The world of chemical scares is a bit like a perpetual horse race, usually with the same tired old horses –various chemicals – in the same race. Today, featured in the 5th race at Oncology Downs in New Jersey is Packet of Cancer – a four-year-old thoroughbred filly that was the prohibitive favorite at 3-5. The horse, which was a 3-1 underdog only last week, has attracted some serious wagering following the publication of a paper in PLOS Medicine about the association of two artificial sweeteners with cancer. The filly came flying out of the gate never looking back, and won by seven lengths.

Here we go again. Yet one more study in a seemingly infinite collection of them, all about the harms of sugar substitutes. This time, Charlotte Debras and colleagues at Sorbonne Paris Nord University joined the race with "Artificial sweeteners and cancer risk: Results from the NutriNet-Santé population-based cohort study," which claims to support the long-held belief that artificial sweeteners are bad news. The usual – you should start digging your grave while sipping a Diet Coke because it ain't gonna be long before you'll be in it.

Does this horse have legs? Let's look. Warning: Before you try to read a very long, detailed exercise in stamina, I'm going to do you a favor. Much of the paper is about the study methodology, statistical analysis, and the attempt to correct for a bazillion variables in the populations studied. Feel free to read the thing (three of us did and our heads exploded), but it's not necessary. The paper is mostly noise and its real message (or lack thereof) can be seen by focusing on some of the data from which the authors draw their conclusion.

The Study

More than 100,000 French adults were followed over a 12-year period during which time this happened:

"Participants declare all foods and beverages consumed during main meals and other eating occasions, and they provide information on portion sizes via validated photographs or standard serving containers. Baseline dietary intakes were evaluated by averaging all 24-hour dietary records provided during the first 2 years of follow-up (up to 15 records). Daily intakes of energy, alcohol, and macro- and micronutrients were assessed via the NutriNet-Santé food composition table (providing nutritional composition for about 3,500 items) Nutrient intakes from composite dishes were estimated according to usual French recipes as defined by nutrition professionals. Dietary energy under-reporters were identified using basal metabolic rate and the Goldberg cut-off method, and excluded from the analyses."

Let's just ignore the complicated protocol and focus on the findings because if the findings are invalid or inconclusive then the methodology is irrelevant.

Baseline Measurements

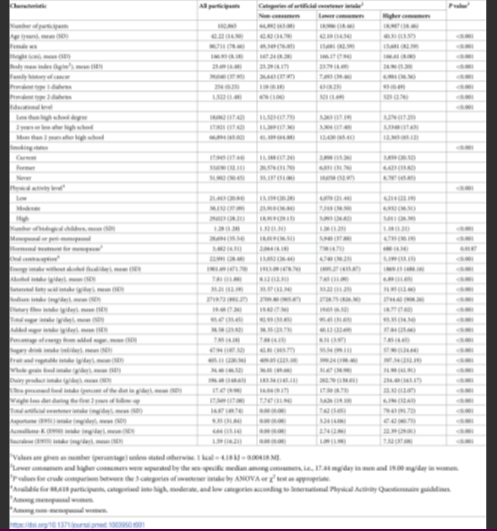

To compare the effects between groups, the characteristics of the participants prior to the study must be determined in advance. This is done (in excruciating detail) in the paper's Table 1: "Baseline characteristics of the study population, NutriNet-Santé cohort, France, 2009–2021 (n = 102,865)." The table is large enough to serve dinner for 100.

So, let's expand a few sections; there are some questionable (to put it nicely) data in there.

The group was divided (according to self-reported data) into groups of people who do not use artificial substitutes (Non-consumers, yellow, control group), and those who use only a little (Lower-consumers, green) and a lot (Higher-consumers, red).

Right off the bat, the baseline difference in BMI is intriguing. Compared to non-consumers (blue box), high-consumers (red box) had a BMI that was 7.2% higher – a small but significant number, especially when we see the magnitude of the changes in cancer rates later on. Since obesity is a known factor in the development of cancer, it is reasonable to ask whether any, perhaps all, of the measured effects in the study populations are simply a factor of the difference in BMI at baseline. Is this difference sufficient to invalidate the entire study? Hard to say.

Right off the bat, the baseline difference in BMI is intriguing. Compared to non-consumers (blue box), high-consumers (red box) had a BMI that was 7.2% higher – a small but significant number, especially when we see the magnitude of the changes in cancer rates later on. Since obesity is a known factor in the development of cancer, it is reasonable to ask whether any, perhaps all, of the measured effects in the study populations are simply a factor of the difference in BMI at baseline. Is this difference sufficient to invalidate the entire study? Hard to say.

