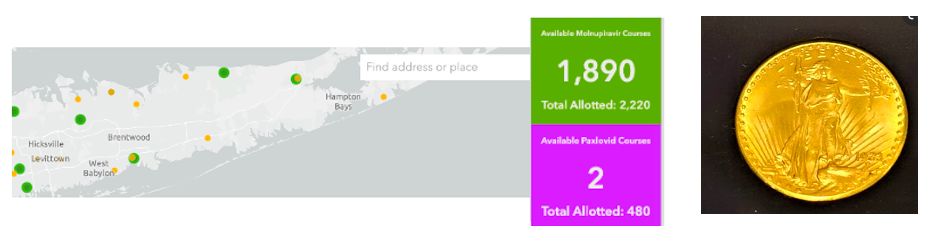

About two months ago, when Pfizer's Paxlovid (1) was first distributed to a very select group of pharmacies throughout the US, you pretty much had to know the Pope (and perhaps his pharmacist) to get your hands the drug. As I wrote in early February, you had about as much of a chance of finding a $20 gold piece on the sidewalk as locating a pharmacy that had the stuff in stock.

(Left) January 17th, the availability of molnupiravir (1,890 courses) and Paxlovid (zero courses - the 2 isn't real) on Long Island, NY, Population 8 million. Ignore the yellow dots; they represent antibody treatments. Each dot represents a pharmacy that has been allocated antiviral drugs. (Right) A 1923 St. Gaudens $20 gold coin, currently worth about $2,200. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

The numbers above came from an HHS website, COVID Therapeutics Locator, which showed the number of courses allotted and how many remained in a given area. The site also cautioned the public that this information was for use by physicians, not patients. Of course, that didn't stop terrified people (Omicron was in full swing at the time) from obsessively calling multiple pharmacies to see if they had any of the product. Pharmacists I spoke to sounded like they had battle fatigue from answering the same question all day long.

By early February, drug supply had become less of an issue. Both Paxlovid and molnupiravir were available, at least in the Long Island area.

What about nationwide?

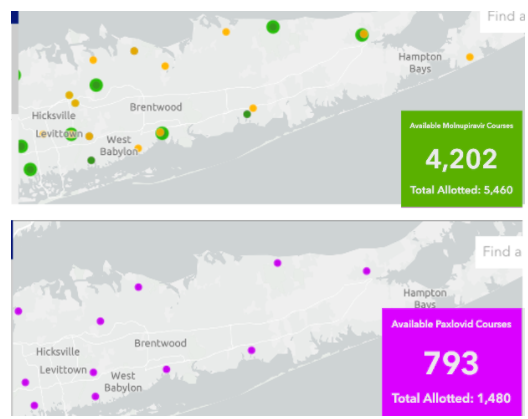

A recent NPR article revealed that COVID drugs are sitting on pharmacy shelves and in refrigerators (2) unwanted and unused, even though 2,000 people per day are still being hospitalized with COVID (as of early March).

Source: US Department of Health and Human Services (as of March 13). Credit: Tien Le/NPR

The chart above, courtesy of NPR, above contains data for both two antiviral pills Paxlovid and molnupiravir, as well as two antibodies (Sotrovimab, Bebtelovimab) and Evusheld (a combination of two long-acting antibodies, tixagevimab and cilgavima). (3)

What is going on?

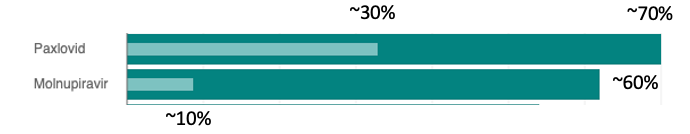

Let's focus on the two oral antivirals, Paxlovid and molnupiravir (4).

As the incidence of Omicron (at least the original subvariant) has fallen drastically in the US, and people are casting off their masks, COVID is much less scary, at least for now. COVID has fallen off the front page. In the absence of continuous horror stories on the nightly news, who needs drugs? When/if this changes, courtesy of a new evil variant that may be silently "brewing" while we look ahead to a healthy spring, the drugs may become quite popular once again.

Both drugs have some baggage.

Paxlovid, although enormously effective in preventing hospitalization and death, has some baggage – a lengthy list of drugs that it interacts with. While much of this problem can be minimized by stopping a drug (like a statin) during the five-day course of Paxlovid, some medications, especially blood thinners and antiarrhythmics, cannot necessarily be stopped safely, even for a short time.

This has caused a difference in opinion, albeit a friendly one, within the ACSH family. I recently wrote in support of an easy access program like "test to treat," which was recently proposed by the Biden administration. The program would permit pharmacists to dispense Paxlovid – without a physician's prescription – to someone who tests positive, enabling them to have instant access to the drug when it will do the most good. If there is a deadly new surge caused by another variant (or subvariant of Omicron), easy and rapid access to Paxlovid will save lives and prevent people from needing to be hospitalized.

But ACSH friend, advisor, and my personal friend, Dr. Henry Miller, has argued that Paxlovid should be administered more carefully (and only with a prescription and input from a physician or PA) because the drug-drug interactions can be dangerous. His piece in the Wall Street Journal makes this quite clear.

We both have valid points. Molnupiravir has its own baggage, two pieces, in fact. In some assays, molnupiravir has been found to be mutagenic, so its use in pregnant and breastfeeding women is discouraged. Perhaps worse, molnupiravir is far less effective than Paxlovid – about 30% vs.>90% in preventing hospitalization and death. This probably explains why molnupiravir is barely being used.

Who's right? Neither of us. Neither drug is perfect. Dr. Miller is more concerned with Paxlovid's drug-drug interactions, and I'm more concerned about molnupiravir's modest efficacy. We have different points of view, which is a function of certain flaws in each drug.

The US public has a short attention span. Two months ago, people terrified of Omicron were undertaking daily espionage missions trying to outsmart others to get the last package of Paxlovid while now no one cares. Based on the relentless history of COVID generating one more infectious variant after another, I seriously doubt we've seen the last of what this virus has to offer. Should new variants develop that are not covered by vaccines, our current oversupply of COVID drugs will be a good problem to have.

NOTES:

(1) Paxlovid is a two-pill combination consisting of an antiviral medication nirmatrelvir and ritonavir, which extends the half-life of nirmatrelvir in the blood.

(2) Biologics, like antibodies and vaccines, must be kept cold and have a limited storage time, after which they must be discarded. Pills are far more stable and can often remain intact for many years.

(3) Evusheld is a combination of two long-acting monoclonal antibodies. It's not a vaccine but is used prophylactically.

(4) I am focusing only on the antiviral pills because the utility of the antibodies can drop off quickly, depending on the variant. The antiviral drugs treat all variants; their utility is not impacted by mutations in the spike protein.