleansing, beautifying, promoting attractiveness, or altering the appearance.”

Substances intended for therapeutic use, such as treating or preventing disease, are drugs and do not fall under the auspices of the FD&C Act; instead, they are regulated under the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

But a substance can be both a cosmetic and a drug – when it has two intended uses. One example is antidandruff shampoo: it is a cosmetic because its intended use is to clean hair, and a drug because it is also intended to treat dandruff. A deodorant is a cosmetic; a deodorant with antiperspirant is both; sunscreen is a drug; with a moisturizer, it is also a cosmetic. These substances must follow the regulations for both cosmetics and drugs.

Finally, in an odd twist, soaps are not considered a cosmetic, even though they meet the definition of use for cleansing. If an article meets the FDA’s definition of soap [2], it is regulated by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC).

How are Cosmetics Regulated?

The FD&C Act prohibits the marketing of

- adulterated products- containing a poisonous, filthy, or deleterious substance, one packed under unsanitary conditions, or containing a color additive that has not been determined to be safe by the FDA except for coal-tar based hair dyes. [3]

- misbranded products – with false or misleading labeling

The FDA explicitly prohibits ten substances, including mercury, vinyl chloride, and methylene chloride, from use in cosmetics.

Cosmetics (unlike drugs and medical devices) do not require FDA approval before they can be sold in the US (except for color additives). The company’s manufacturing cosmetics have a legal responsibility to ensure the safety of their product but are not required to carry out specific tests on the cosmetics, nor share that safety information with the FDA.

Consumer Cosmetic Safety Programs

Since the FDA doesn’t test cosmetics before they go on the market, review boards, funded by industry trade associations, have been established to assess the safety of ingredients in cosmetics. While funded by industry, the reviews are carried out by independent scientists without industry ties to ensure the scientific integrity of the studies.

In the US, the largest is the Expert Panel for Cosmetic Ingredient Safety, funded by the Personal Care Products Council. The board consists of nine voting board members, mainly medical professionals and scientists, and three nonvoting liaisons representing government, consumers, and industry. They review scientific studies on ingredients in cosmetic products and publish their results in peer-reviewed journals. At a forum open to the public, they vote on whether to consider cosmetic ingredients as safe, unsafe, or insufficient information.

- As of 2017, they had reviewed over 4,740 cosmetic ingredients

- 4,611 were determined to be safe, 12 unsafe, and 117 had insufficient information to assess safety.

The Environmental Working Group (EWG)

As discussed by Dr. Josh Bloom, the EWG has a cosmetics database that rates the safety of 10,500 personal care products. Their 10-point (low to high concern) ratings are based on comparing the ingredients in cosmetics to listings in 60 toxicity and regulatory databases. Here are the critical problems with the cosmetic database:

- Their methodology does NOT consider the dose of the ingredient – either the amount in the cosmetic or its ability to cause harm. Dose is the most important consideration when evaluating the safety of cosmetics.

- Many of those databases are simply lists of chemicals, never intended as checklists to evaluate toxicity.

- Most of the databases are 15 to 27 years old and out of date. Science changes, using out-of-date databases will result in out-of-date conclusions.

What about Europe?

Europe, like the US, does not require regulatory approval before selling cosmetics. But Europe:

- Has a more extensive list of banned substances, over 1400 ingredients (compared to 10 in the US), but over 80% of these have not been used and never would be used in cosmetics, e.g., jet fuel, pesticides, antibiotics, arsenic, cyanide, and rat poison. Europe’s list of banned substances combines substances banned in cosmetics, food, and ingredients not connected to cosmetics.

- Europe requires each manufacturer submit a “safety assessment” on each cosmetic. These safety assessments are a boon to consulting toxicologists; I have worked on many of these over my career but are basically filed away with all the other paperwork, adding cost and time to the end product. In my opinion, they don’t actually contribute to safer cosmetics

What to do

For some, the initial impulse may be to add more regulations to address the safety of our cosmetics. However, is this a productive approach? The FDA can be exceedingly slow to take action, even during a pandemic! Scientists have known for decades that lead presents a health risk, even at very low levels. Would it surprise you to find that the FDA did not repeal the approval of lead acetate as a color additive in hair dyes until 2018?

The one issue I believe needs special consideration is imported cosmetics. The US and Europe have similar regulatory frameworks, but countries such as China have no regulatory requirements. Imports to the US are required to conform to the FD&C Act and not be adulterated or misbranded. The US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) can inspect and seize foreign cosmetics [4], but seizures underscore why other countries must adopt a regulatory framework similar to the US or Europe. In addition, our labeling laws do not require disclosure of cosmetics manufactured in foreign countries, (as long as they are labeled with a US distributor’s address), where manufacturing conditions may have little to no government oversight.

I believe that the current public-private partnership can and does work well. Although the Expert Panel for Cosmetic Ingredient Safety results carry no regulatory authority, not everything needs to be regulated. It is in manufacturers’ self-interest, both legally and publicly, to not use ingredients that have not been approved for use the Panel.

[1] This article will use the term “cosmetics” as defined by the FDA. The FDA’s definition of cosmetics is much closer to “personal care products” and includes many products used by men and women.

[2] The bulk of the nonvolatile matter in the product consists of an alkali salt of fatty acids. The product’s detergent properties are due to the alkali-fatty acid compounds, and is labeled, sold, and represented solely as soap.

[3] Coal-tar hair dyes are hair coloring products that were originally by-products of the coal industry but are made primarily from petroleum today. In 1938, due to lobbying by the hair color industry, the FDA exempted them from the provision of the FD&C requiring them to be approved safe. More recently, the FDA has required that these products contain warning labels acknowledging the potential for allergic reactions.

[4] They have recently seized false eyelashes, makeup, and cosmetic contact lenses.