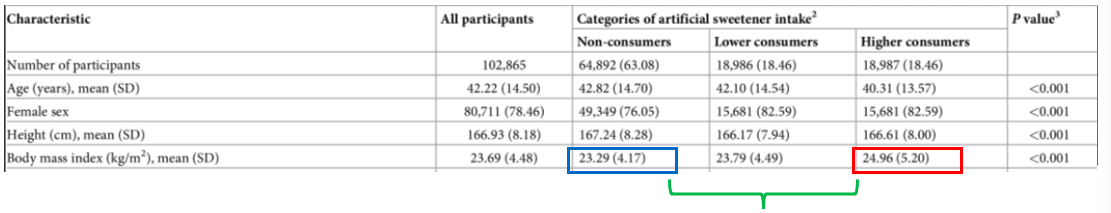

Then there's this: a look at the difference between the amount of sweetener used by the low and high consumers. It's quite a bit.

Low-consumers (green circle) used 7.6 mg of all sweeteners per day. High-consumers (red circle) used more than 10-times that. The trends for aspartame (15X) and acesulfame-K (10X) are similar. When you see (below) the very small difference in cancer rates between these groups it is not unreasonable to ask: if artificial sweeteners indeed cause cancer, why was there a minuscule difference in the cancer rate when the difference in the amount consumed sweeteners was huge?

Low-consumers (green circle) used 7.6 mg of all sweeteners per day. High-consumers (red circle) used more than 10-times that. The trends for aspartame (15X) and acesulfame-K (10X) are similar. When you see (below) the very small difference in cancer rates between these groups it is not unreasonable to ask: if artificial sweeteners indeed cause cancer, why was there a minuscule difference in the cancer rate when the difference in the amount consumed sweeteners was huge?

RESULTS

Bullsweet Cancer Claim #1 - All Cancer Incidence and Total Artificial Sweeteners

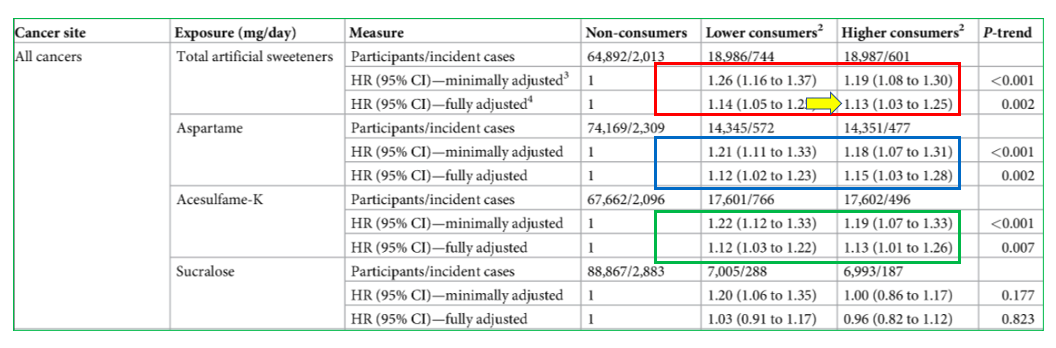

"In this large cohort of 102,865 French adults, artificial sweeteners (especially aspartame and acesulfame-K) were associated with increased overall cancer risk (hazard ratio [HR] for higher consumers compared to non-consumers = 1.13 [95% CI 1.03 to 1.25], P-trend = 0.002)."

It is here that you may conclude that we are looking at "Le Trash paper." (Table 2). The table takes up an entire page, so I have again carved out the relevant sections.

As you can see, there is little or no difference in the rate of all cancers in the total artificial sweetener group (red box), aspartame group (blue box), or acesulfame-K group (green box) (1). Yet, the authors claim otherwise. Note that the claim of an increased number of cancers (HR 1.13, 13%) is based on a single number in the entire chart, indicated by the yellow arrow. It's not only a single number but also a very small one.

Let's look at a few problems. First, note that in the minimally adjusted data (see below), higher consumers actually have a lower chance of cancer than lower consumers (HR 1.19 for the high, 1.26 for the low). This is overlooked; instead, the 1.13 figure is used. This becomes even more puzzling when you consider that in the same column, the lower consumers have a higher, albeit likewise insignificant risk – HR 1.14, 14%. It is obvious that these numbers are all the same.

