Some quick background

For those not up to date, I recommend reading what I wrote a year ago. For those with less time on their hands, here are the key points

- Big Tobacco feels “there is no clear scientific evidence to support a federal menthol and flavor ban.”

- The Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee “found convincing evidence that menthol cigarettes’ availability increases the number of smokers by increasing the rate of smoking initiation and reducing the rate of cessation, particularly among black Americans.”

- Through several proposed mechanisms, Menthol does increase the addictive nature of nicotine, explaining “why 90% of tobacco products contain some menthol, labeled or not.” [2]

- Blacks smoked far more mentholated cigarettes than Whites, and more adolescents smoke mentholated cigarettes than adults across all ethnic groups. [3]

These facts suggest that mentholated cigarettes are both a bit of a gateway initiation into smoking cigarettes and are disproportionately used in the Black community.

A new day, a new study

The focus here was the success or lack thereof in quitting mentholated cigarettes and what, if anything, was used as a substitute. Prior studies of this group indicated some would go to the grey market to purchase “banned” cigarettes, others would quit, and others would vape or switch to non-mentholated cigarettes.

The data set was a survey, Southern Community Cohort Study, involving African Americans and Whites living in southern states and, for the most part, a low-income, low-education population. By intent, it sought to recruit a higher percentage of African Americans “to remedy under-representation” in prior large epidemiologic studies. Participants were initially interviewed and then resurveyed twice more during 2008 to 2015—those who self-identified as smokers were asked about their preference for menthol cigarettes. An initial cohort of 16,425 current or quit smokers was whittled down to 6,599 participants that completed all of the surveys.

Breaking up is hard to do

- Quit rates were essentially the same for menthol and non-menthol smokers, 4.4%

- Quitting smoking was associated with increasing age, household income, college education, and female gender; those who chose to continue smoking increased with increasing pack years.

- There was no statistically significant difference in quit rates when comparing gender, race, and use of menthol cigarettes.

- While the resumption of smoking was slightly higher among the mentholated (8.4% vs. 7.1%) when adjusted, resumption rates were not significantly different when stratified by gender, race, and use of menthol cigarettes.

- Those who resumed smoking often tried again to quit, but there was no significant difference in those smoking menthol or non-menthol cigarettes.

Connecting the data dots, bending the curve

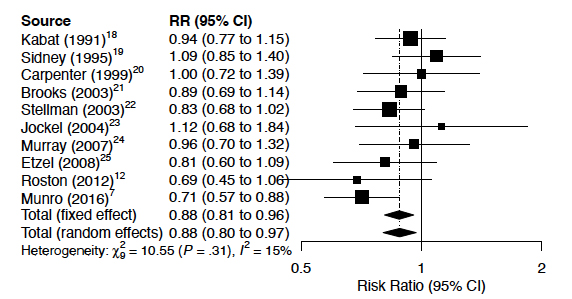

The researchers then considered the literature on the risk of developing lung cancer based on mentholated or not. Many studies suggested no difference, but the meta-analysis suggested that “a significantly lower risk of lung cancer is seen among menthol smokers” – a 12% reduction.

The researchers then considered the literature on the risk of developing lung cancer based on mentholated or not. Many studies suggested no difference, but the meta-analysis suggested that “a significantly lower risk of lung cancer is seen among menthol smokers” – a 12% reduction.

Despite their findings that there was no higher rate of resumption of smoking between menthol and non-menthol smokers, they go on to say

“There was, however, a suggestion of higher smoking resumption rates for those who quit menthols, particularly for African American participants.” [emphasis added]

“…our findings raise the unexpected hypothesis that menthol bans could result in a net long-term increase in cancer risk.”

Their concern was that these individuals, disproportionately African American, would resume smoking and, if other studies are to be believed, would resume smoking non-menthol cigarettes, thereby increasing their risk of lung cancer compared to if they had continued smoking mentholated ones.

They are making a harm-reduction argument – banning menthol cigarettes might unintentionally increase lung cancer risk in those who switch. They are not recommending that menthol cigarettes not be banned, just that menthol smokers get more cessation support. They did not consider the possible further reduction in lung cancer risk for those who might switch to vaping. A recent review of the association of vaping with lung cancer found

“At present we lack unequivocal, epidemiological evidence of an association between e-cigarette use (either nicotine-based or other) and lung cancer. There exists, however, extensive data and excellent scientific rationale to suggest a significantly increased risk of lung cancer therewith.”

Given the long lag between inhalation and lung cancer, often 20 years or more, that data will not be available for some time. Now, with this new information and nuanced concern about an unintended consequence, I will ask again,

Now that you have the data, what do you, citizen-scientist, believe we should do?

[2] Menthol’s potential effects on nicotine dependence: a tobacco industry perspective Tobacco Control DOI: 10.1136/tc.2010.041970

[3] Epidemiology of menthol cigarette use Nicotine and Tobacco Research DOI:10.1080/14622203710001649696

Source: Smoking Quit Rates Among Menthol vs Non-Menthol Smokers: Implications Regarding a US Ban on the Sale of Menthol Cigarettes Journal of the National Cancer Institute DOI: 10.1093/jnci/djac070