Bullsweet Cancer Claim #2

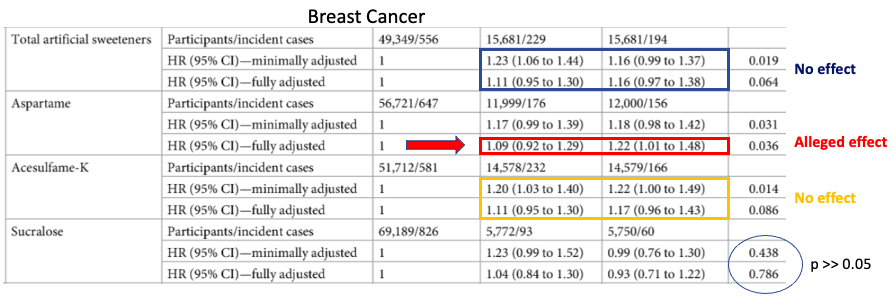

"More specifically, aspartame intake was associated with increased breast (HR = 1.22 [95% CI 1.01 to 1.48], P = 0.036)"

Again, let's look at the data.

The authors have again singled out one data point (red box/arrow) from the entire chart and managed to find something statistically significant: an association between breast cancer aspartame when the non-consumer group is compared to the high-consumer group. Even so, the HR is quite low – 1.22 – a tiny effect, and it only shows up only when the statistics were fully adjusted.

The authors have again singled out one data point (red box/arrow) from the entire chart and managed to find something statistically significant: an association between breast cancer aspartame when the non-consumer group is compared to the high-consumer group. Even so, the HR is quite low – 1.22 – a tiny effect, and it only shows up only when the statistics were fully adjusted.

Contradicting this trend is the data on acesulfame-K and total artificial sweetener consumption. The incidence of cancer is unaffected by total consumption of artificial sweeteners as a whole; acesulfame-K (if these numbers are to be taken seriously) seems to be protective against breast cancer, since the high consumers are slightly less likely to develop breast cancer in both the minimally adjusted and fully adjusted groups. Do you believe any of this?

What are the adjustments?

I have ignored everything relating to data adjustment. This is because of the parameters that were used to make them:

Adjusted for age (time-scale), sex (except for breast and prostate), BMI, height, weight gain during follow-up, physical activity, smoking status, number of smoked cigarettes in pack-years, educational level, number of 24h dietary records, family history of cancer, prevalent diabetes, energy intake without alcohol, alcohol, sodium, saturated fatty acids, fibre, sugar, fruit and vegetable, whole-grain foods, dairy products. All models were mutually adjusted for artificial sweetener intake other than the one studied. Breast cancer models were also adjusted for age at menarche, age at first child, number of biological children, baseline menopausal status, oral contraceptive use at baseline and during follow-up, and hormonal treatment for menopause at baseline and during follow-up.

There are more than a dozen parameters that were somehow factored in to make the data more reliable. Or were they? It is quite common for authors of data dredging papers to pick and choose which factors are included in order to crunch the numbers to find anything statistically significant. Why these variables? Are there other variables that, if included, would tip the tenuous balance in the other direction? Who knows?

It's certainly been done before. Crappy epidemiology papers can be made to give just about any result you want simply by choosing or omitting certain groups and applying one set of corrections instead of another. Did the Debras group play this same game? I have no idea. All I can say (to be kind) is that the evidence for the link between artificial sweeteners and cancers in this study is shaky, at best.

And a Note From a Chemist

There is a fundamental problem with the entire premise of the study – that artificial sweeteners are a single entity. All that aspartame, acesulfame-K, and surculose have in common is that they are perceived as sweet by receptors on the tongue. Aside from that, they are just three entirely different chemicals with different physical, chemical, and biological properties. So, any study that compares the carcinogenicity of aspartame with sucralose is automatically flawed. There is no biological plausibility for sweetness, real or artificial, being in any way connected to cancer.

More on the way

Stay tuned. Next month I will be covering the Endocrine Disruptor Sweepstakes at BPA Arena in Akron. At this time, Tiny Testicles is a solid favorite at 3-2, but don't overlook Anogenital Distance (4-1) from Phthalate Farms in Kentucky. He's been awesome down the stretch lately.

NOTE:

(1) Sucralose was left out of all the analyses because its use (or lack thereof) did not produce results that were statistically significant. It's harmless too.